How Any Beginner Can Become a Macro Tracking Master

Tracking macros is the most lifechanging skill for your long-term health, fitness, and food flexibility

What if I told you about a strength training technique that pops your veins out, gets your arteries choked, and imposes a burning sensation hotter than Katy Perry wearing a sundress?

Ok, before your fantasies get carried away, I’m talking about blood flow restriction training (BFR). And while I guess BFR can be used to unleash your inner freak, it also has a myriad of relevant benefits to most lifters. Here’s everything you need to know about BFR.

BFR stands for blood flow restriction training. Some circles also call it occlusion or Kaatsu training. You perform strength training exercises with some sort of cuff or tourniquet to restrict blood flow.

BFR began in Japan in the 1960s with Dr. Yoshiaki Sato (1,2). Folklore has it that after praying on his knees for hours, he stood up, thinking, “Yo! My calves feel this burning sensation like a muscle pump.”

This moment was the catalyst to decades of BFR research and experimentation.

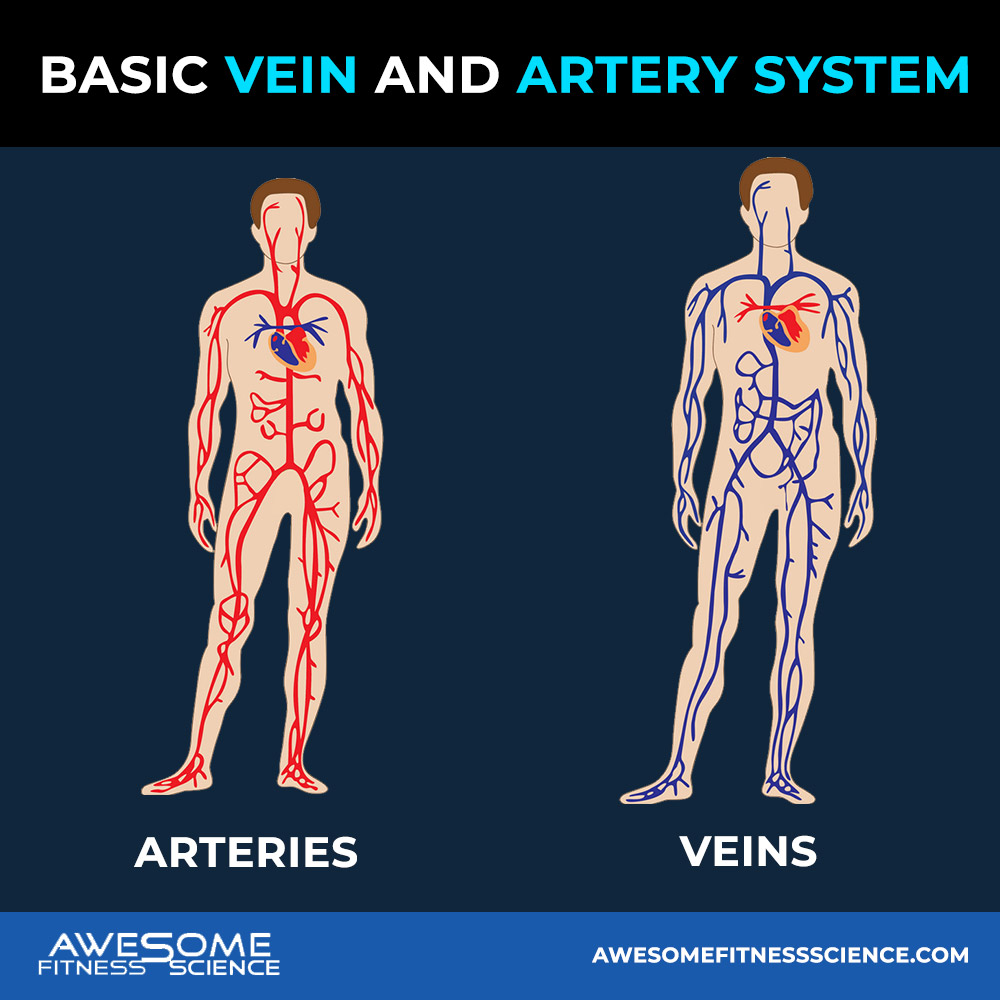

You have a system of veins and arteries running through your body. Your heart pumps blood into arteries which delivers nutrients to your muscles. Your veins connect with your arteries through capillaries and directs blood back into the heart.

Because your heart accelerates blood through your arteries faster than your veins can direct blood back, a cuff squeezing your muscle tissue together will inevitably trap more blood before it gets back.

This accumulates deoxygenated blood and metabolites which are waste products like lactic acid (3,4). This general process is also what meatheads call the pump or what nerdy meatheads call metabolic stress (5). Muscle contractions can achieve the same thing without using BFR cuffs, but at a slower rate alone.

So the combination of your limbs being suffocated by cuffs while your muscles lift weights creates an accelerated pump (4,6). This accomplishes 2 things:

I’ve written on this before, but here’s a summarized version.

Your muscles have motor units which are neurons that control and activate a group of muscles. Most type 1 fibers will activate first within any lifting set. As fatigue occurs and these type 1 fibers fatigue, your higher threshold motor units come in to keep the weight moving. With BFR, the additional metabolic stress fatigues the local muscle faster, allowing those type 2 muscle fibers to turn on sooner in the set (7). The fatigue also makes lighter weights feel heavier and gets you to those slow grinding reps needed for robust muscle growth sooner (8).

When The Undertaker choke slams his opponents, it looks wicked, but it’s staged. His opponents aren’t in any real danger. BFR is similar to that. Choking your muscles appears dangerous, but it’s in a controlled setting.

Plus, as I alluded to earlier, people don’t realize they are doing the same thing when lifting weights anyways without a cuff anyways. Your own muscles restrict blood flow as they produce force. This is why strength training briefly increases blood pressure, but always reduces it in the long term (9).

Indeed, research finds BFR is safe for your limbs and cardiovascular system (assuming proper implementation) in a variety of people including elderly populations (2,4,7,10,11,12).

So unless you’re pregnant, have high blood pressure, or have a history of vascular/cardiac issues, you’re safe to intelligently apply BFR (13).

BFR stimulates the tension needed for optimal muscle growth by making lighter weights feel heavier. Thus, even with loads as little as 20% of 1-RM, a set of BFR grows the same amount of muscle as a traditional set with optimal loads, assuming the proximity to failure is matched (2,4,7,14-20).

Since BFR fast tracks you to metabolite accumulation, your volume load performance is compromised (21,22). Combined with lower central nervous system activation (23), BFR produce less strength gains compared to traditional sets (24-31).

From a hypertrophy standpoint though, BFR may be unique in biasing type 1 muscle fiber growth thanks to the high rep nature and high levels of metabolic stress hindering type 2 muscle fiber recovery (22,32,33).

One study found no difference in type 1 muscle fiber growth between BFR and traditional sets, but did find BFR improved muscle endurance which is neat considering BFR reduces rep performance if matched for load/intensity (34).

In fact, BFR is pretty remarkable at improving vascular filtration, oxygen/nutrient delivery, and blood vessel count which improves endurance performance (35-39).

Furthermore, because BFR allows for the same total muscle growth per set with a lighter load, it’s an excellent tool when higher loads aren’t as tolerable like to reduce joint/connective tissue stress or after rehabbing from an injury (40,41,42).

BFR has a unique pain modulating effect which directs the stress towards your muscles. You generally feel less joint stress at the expense of your muscles burning painfully. Training quads or calves with BFR may be one of the most sadistic things you can do to yourself.

But this helps for joint friendly training in addition to adapting you to higher level of efforts/pain tolerance (43-47).

While joint stress is reduced, neuromuscular fatigue is still quite high with BFR. BFR imposes a particularly high level of muscle damage and muscle swelling when freshly introduced especially in novices (48,49).

However, once the repeated bout effect takes place, meaning once you get used to the heightened metabolic stress like stimulus, BFR has the same recovery levels as high load traditional strength training and likely better recovery than low load traditional strength training (50,51,52).

So BFR should be introduced in low volumes if you’re a beginner or haven’t done it in a certain muscle group in a while. After a few weeks, you can slowly ramp up the volume if needed.

While BFR cuffs can only be applied to limbs (forearm, upper arms, calves, and thighs), they can still be used to target any muscle using single joint or compound exercises.

The former is easy. If you want to train biceps, you apply the cuffs on your upper arm and do curls. But you can train some trunk muscles as well. For example, you can occlude your arms during the bench press and as the cuffs fatigue your triceps, your pecs will be forced to work harder (53,54).

The same phenomenon occurs with the glutes and squats (55).

But because BFR is typically done for higher reps with light load single joint exercises, they’re generally best done towards the end of the workout after your non-BFR work.

Many people recommend short rest periods with BFR for extra metabolic stress, but this is unnecessary as the pump itself isn’t what grows the muscle, but it merely opens the door earlier for mechanical tension to be applied to your muscles. So for better rep performance, longer rest periods may be desirable especially since BFR is pretty painful (56)

This is why taking the cuffs off between sets is ideal. You get the same muscle activation, muscle damage, but with a higher rep performance and less pain/discomfort (23,57,58,59). I personally just keep them on because I’m too lazy to take them off between sets.

Some people don’t feel the need to even do BFR until they experience an injury, and that’s fine if you want to keep your training simple, but that’s likely suboptimal. You should have periods of including some BFR to reduce average joint/connective stress across training weeks while reaping all it’s other benefits like increasing pain/effort tolerance.

In some cases, you may have to use BFR in perpetuity for some exercises like exercises you can’t tolerate much load due to severe injury or if you’re someone training at home with limited weights.

For what to use for occlusion, you can technically use anything from powerlifting knee wraps to torniquets, but BFR specific cuffs are best because they will have a quantifiable level of tightness that you can keep consistent between sets and between workouts. The exact cuff size or material doesn’t make a difference, so that’s up to your preference (64,65).

The 2 most common areas to apply the cuffs are the upper arm and thighs, although you can apply cuffs to your forearms and calves as well if you’re training those muscles.

The exact placement doesn’t really matter. I generally tell my clients to place it in the middle of the muscle.

You want it tight enough to stimulate a burning pump from your sets which should reduce the load you’re able to do compared to not having the cuff on (60). That being said, once it’s tight enough, there’s no benefit and only increasing risk/pain for going too tight (57,61).

Remember, BFR only works if you can allow the veins to still pool in some blood to the local muscle. Not to mention excessive tightness can cause you to pass out or end up in the hospital which is pretty counterproductive (62). After all, it is called blood flow restriction training not blood flow blocking training.

However, you can go a bit tighter for your thighs compared to your arms because the legs have more fat and don’t change in circumference as much when pumped.

In general, staying under a 7/10 on a self-assessment tightness scale should keep you safe (61,62,63). Yes, that’s a subjective scale, but there’s no practical way to objectively measure your arterial stiffness in the gym every workout. You’ll be fine as long as you’re not being an idiot. When in doubt, error on being too loose.

As I alluded to earlier, BFR improves muscular endurance, so consequently, it also improves cardiovascular capacity as well.

So although, BFR is popularized for strength training use, it can be used to achieve cardio adaptations in a shorter period of time (66,67,68). It’s an underutilized aspect of BFR and something I’ve found success experimenting with.

Cuff application and programming for cardio with BFR is essentially the same as strength training.

Now here are some cute bullet points to summarize this kinky training technique.

1. Sato, Y. “The History and Future of Kaatsu Training.” International Journal of KAATSU Training Research, Japan Kaatsu Training Society, 18 July 2008, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/ijktr/1/1/1_1_1/_article.

2. Patterson, Stephen D, et al. “Blood Flow Restriction Exercise: Considerations of Methodology, Application, and Safety.” Frontiers in Physiology, Frontiers Media S.A., 15 May 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6530612/?fbclid=IwAR3xsQmWfOERSyX6AcViiTkGNDktJC3AXvUClnG3tUSfRxuZTb46aIcFIOU.

3. Drouin . “Fatigue-Independent Alterations in Muscle Activation and Effort Perception during Forearm Exercise: Role of Local Oxygen Delivery.” Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31070953/.

4. Lorenz . “Blood Flow Restriction Training.” Journal of Athletic Training, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33481010/.

5. de Freitas, Marcelo Conrado, et al. “Role of Metabolic Stress for Enhancing Muscle Adaptations: Practical Applications.” World Journal of Methodology, Baishideng Publishing Group Inc, 26 June 2017, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5489423/.

6. Fatela . “Blood Flow Restriction Alters Motor Unit Behavior during Resistance Exercise.” International Journal of Sports Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31291650/.

7. Mechanic, 1The Human Performance. “Blood Flow Restriction Training and the Physique Athlete: A … : Strength & Conditioning Journal.” LWW, https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Fulltext/2020/10000/Blood_Flow_Restriction_Training_and_the_Physique.4.aspx.

8. (PDF) Acute Impact of Blood Flow Restriction on Strength … https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349428243_Acute_impact_of_blood_flow_restriction_on_strength-endurance_performance_during_the_bench_press_exercise.

9. Cornelissen, Véronique A., et al. “Impact of Resistance Training on Blood Pressure and Other Cardiovascular Risk Factors.” Hypertension, 6 Sept. 2011, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/hypertensionaha.111.177071.

10. Loenneke, J. P., et al. “Potential Safety Issues with Blood Flow Restriction Training.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 16 Mar. 2011, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01290.x.

11. da Cunha Nascimento, Dahan, et al. “Potential Implications of Blood Flow Restriction Exercise on Vascular Health: A Brief Review.” Sports Medicine, Springer International Publishing, 26 Sept. 2019, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-019-01196-5.

12. MD;, Poton. “Hemodynamic Responses during Lower-Limb Resistance Exercise with Blood Flow Restriction in Healthy Subjects.” The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24998617/.

13. “(PDF) Safety Considerations with Blood Flow Restricted Resistance Training.” ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293767736_SAFETY_CONSIDERATIONS_WITH_BLOOD_FLOW_RESTRICTED_RESISTANCE_TRAINING.

14. Lixandrão, Manoel E., et al. “Magnitude of Muscle Strength and Mass Adaptations between High-Load Resistance Training versus Low-Load Resistance Training Associated with Blood-Flow Restriction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sports Medicine, Springer International Publishing, 17 Oct. 2017, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-017-0795-y?wt_mc=alerts.TOCjournals.

15. Takarada, Yudai, et al. “Effects of Resistance Exercise Combined with Moderate Vascular Occlusion on Muscular Function in Humans.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 1 June 2000, https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2097.

16. Kubo . “Effects of Low-Load Resistance Training with Vascular Occlusion on the Mechanical Properties of Muscle and Tendon.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16871002/.

17. Thiebaud, Robert S., et al. “The Effects of Elastic Band Resistance Training Combined with Blood Flow Restriction on Strength, Total Bone‐Free Lean Body Mass and Muscle Thickness in Postmenopausal Women.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 3 Apr. 2013, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cpf.12033.

18. Lowery, Ryan P., et al. “Practical Blood Flow Restriction Training Increases Muscle Hypertrophy during a Periodized Resistance Training Programme.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 4 Nov. 2013, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cpf.12099.

19. Ramis . “Effects of Traditional and Vascular Restricted Strength Training Program with Equalized Volume on Isometric and Dynamic Strength, Muscle Thickness, Electromyographic Activity, and Endothelial Function Adaptations in Young Adults.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30063556/.

20. Biazon. “The Association between Muscle Deoxygenation and Muscle Hypertrophy to Blood Flow Restricted Training Performed at High and Low Loads.” Frontiers in Physiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31057426/.

21. J;, Wernbom. “Acute Effects of Blood Flow Restriction on Muscle Activity and Endurance during Fatiguing Dynamic Knee Extensions at Low Load.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19826283/.

22. Moore, Daniel R., et al. “Neuromuscular Adaptations in Human Muscle Following Low Intensity Resistance Training with Vascular Occlusion.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, Springer-Verlag, 17 June 2004, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-004-1072-y.

23. Wernbom, Mathias, and Per Aagaard. “Muscle Fibre Activation and Fatigue with Low‐Load Blood Flow Restricted Resistance Exercise-an Integrative Physiology Review.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 18 June 2019, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/apha.13302.

24. 1Laboratory of Neuromuscular Adaptations to Strength Training. “Comparisons between Low-Intensity Resistance Training with… : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research.” LWW, https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Fulltext/2015/04000/Comparisons_Between_Low_Intensity_Resistance.29.aspx.

25. Martín-Hernández, J., et al. “Muscular Adaptations after Two Different Volumes of Blood Flow‐Restricted Training.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 27 Dec. 2012, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/sms.12036.

26. MG;, Karabulut. “The Effects of Low-Intensity Resistance Training with Vascular Restriction on Leg Muscle Strength in Older Men.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19760431/.

27. Yasuda . “Combined Effects of Low-Intensity Blood Flow Restriction Training and High-Intensity Resistance Training on Muscle Strength and Size.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21360203/.

28. Ellefsen, Stian, et al. “Blood Flow-Restricted Strength Training Displays High Functional and Biological Efficacy in Women: A within-Subject Comparison with High-Load Strength Training.” American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 1 Oct. 2015, https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpregu.00497.2014.

29. Lixandrão, Manoel E., et al. “Effects of Exercise Intensity and Occlusion Pressure after 12 Weeks of Resistance Training with Blood-Flow Restriction.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1 Sept. 2015, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-015-3253-2.

30. Scott, Brendan R., et al. “Blood Flow Restricted Exercise for Athletes: A Review of Available Evidence.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, Elsevier, 9 May 2015, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1440244015000961.

31. Summer B. Cook, Brendan R. Scott. “Neuromuscular Adaptations to Low-Load Blood Flow Restricted Resistance Training.” Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 1 Mar. 2018, https://www.jssm.org/hfabst.php?id=jssm-17-66.xml.

32. Bjørnsen T;Wernbom M;Kirketeig A;Paulsen G;Samnøy L;Bækken L;Cameron-Smith D;Berntsen S;Raastad T; “Type 1 Muscle Fiber Hypertrophy after Blood Flow-Restricted Training in Powerlifters.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30188363/.

33. Bjørnsen, Thomas, et al. “High-Frequency Blood Flow-Restricted Resistance Exercise Results in Acute and Prolonged Cellular Stress More Pronounced in Type I than in Type II Fibers.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 11 Aug. 2021, https://journals.physiology.org/doi/abs/10.1152/japplphysiol.00115.2020.

34. Pignanell. “Low-Load Resistance Training to Task Failure with and without Blood Flow Restriction: Muscular Functional and Structural Adaptations.” American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31823670/.

35. Larkin, Kelly A, et al. “Blood Flow Restriction Enhances Post-Resistance Exercise Angiogenic Gene Expression.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Nov. 2012, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3633075/.

36. K;, Kacin A;Strazar. “Frequent Low-Load Ischemic Resistance Exercise to Failure Enhances Muscle Oxygen Delivery and Endurance Capacity.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21385216/.

37. Sumide . “Effect of Resistance Exercise Training Combined with Relatively Low Vascular Occlusion.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18083635/.

38. BC;, Manini. “Blood Flow Restricted Exercise and Skeletal Muscle Health.” Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19305199/.

39. Ferguson. “The Acute Angiogenic Signalling Response to Low-Load Resistance Exercise with Blood Flow Restriction.” European Journal of Sport Science, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29343183/.

40. Loenneke. “Blood Flow Restriction: Rationale for Improving Bone.” Medical Hypotheses, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22305335/.

41. Centner. “Low-Load Blood Flow Restriction Training Induces Similar Morphological and Mechanical Achilles Tendon Adaptations Compared with High-Load Resistance Training.” Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31725362/.

42. Kubo . “Effects of Low-Load Resistance Training with Vascular Occlusion on the Mechanical Properties of Muscle and Tendon.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16871002/.

43. JL;, Giles. “Quadriceps Strengthening with and without Blood Flow Restriction in the Treatment of Patellofemoral Pain: A Double-Blind Randomised Trial.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28500081/.

44. Hughes, Luke, et al. “Comparing the Effectiveness of Blood Flow Restriction and Traditional Heavy Load Resistance Training in the Post-Surgery Rehabilitation of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Patients: A UK National Health Service Randomised Controlled Trial.” Sports Medicine, Springer International Publishing, 12 July 2019, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs40279-019-01137-2.

45. Hughes . “Examination of the Comfort and Pain Experienced with Blood Flow Restriction Training during Post-Surgery Rehabilitation of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Patients: A UK National Health Service Trial.” Physical Therapy in Sport : Official Journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31288213/.

46. Luke Hughes and Stephen David Patterson, et al. “The Effect of Blood Flow Restriction Exercise on Exercise-Induced Hypoalgesia and Endogenous Opioid and Endocannabinoid Mechanisms of Pain Modulation.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 10 Apr. 2020, https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.00768.2019.

47. G;, Korakakis. “Low Load Resistance Training with Blood Flow Restriction Decreases Anterior Knee Pain More than Resistance Training Alone. A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial.” Physical Therapy in Sport : Official Journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30268966/.

48. Wernbom, Mathias, et al. “Commentary: Can Blood Flow Restricted Exercise Cause Muscle Damage? Commentary on Blood Flow Restriction Exercise: Considerations of Methodology, Application, and Safety.” Frontiers, Frontiers, 1 Jan. 1AD, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2020.00243/full.

49. Bjørnsen, Thomas, et al. “Frequent Blood Flow Restricted Training Not to Failure and to Failure Induces Similar Gains in Myonuclei and Muscle Mass.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 7 May 2021, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/sms.13952.

50. Biazon . “The Association between Muscle Deoxygenation and Muscle Hypertrophy to Blood Flow Restricted Training Performed at High and Low Loads.” Frontiers in Physiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31057426/.

51. Mendonca, Goncalo V., et al. “Muscle Fatigue in Response to Low-Load Blood Flow-Restricted Elbow-Flexion Exercise: Are There Any Sex Differences?” European Journal of Applied Physiology, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 13 July 2018, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-018-3940-x.

52. Additional informationFundingThis work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo [grant number 2013/21218-4. “Muscle Damage Responses to Resistance Exercise Performed with High-Load versus Low-Load Associated with Partial Blood Flow Restriction in Young Women.” Taylor & Francis, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17461391.2019.1614680.

53. Yasuda . “Effects of Low-Intensity Bench Press Training with Restricted Arm Muscle Blood Flow on Chest Muscle Hypertrophy: A Pilot Study.” Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20618358/.

54. Yasuda, T., et al. “Electromyographic Responses of Arm and Chest Muscle during Bench Press Exercise with and without Kaatsu.” International Journal of KAATSU Training Research, Japan Kaatsu Training Society, 22 May 2008, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/ijktr/2/1/2_1_15/_article.

55. Abe, Takashi, et al. “Exercise Intensity and Muscle Hypertrophy in Blood Flow–Restricted Limbs and Non‐Restricted Muscles: A Brief Review.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 10 Apr. 2012, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1475-097X.2012.01126.x.

56. G, Jones, et al. “An Investigation into the Effect of Blood Flow Restriction on Pain and Muscular Endurance in Healthy Human Participants.” Journal of Physical Medicine, Scholars.Direct, 7 Feb. 2018, https://scholars.direct/Articles/physical-medicine/jpm-1-001.php?jid=physical-medicine.

57. 1School of Human Movement and Nutrition Sciences. “Similar Morphological and Functional Training Adaptations… : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research.” LWW, https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Abstract/2021/07000/Similar_Morphological_and_Functional_Training.2.aspx (57).

58. “Does a Resistance Exercise Session with Continuous or Intermittent Blood Flow Restriction Promote Muscle Damage and Increase Oxidative Stress?” Taylor & Francis, https://shapeamerica.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02640414.2017.1283430#.YNZzNBNKiJk.

59. Gabriel R. Neto, Jefferson S. Novaes. “Acute Effects of Resistance Exercise with Continuous and Intermittent Blood Flow Restriction on Hemodynamic Measurements and Perceived Exertion – Gabriel R. Neto, Jefferson S. Novaes, Verônica P. Salerno, Michel M. Gonçalves, Bruna K. L. Piazera, Thais Rodrigues-Rodrigues, Maria S. Cirilo-Sousa, 2017.” SAGE Journals, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0031512516677900.

60. Jessee, Matthew B., et al. “Muscle Adaptations to High-Load Training and Very Low-Load Training with and without Blood Flow Restriction.” Frontiers, Frontiers, 1 Jan. 1AD, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.01448/full.

61. Bell . “The Perceived Tightness Scale Does Not Provide Reliable Estimates of Blood Flow Restriction Pressure.” Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31553951/.

62. Loenneke, Jeremy P, et al. “Blood Flow Restriction Pressure Recommendations: A Tale of Two Cuffs.” Frontiers in Physiology, Frontiers Media S.A., 10 Sept. 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3767914/.

63. Lowery, Ryan P., et al. “Practical Blood Flow Restriction Training Increases Muscle Hypertrophy during a Periodized Resistance Training Programme.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 4 Nov. 2013, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cpf.12099.

64. 1School of Physical Education and Sport. “The Effect of Cuff Width on Muscle Adaptations after Blood… : Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise.” LWW, https://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Fulltext/2016/05000/The_Effect_of_Cuff_Width_on_Muscle_Adaptations.20.aspx.

65. Buckner . “Influence of Cuff Material on Blood Flow Restriction Stimulus in the Upper Body.” The Journal of Physiological Sciences : JPS, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27194224/.

66. Formiga, Magno F, et al. “Effect of Aerobic Exercise Training with and without Blood Flow Restriction on Aerobic Capacity in Healthy Young Adults: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, Sports Physical Therapy Section, Apr. 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7134358/.

67. Abe. “Effects of Low-Intensity Cycle Training with Restricted Leg Blood Flow on Thigh Muscle Volume and VO2MAX in Young Men.” Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24149640/.

68. Define_me, https://www.jsams.org/article/S1440-2440(19)30568-7/fulltext.

Grab my free Stupid Simple Scroll to Mastering Hypertrophy

Tracking macros is the most lifechanging skill for your long-term health, fitness, and food flexibility

Eating at night isn’t the reason you’re packing on the squishy pounds. In fact, carbs at night may be the little-known strategy towards your fittest physique.

You ready to go from a mere peasant who can’t stop eating to a satiated almighty weight loss emperor?