Dairy – A Healthy Choice That Idiots Don’t Realize

Dairy – A Healthy Choice That Idiots Don’t Realize Dairy is extremely misunderstood and often picked on by the vegan and paleo communities. Many people

You’ve probably heard the advice from meatheads to have protein immediately after your workout or else you’ll stay scrawny like a toothpick. You’ll see these bros chugging a premade shake as they finish their last rep or frantically preparing one in the locker room.

This opportunity to consume protein post workout is called the anabolic window, a term coined by bodybuilders.

However, the evidence-based fitness community has largely concluded the anabolic window is a myth. You’ll hear some of these PhD holding dorks say “just eat enough total protein, timing doesn’t matter.”

Shockingly, you’re about to see why the “uneducated” meatheads were actually closer to the truth of the anabolic window all along. Ironically, many evidence-based coaches don’t actually look at the scientific evidence. They simply look at other coaches who have a stack of degrees and blindly copy the same oversimplified conclusions.

Before I get into all the nitty gritty though, I wanted to remind you that regardless of the conclusion on protein timing, total protein intake will always be most important. Total daily protein intake correlates strongest for muscle growth up to 1.6g per kg daily (1,2).

So don’t even worry about perfecting post workout protein timing if you can’t even eat enough daily protein. Focus on that first. That being said, protein timing matters more than most coaches give it credit for.

We first must understand the muscle full effect. For those that don’t know, the muscle full effect is essentially the bodies limits on managing muscle growth. It limits it’s construction of new muscle proteins after about a dose of about 20-30 grams of protein (3). This is why many coaches agree that protein distribution matters, but ironically, not protein timing despite timing actually having more evidence as I’m about to describe.

After a workout, especially one involving strength training, you’re stimulating muscle protein turnover within the trained muscle. This means protein is being broken down and also constructed. The muscles become hypersensitive to amino acids and other nutrients because raw material is needed to repair the breakdown and to construct the stimulated growth.

Thus, post workout, your muscles delay and raise the ceiling of the muscle full effect regardless of the last meal. Eating within this period is essentially fueling the enhanced muscle building process (4,5).

But with all good things, this period has an ending point, thus an anabolic window of sorts must exist (3). If it didn’t, we could finish a leg workout today and eat protein next week expecting our legs to still maximally grow (or grow at all), but that’s obviously bologna.

Indeed, when looking at the elevated muscle protein synthesis response post workout, we can see the anabolic window is very much real. For untrained people or as I like to call them, newbies, the anabolic window can last as long as 72 hours even after an endurance workout (6).

Another study found after 8 sets of leg extensions, the anabolic window lasted up to 48 hours for beginners (7).

So as you can see, the anabolic window is so big for untrained lifters hence why it makes no difference for them whether they consume protein right after their workout or wait a few hours later (8).

As long as newbies eat enough protein daily, they’re essentially always eating inside their anabolic window and thus providing amino acids to the hypertrophy that their workouts stimulated.

From a muscle growth perspective, they probably don’t have to worry about post workout protein even after fasted training. However, in general, fasted training is not recommended due to hindered performance and potentially higher levels of protein breakdown (7,9,33,36).

It’s great that beginners don’t have to worry about their post workout protein especially if they didn’t train fasted but remember, you’re only a beginner for so long. Eventually, you get closer to your genetic ceiling and produce less net muscle growth per workout thus dwindling your anabolic window (10).

Training closer to failure and doing more volume also extends the anabolic window, but this effect isn’t huge within practical limits (11,12). You can only train so intensely and with so much volume within 1 session before it quickly hinders the rest of your training week.

So inevitably, your anabolic window along with it’s peak gets smaller and thus protein timing becomes more relevant.

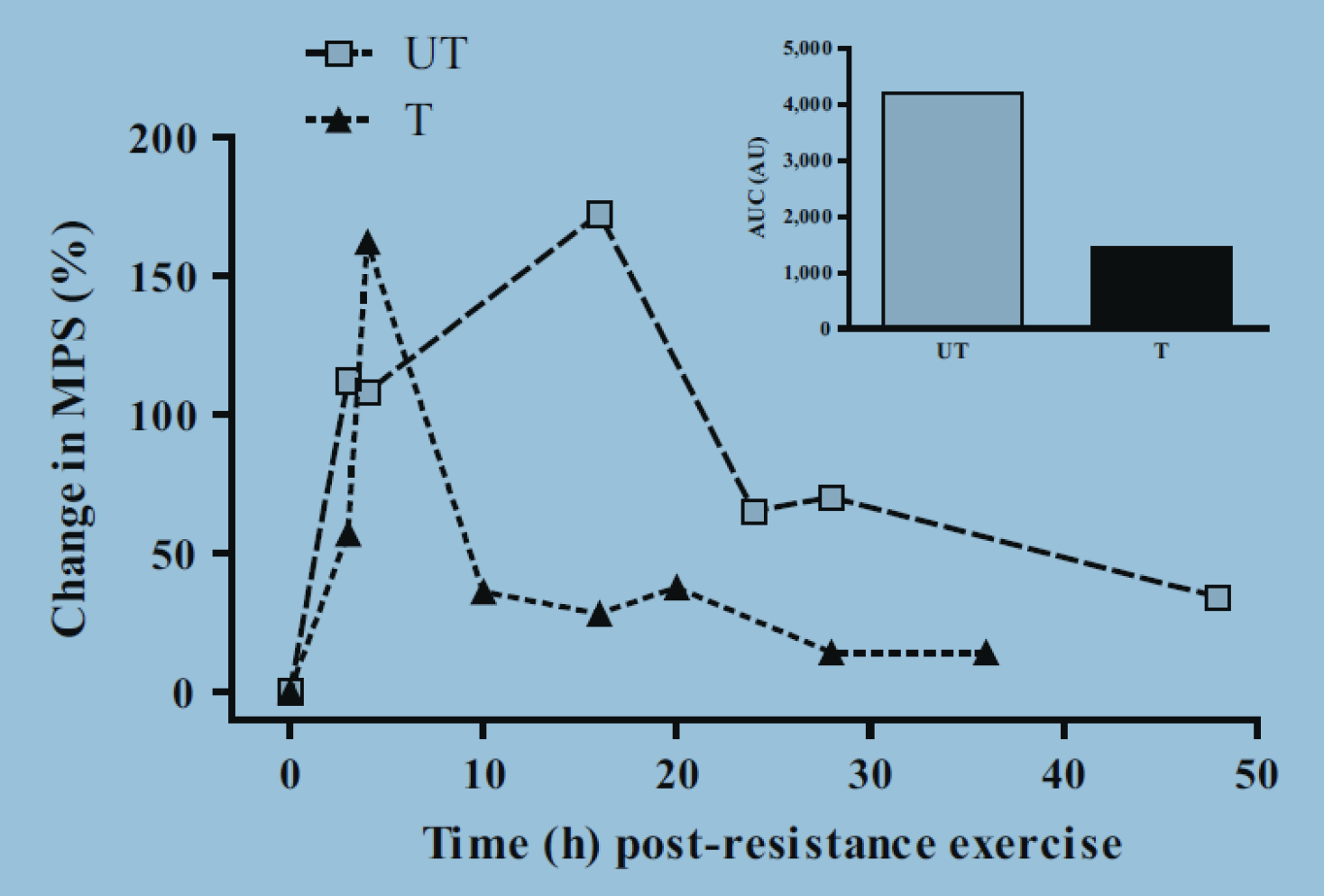

This can happen quite fast even if you don’t consider yourself an advanced lifter. Tang et al took complete newbies and had them train 1 leg for 20 sessions of increasing volume (13). Afterwards, they tested the anabolic window of both legs after a strength training session. One leg obviously resembled an untrained newbie, but the trained leg already had a shorter anabolic window after merely 20 workouts.

Relative to their respective levels, the untrained leg had an anabolic window past 28 hours post workout while the trained leg peaked at 4 hours and was near baseline at 16 hours. Within 28 hours the trained leg was completely back to baseline.

So the anabolic window easily applies to intermediate lifters as well as advanced lifters especially considering the literature’s version of advanced are usually college kids who’ve lifted for a couple of years. If you’ve been lifting longer than this, you better believe protein timing matters.

Indeed, Damas et al compiled a review of anabolic window research of untrained and trained lifters (14).

Untrained lifters generally have a smaller initial spike, but their muscle protein synthesis levels stay highly elevated for 24 hours before slightly declining for another 24 hours before the window closes after 2 days.

However, for trained lifters, they get a bigger initial spike, but this spike peaks within a few hours before sharply declining. By 10 hours, their anabolic window is barely elevated and completely closes off after 24 hours (statistically speaking).

In addition, Mori et al found trained lifters reached higher nitrogen balance (a measurement of protein balance) than untrained lifters by sandwiching their workout with protein (15). In addition, nitrogen balance is higher in a surplus than in a deficit because you’re able to build more muscle during a surplus (27,28).

So logically, it make sense to ensure a sufficient dose of protein, calories, and even micronutrients post workout if you’re a trained lifter especially if you’re bulking (16).

This will maximally stimulate muscle protein synthesis within the post workout meal.

A meta-analysis on the effects of protein timing was published in 2013 by some respectable names in the industry which concluded no effect on protein timing (1). The authors, Brad, Alan, and James are some of my favorite leaders in nutrition research, but their analysis isn’t the end all be all on this topic.

I get that a meta-analysis is usually a pretty strong piece of evidence, but unfortunately, many coaches read the summary and regurgitate the same conclusion without taking a closer look. If you read the entire analysis like a coach should, you’ll notice many things.

Despite lacking statistical power, many short-term studies are practically relevant because building muscle is already a slow process, especially for advanced lifters to which this topic most applies to, so you need to go through the research with finer comb.

Too many coaches blindly point to a bunch of studies and say, “see there’s no statistical effect,” but a more detailed look at the data does reveal protein timing matters. I’ve looked at nearly every study and the trends almost always favor protein timing to a considerable enough degree especially in trained lifters.

Even in untrained, you can see this. Hulmi et al looked at 3 different conditions, a carb post workout, a protein + carb post workout, and an only protein post workout group, all matching in calorie content (18).

The carb group actually ate more total protein and calories, but the other 2 groups gained more muscle with the protein only group gaining the most because they had the most protein post workout indicating timing made the biggest difference.

De Branco et al is in the same boat (19). No statistical difference in untrained lifters who barely gained any muscle due to a short time frame. But even with tiny effect sizes, you can see a clear effect of protein timing if you look at the fine print of a study. The non-protein timing group ate the same total protein and even ate more calories in a surplus, yet the protein timing group gained 33% more muscle.

Here’s a longer list of evidence that has accumulated since I was a baby that protein post workout matters especially in advanced lifters.

Keim et al (1997) was a metabolic ward study which is research done in a tightly controlled chamber (20). They took untrained women and had them either eat 70% of their calories in the am or in the pm. They all did cardio/strength training late morning which ended around noon.

The pm group lost more fat and retained more muscle indicating post workout protein is more important than pre workout protein because cough cough an anabolic window exists.

Burk et al (2009) supports this as well in untrained lifters (24). Protein post workout also gives you a higher protein balance than pre workout even after cardio in trained runners (21).

Kerksick et al (2006) took trained lifters and compared post workout carbs, protein, and protein with amino acids while matching for total calories and macros (22). The protein group who consumed whey with casein post workout gained much more muscle than the other groups while maintaining the same fat mass. In fact, the other groups didn’t even gain muscle.

Andersen et al (2005) which was also done in trained lifters had similar findings including strength benefits (23).

Jordan et al (2010) found higher nitrogen balance with protein post workout than pre workout in elderly men while controlling for total calorie intake (25).

Sharp et al (2017) compared post workout whey vs beef vs chicken vs carbs in trained lifters with all groups consuming more than sufficient protein (5). However, all protein groups lost more fat and gained more muscle especially the fast absorbing whey. The protein groups generally had better performance outcomes as well.

Lockwood et al (2017) compared carb timing to protein timing while matching for total macro intake in trained lifters (26). The carb timing group ended up eating more total calories and protein, but gained slightly less muscle while clearly accumulating more fat.

Kume et al (2020) compared pre vs post workout meal timing in untrained men. Despite the post workout group training fasted, muscle breakdown was more suppressed in this group when measured (33).

Churchward-Venne et al (2020) compared protein dosing post workout in trained endurance athletes after a cycling workout while matching for total protein intake (35). 45 grams of protein post workout outperformed 30 grams and 15 grams. More protein post workout had a better balance of whole body and muscle protein turnover despite this group eating the least reported total calories/protein. It shows post workout protein is important for endurance training, how much more so for strength training? You get the point.

Yeah bro, that anabolic window that all the bodybuilders have talked about since the beginning of time is a real thing and it’s quite relevant.

It’s not this 5-minute window where you have to chug a shake during your last rep, but within reason, the sooner, the better especially if one of the following applies to you:

So once you’ve completed a workout, you’ve essentially entered your anabolic window. How long this window lasts and the nuances of the peaks have already been discussed.

Because of the muscle full effect, you can only build so much muscle from an individual meal, so once your anabolic window starts, it generally makes sense to get 2 meals with some adequate time between meals before the window ends (34).

For full optimization, these 2 meals should be bigger than your meals outside of this window. For advanced lifters, it’s quite crucial that their first meal in the anabolic window be the most anabolic meal of the day due to their short lived anabolic window peak.

So this first anabolic meal should be the highest in calories and protein. At least 20-40 grams of protein for this post workout meal is the bare minimum to aim for depending on your size (30,31). The digestion speed of the protein choice matters less than simply getting enough protein, so whey, casein, or whole animal carcasses are all suitable post workout options (29).

This first anabolic meal should touch your mouth within 1-2 hours after your workout. If you’re highly trained, waiting longer post workout to finally cook protein is suboptimal.

The next meal within the anabolic window should come before the window starts to close, so for trained lifters, ideally within 12-16 hours of your workout to be safe.

This is why the idea of bulk and cut days isn’t wrong, but they’re not entirely right either. Don’t think in terms of days, think in terms of windows literally.

Assuming you’re an advanced lifter, if you train in the evening, your bulk day actually starts that night and ends the following afternoon. This means your dinner post workout should be your most anabolic meal and the breakfast during the following day can still be an anabolic meal that contributes significantly to muscle growth (32,33).

So anytime someone says the anabolic window isn’t real or relevant, send them over to this article either in a respectful or petty manner. I don’t really care; I simply want more people to be properly educated on the nuances of this topic.

Churchward-Venne, Tyler A, et al. “Dose-Response Effects of Dietary Protein on Muscle Protein Synthesis during Recovery from Endurance Exercise in Young Men: a Double-Blind Randomized Trial.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Oxford University Press, 1 Aug. 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7398777/.

Yasuda. “Breakfast before Resistance Exercise Lessens Urinary Markers of Muscle Protein Breakdown in Young Men: A Crossover Trial.” Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33418493/.

Sign up for AwesomeFitnessScience Weekly. You’ll get juicy insider secrets, updates, and stories.

Dairy – A Healthy Choice That Idiots Don’t Realize Dairy is extremely misunderstood and often picked on by the vegan and paleo communities. Many people

Strength training vs cardio is a flaming hot debate. However, it’s often misunderstood even when it comes to professionals.

Detoxing is the latest buzzword and everyone thinks they need to detox. However, nobody knows what they’re detoxing from, what detoxing accomplishes, and to how to go about it.