The Comprehensive Guide on How to Build Lean Muscle

We all get to the point where we desire to build slabs of lean eye-popping muscles.

Diet breaks and refeeds are overrated. I know I’ll offend lots of people and frankly, I don’t give a flying fairy about it.

I mean, I get it. They seem cool, different, and even magical. I used to be a diet break band wagon rider back when the famous Matador study came out in 2017 (which I’ll talk about later).

However, over the years, I’ve realized, new doesn’t mean better.

After a more critical look at the research and experimenting with clients, I hardly implement diet breaks and refeeds with clients. They’re both more overrated than potato salad. Can you find a rare time and place where potato salad can be decent? Sure, but most of the time it’s not worth your thought which is my point.

Anyways, let’s get into the diet break science before I start ranting too much about potato salad.

A diet break also called intermittent dieting (not to be mistaken with intermittent fasting) is a literal break in a diet. With a diet break, you stop dieting to spend time at maintenance. Generally speaking, a diet break is 1 week, but it can be longer. There’s no set rule for this.

The idea behind diet breaks is that dieting sucks and by eating more calories temporarily, you’re able to boost your metabolism, prevent metabolic adaptation, improve appetite hormones, reduce stress hormones, increase muscle retention, make it easier to diet, and speed up fat loss.

Sounds like the absolute dream right? Well, let’s look at the actual research and not merely what your favorite coaches post about the research.

To be clear, this article will be on diet breaks. Part 2 will be on refeeds which are like mini diet breaks.

Many diet break studies have promising conclusions, but people don’t realize that diet breaks take time away from dieting. If diet breaks intend to make us reach our fat loss goals better, the time taking the break has to be more meaningful than the alternative of simply continuing the diet.

The first diet break sort of study put obese men and women into 2 dieting groups (1). One group dieted on 530 calories continuously for 6 weeks. The other group dieted on the same calories for three 2-week periods separated by two 4-week blocks of higher calorie dieting. The diet break group technically didn’t go to maintenance so technically not an official diet break.

Both groups achieved the same weight loss and weight maintenance, but the continuous group got their results 8 weeks earlier while the diet break group spent an extra 8 weeks doing an easier diet.

Next is Wing and Jeffery’s study who had 3 groups of dieters dieting for 14 weeks (2). The control group dieted for 14 weeks straight. The short break group took a 2-week break every 3 weeks. The long break group took a 6-week break halfway through.

The conclusion read that all 3 groups lost the same weight, statistically speaking. However, there is more than meets the eye.

The continuous control group got those results after 14 weeks. The other 2 groups spent an extra month and a half to get similar results. In addition, the continuous group started at a lower body weight and still had effect sizes favoring them for weight loss.

While adherence data showed the diet break group had no problem getting back on track, total adherence was similar between groups, so the claim that diet breaks increase adherence is unsupported by this study. In addition, behavior metrics suffered in both the diet break groups. They struggled to get back to daily weighing, food tracking, and being conscious about food choices.

So whether, you’re following a diet that restricts food or a flexible diet where you track your macros, breaking routine can make it psychologically hard to get back on track especially at the cost of taking time away from losing more weight.

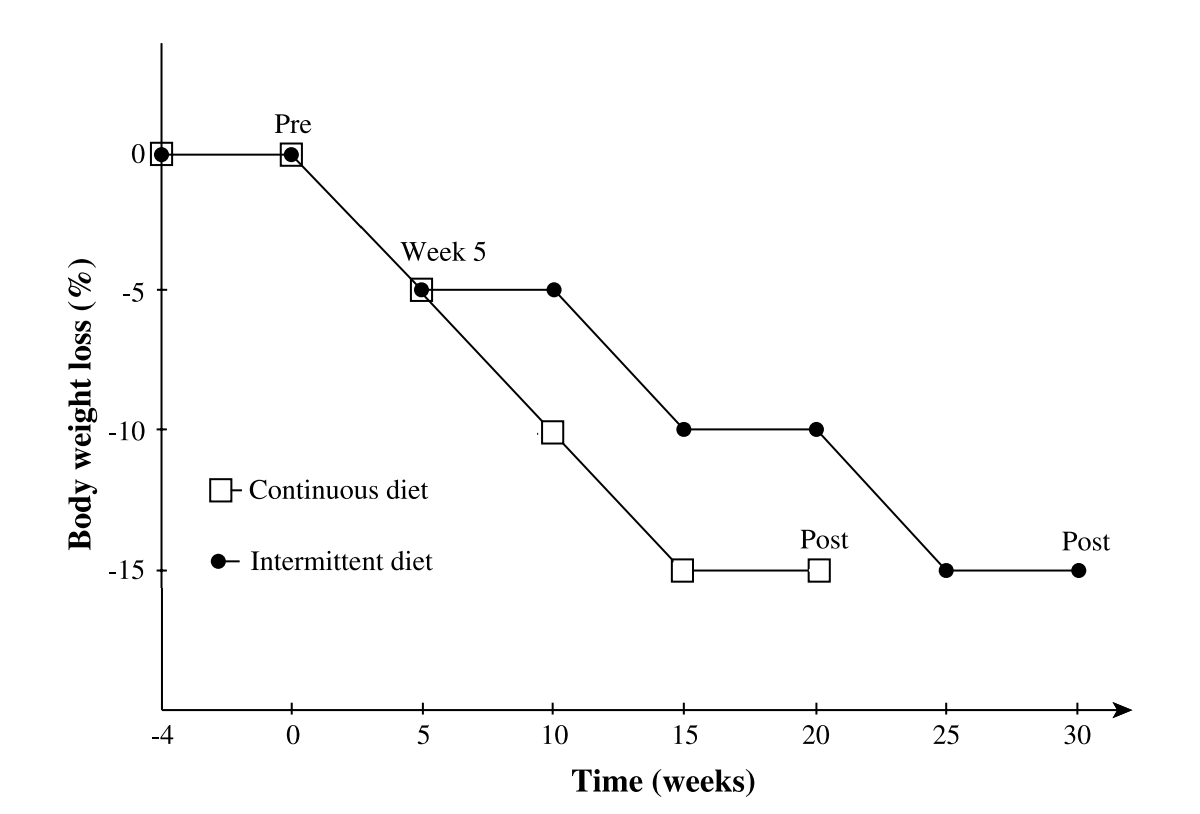

Then there’s Arguin et al 2013 which compared obese women doing continuous dieting or taking diet breaks (3). Both groups had the same deficit. The continuous group dieted for 15 weeks while the diet break group took a 5-week break at maintenance after week 5 and week 10.

Every 5-week block, both groups lost the same percentage of weight, but because the diet break group took 10 extra weeks at maintenance, it took them almost twice the amount of the time to reach the same total results. In practice, if these were leaner individuals, the continuous group could’ve spent an extra 10 weeks bulking once they got lean or kept losing more body fat if they needed to.

See the graph below. Look at week 5. While the diet break group stopped making progress, the continuous group kept going.

By the end of the study, there was no difference in metabolic rate, health markers, or adherence. In fact, despite starting at a clearly higher body weight, the diet break group had a trend of slightly more muscle loss. So taking a break doesn’t make you stick to your diet better, nor does it retain more muscle, and it definitely doesn’t boost your metabolism to enhance fat loss.

Then there’s Keogh et al 2014, which Is a prime reminder to always read the raw data of a study and not merely the author’s conclusion (4). In this study, the continuous group dieted for 8 weeks while the diet break group dieted for 1 week at a time followed by a 1-week break for 8 weeks. The diet break group essentially only spent 4 weeks in a deficit and statistically, the results were not significant between groups.

However, when looking at amount of weight lost, the continuous group lost twice as much fat after 8 weeks and after a 1 year follow up. In other words, you spend more time in the same deficit, you lose more fat, not to mention the behavioral benefits of practicing certain habits consistently.

Then we have the famous Matador study which was the first study to find an advantage to diet breaks (5). Unfortunately, a study being famous doesn’t make it a good study. This study had obese men diet either continuously for 16 weeks or diet for 2 weeks sandwiched with 2 week breaks for a total of 30 weeks.

The diet break group lost 4.3 kg more fat. They lost 50% more fat, but 50% more muscle. Nonetheless, the authors chalked this up to a metabolic advantage, but actual metabolic difference was merely 89 calories per day, nowhere near enough to explain the difference in weight loss.

In addition, the diet break group spent more time at maintenance which reverses any negative metabolic adaptations from dieting. The continuous group would experience the same thing if the researchers accounted for this.

But anyways, The Matador results don’t line up with their own data nor the results of every other study. A collection of studies (meta-analysis) found taking breaks has no advantage to continuous dieting, but wastes more time (6).

A more likely explanation for the Matador study was simply poor adherence. The study was done in obese men and the dropout rates were huge due to an astronomical 1000 calories deficit. No obese newbie dieter could sustain that for 16 weeks. In fact, the continuous dieting group lost the same fat until week 12 where they stopped eating their assigned deficit.

Technically, the diet breaks didn’t improve weight loss. You could say they improved adherence when using an extremely unrealistic method.

And even if the Matador study is somehow legit, would you really want to lose 50% more fat while sacrificing 50% more muscle and burning up 88% more time? The cost to benefit ratio is utterly poor even in the most questionable study.

Headland et al also conducted a pretty poorly controlled 1-year study comparing continuous dieting, diet breaks, and refeeds (7). The continuous dieting group lost the most fat at the end of the study and achieved greatest weight loss mid study despite starting at a pretty low body weight. The diet break and refeed group also had more dropouts because psychologically it’s hard to go back to dieting when you’ve halted the lifestyle.

There’s no consistency being built especially for dieting beginners. Clients tell me this all the time. They go off their plan and when trying to get back to dieting, they feel like they’re starting over. The mental obstacle later may not be worth the so-called mental relief of a diet break.

The more realistic a diet gets, the trend is clear, diet breaks aren’t worth the time.

Enter Siedler et al 2020, one of the best studies to date (8). They looked at continuous dieting vs diet breaks in strength trained females, a population that is much more adherent than obese populations. They used a realistic 25% deficit and matched for both protein intake and weekly exercise.

The Continuous dieting group dieted for 6 weeks while the diet break group took a 1-week break every 2 weeks.

Metabolic rate, weight loss, and body composition were the same between groups, except the diet break group had to dork around for an extra 2 weeks at maintenance to get the same results.

I had this article finished in early 2020. I was dismissive about diet breaks before it became cool. Many industry friends can confirm this. Now being skeptical of diet breaks is more common because we have even more compelling research confirming what I’ve been saying for years!

The new ICECAP trials is the largest (arguably most well conducted) diet break study to date (9). It’s also done in trained individuals. The continuous group dieted for 12 weeks while the diet break group took a 1-week break every 3 weeks.

Weight, muscle retention, fat loss, metabolic rate, and hormonal levels were the same between groups. These measures were taken after the continuous group stayed at maintenance at 3 weeks to match for the number of deficits and maintenance weeks between groups. So the continuous group got their results 3 weeks earlier.

Appetite and muscle endurance were slightly improved in the diet break group, but these measures were taken before the continuous group could hang out at maintenance (10).

Then Pannen et al published some follow up data in 2021 following 98 overweight and obese individuals (11). Self reported adherence was over twice as worse in the diet break group.

So a diet break is exactly what it sounds like. It’s a break. If you’re a trained lifter, you can get some dieting relief now or you can finish the diet sooner and get the relief later. Although for beginners, more consideration is needed because diet breaks also break up the behaviors that they’re trying to build.

Diet breaks are overrated. They don’t enhance the process of dieting, but rather pause and arguably interrupt the process of dieting. The fact that someone needs a diet break should indicate that the current diet is generally not sustainable. By taking a week off, it can feel like you’re mentally starting over just to return to the diet that wasn’t sustainable in the first place.

A better option if you’re struggling with your diet is to find ways to make your diet more sustainable. Once you’ve optimized your diet, there’s no real incentive to take a break.

It’s like having a good job with reasonable hours. Taking a break from it doesn’t make you more money. It forces you to take time off where you could’ve made more cash.

So you have to be ok with the tradeoff of literally taking a break. This generally only applies to long vacations.

The only other scenario I use diet breaks is with physique competitors who have to go on unsustainable calories for extended periods or females going through rough hormonal cycles, but most people dieting properly shouldn’t need a diet break during their dieting phase.

Especially if you have deadlines attached to your intended weight loss, you need to buckle down for some continuous dieting.

Part 2 of this article will hone in on refeeds and some of the other claims of non-linear dieting.

1. Rössner, S. “Intermittent vs Continuous VLCD Therapy in Obesity Treatment.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 27 Jan. 1998, www.nature.com/articles/0800563.

2. RW;, Wing. “Prescribed ‘Breaks’ as a Means to Disrupt Weight Control Efforts.” Obesity Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12582226/.

3. Arguin . “Short- and Long-Term Effects of Continuous versus Intermittent Restrictive Diet Approaches on Body Composition and the Metabolic Profile in Overweight and Obese Postmenopausal Women: a Pilot Study.” Menopause (New York, N.Y.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22735163/.

4. PM;, Keogh. “Effects of Intermittent Compared to Continuous Energy Restriction on Short-Term Weight Loss and Long-Term Weight Loss Maintenance.” Clinical Obesity, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25826770/.

5. Byrne. “Intermittent Energy Restriction Improves Weight Loss Efficiency in Obese Men: the MATADOR Study.” International Journal of Obesity (2005), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28925405/.

6. JB;, Headland. “Weight-Loss Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intermittent Energy Restriction Trials Lasting a Minimum of 6 Months.” Nutrients, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27338458/.

7. JB;, Headland. “Effect of Intermittent Compared to Continuous Energy Restriction on Weight Loss and Weight Maintenance after 12 Months in Healthy Overweight or Obese Adults.” International Journal of Obesity (2005), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30470804/.

8. “Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN) Conference and Expo: Daytona Beach, FL, USA. 11-12 September 2020.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7700811/.

9. Peos. “Continuous versus Intermittent Dieting for Fat Loss and Fat-Free Mass Retention in Resistance-Trained Adults: The ICECAP Trial.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33587549/.

10. Peos, Jackson J, et al. “A 1-Week Diet Break Improves Muscle Endurance during an Intermittent Dieting Regime in Adult Athletes: A Pre-Specified Secondary Analysis of the ICECAP Trial.” PloS One, Public Library of Science, 25 Feb. 2021, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7906362/.

11. Pannen. “Adherence and Dietary Composition during Intermittent vs. Continuous Calorie Restriction: Follow-Up Data from a Randomized Controlled Trial in Adults with Overweight or Obesity.” Nutrients, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33916366/.

Sign up for AwesomeFitnessScience Weekly. You’ll get juicy insider secrets, updates, and stories.

We all get to the point where we desire to build slabs of lean eye-popping muscles.

Many clueless Instagram influencers are big proponents of fasted exercise and love making extreme claims about it. Fortunately, you’ve stumbled onto this science-based article, where the truth will be revealed to you.

Hey ladies, you have so much going for you, but if I’m being honest, many of you avoid lifting weights to your detriment.