Understanding Daily Scale Fluctuations

The scale is a dick huh? Well, that’s what you assume because you’re hyperemotional about it, so perhaps you’re the dick here. Didn’t think I’d turn the tables like that so early huh?

There’s a stigma about cardio causing muscle loss that sends chilling fear down a meathead’s spine. Maybe you can relate and get a bit anxious walking past a treadmill knowing that merely touching it could cause your precious biceps to wither away.

Ok perhaps that was a bit of an exaggeration, but let’s look at the evidence behind this subject and see if it’s a good idea to include for the sake of keeping our muscles thick and juicy.

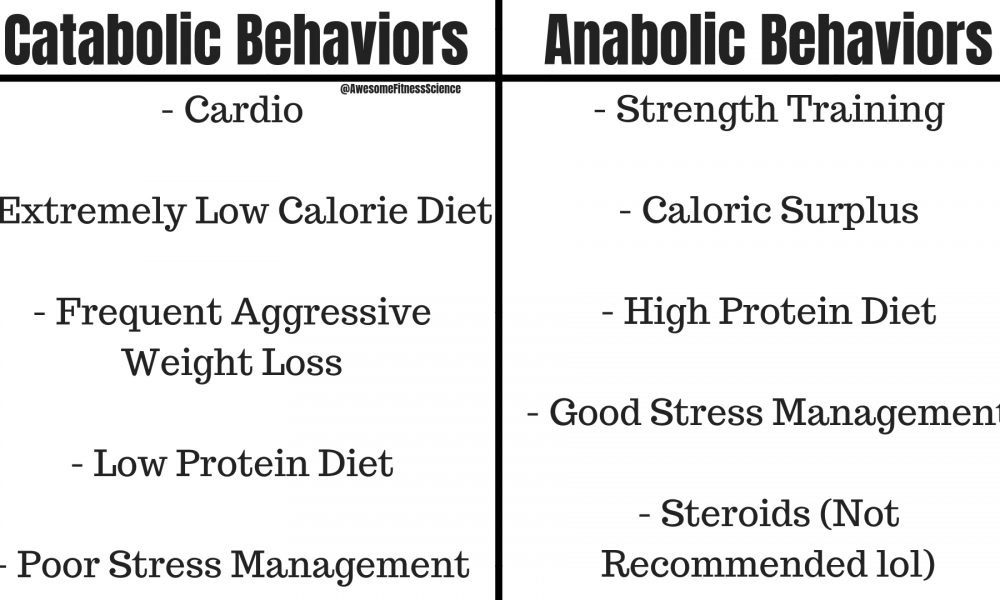

First, let’s look at how muscle is lost in the first place. Muscle is lost when your lifestyle is more catabolic than anabolic.

Catabolic basically tissue breakdown and anabolic tissue growth. In particular, your body will lose muscle if muscle breakdown exceeds the construction of new muscle tissue (also known as muscle protein synthesis MPS). A similar example is like going into debt. Debt happens when you spend more money than you make.

As you can see from the list above, cardio can be catabolic because it’s generally used to burn additional calories to create a deeper deficit. However, even cardio inherently causes muscle growth, but only in beginners (15).

To experience net muscle loss, you must live an extremely catabolic lifestyle as a whole while neglecting anabolic behaviors like strength training.

So long story short, cardio can contribute to muscle loss, but it’s unlikely.

So if you’re someone who strength trains consistently, including cardio isn’t going to cause muscle loss.

BUT! The story doesn’t end here. Don’t sigh a breath of relief quite yet my friend. Cardio probably won’t cause muscle loss, but it still has a dark side few people talk about.

You see research is definitively clear that formal cardio has an interference effect (1). By doing cardio, it interferes with potential strength, hypertrophy, and power adaptations. The molecular cascades and signaling pathways are different between strength training and cardio, some of which completely inhibit each other (16).

Simply put, cardio can reduce the amount of strength, muscle, and power you will gain from the strength training you do. Cardio also increases central nervous system fatigue much more and decrease your strength training performance (19).

This doesn’t mean you can’t make gains while including cardio, it just means you’ll probably make less than someone who focuses solely on strength training, especially for more advanced lifters (18).

The good news is research also shows us many ways to reduce the interference effect of cardio.

This study showed that doing a lesser amount or doing cardio less frequently will decrease the interference effect (1). So if you don’t do that much cardio, the interference effect probably isn’t that big of a deal.

To further decrease the interference effect, research has shown minimal to no interference if you do your cardio on a separate day from your strength training (2).

If that doesn’t work for your schedule, you can also reduce the interference effect by doing them on the same day so long as they’re at least 6 hours apart (3).

“Ok, but Calvin, I have a freaking life! I’m too busy to go to the gym for multiple sessions a day. I have to do my strength and cardio training in the same session bro!”

I hear you and fortunately, you can still reduce the interference effect even if you do them in the same session.

You simply need to do your cardio work after your strength work (4). Doing cardio before strength training can easily impair performance and reduce muscle fiber recruitment (5).

So when in doubt, do cardio after lifting.

As for the type of cardio to do to minimize the interference effect, read this article.

Now, I already know I’m going to get a bunch of cardio haters who claim all of this research is unnecessary because the obvious solution is to skip cardio altogether right?

Perhaps temporarily, but cardio can still be valuable to include at some point even if all you care about is strength and muscle.

You see cardio might have an immediate interference effect limiting your gains, but it might also be a necessary evil for your gains as well.

Studies show how important the aerobic system is in improving anaerobic performance (6,8,9,10).

There are 2 main reasons behind this:

Muscle capillarization seems to be the more important of the 2.

We have direct research on the elderly that low muscle capillarization limits how much muscle you can gain and even suppresses the body’s muscle growth signal (7,11,12). There’s no reason this doesn’t apply to young lifters, at least to a smaller extent.

Consequently, your aerobic base at a central or local level can limit the amount of strength training volume you tolerate or your work capacity across sets, especially as you start lifting bigger weights. Not to mention, good cardio means you won’t have to chicken out of a set early because your heart’s on the brink of explosion (6).

However, this is ironically much more relevant for males than females. Even though many women love cardio, female physiology is already quite aerobic based. Anyone who’s trained with the opposite sex knows this first hand. After a hard set, the chick will be ready to endure another set of squats within a minute while the dude will still be gasping for air.

Indeed research shows, women are not only extremely sensitive to capillarization enhancement, but that it barely limits their strength training capacity (6).

Thus, a good rule of thumb is that your cardio should be good enough to not cut most of your lifting sets short. If you’re unsure, you likely need cardio, especially if you’re a chubby guy. In cases like these, some cardio will do more good than harm.

Either Steady state or HIIT will be fine as far as intensity goes (13,14). However, the exact tool for cardio should likely be rotated. For example, doing low impact cycling which already has a low interference effect alongside strength training decreases hamstring fascicle length which can increase injury risk after 3 months (17).

So here are the key takeaways to wrap everything up like a neat Chipotle burrito.

As you can see, cardio is quite the 2-edged sword. It’s not the killer of muscle as people overexaggerate and it can be necessary for more gains long term. At the same time, it has an evil interference effect that you want no part of. Ultimately, whether to include cardio and exactly how much will come down to your individual profile, goals, and preference after weighing the pros and cons.

Robbins, Jennifer L, et al. “A Sex-Specific Relationship between Capillary Density and Anaerobic Threshold.” Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), American Physiological Society, Apr. 2009, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2698638/.

Verdijk LB;Snijders T;Holloway TM;VAN Kranenburg J;VAN Loon LJ; “Resistance Training Increases Skeletal Muscle Capillarization in Healthy Older Men.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27327032/.

Moro T;Brightwell CR;Phalen DE;McKenna CF;Lane SJ;Porter C;Volpi E;Rasmussen BB;Fry CS; “Low Skeletal Muscle Capillarization Limits Muscle Adaptation to Resistance Exercise Training in Older Adults.” Experimental Gerontology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31518665/.

Snijders, Tim, et al. “Muscle Fibre Capillarization Is a Critical Factor in Muscle Fibre Hypertrophy during Resistance Exercise Training in Older Men.” Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, John Wiley and Sons Inc., Apr. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5377411/.

Cocks M;Shaw CS;Shepherd SO;Fisher JP;Ranasinghe AM;Barker TA;Tipton KD;Wagenmakers AJ; “Sprint Interval and Endurance Training Are Equally Effective in Increasing Muscle Microvascular Density and ENOS Content in Sedentary Males.” The Journal of Physiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22946099/.

Beneke, R., et al. “Training for Skeletal Muscle Capillarization: a Janus-Faced Role of Exercise Intensity?” European Journal of Applied Physiology, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1 Jan. 1970, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-016-3419-6.

Mascher, H., et al. “Enhanced Rates of Muscle Protein Synthesis and Elevated MTOR Signalling Following Endurance Exercise in Human Subjects.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 19 Apr. 2011, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02274.x.

Baar, Keith. “Using Molecular Biology to Maximize Concurrent Training.” Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), Springer International Publishing, Nov. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4213370/.

Timmins RG;Shamim B;Tofari PJ;Hickey JT;Camera DM; “Differences in Lower Limb Strength and Structure After 12 Weeks of Resistance, Endurance, and Concurrent Training.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32209722/.

Petré, Henrik, et al. “Development of Maximal Dynamic Strength During Concurrent Resistance and Endurance Training in Untrained, Moderately Trained, and Trained Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), Springer International Publishing, May 2021, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8053170/.

Brandenberger KJ. “Downhill Running Impairs Activation and Strength of the Elbow Flexors.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30908371/.

Sign up for AwesomeFitnessScience Weekly. You’ll get juicy insider secrets, updates, and stories.

The scale is a dick huh? Well, that’s what you assume because you’re hyperemotional about it, so perhaps you’re the dick here. Didn’t think I’d turn the tables like that so early huh?

For decades, bodybuilders have advocated for the mind muscle connection which refers to aiming your focus towards the targeted muscle you’re training.

One of the biggest barriers to improving your health/fitness is social pressure. In fact, for many people, it’s the biggest thorn.