How to Master Intuitive Eating

In this article, I only talk about how to master intuitive eating. I went over the pros and cons of it in a previous article, so read that one first.

Hunger and cravings are the 2 reigning forces that stand in your way of conquering weight loss once and for all.

If you can defeat these 2 obstacles, not only is continual weight loss guaranteed, but sustaining your lean body for years to come becomes effortless. That sounds great, but it’s definitely not easy or else we’d all be lean machines who effortlessly stay full and resist donuts.

So get prepared for battle my friend. In today’s article, we’ll go over how to defeat hunger. Part 2 will tackle how to defeat cravings.

Strap in my friend. It’s a long one, but you will have the most powerful understanding of dominating hunger a human can attain. You’ll go from a mere peasant who can’t stop eating to a satiated almighty weight loss emperor on their rightful throne.

Appetite is your overall system that influences your desire to eat (1). It encompasses both your hunger and cravings which can have many overlapping, yet different nuances.

Hunger is basically our biological drive to eat, partially because we have to or else, you know, you eventually die.

More specifically, hunger is a feeling stimulated by your brain that drives you to find food and eat. A multitude of physical, psychological, and environmental cues stimulate hunger, but nonetheless fighting hunger is key to weight loss. Doing so means filling the void in your stomach along with pleasing your brain’s desire for food reward (4).

However, if hunger is left unattended, negative feelings skyrocket which is why we get hangry as many people describe it (2).

To appease this hangry feeling, we must get satiated.

The inverse of hunger is satiety which is simply a fancy word for fullness. As satiety increases, hunger decreases which slowly brings you to a state of satiation which is the feeling of fullness that warrants the end of a meal (3).

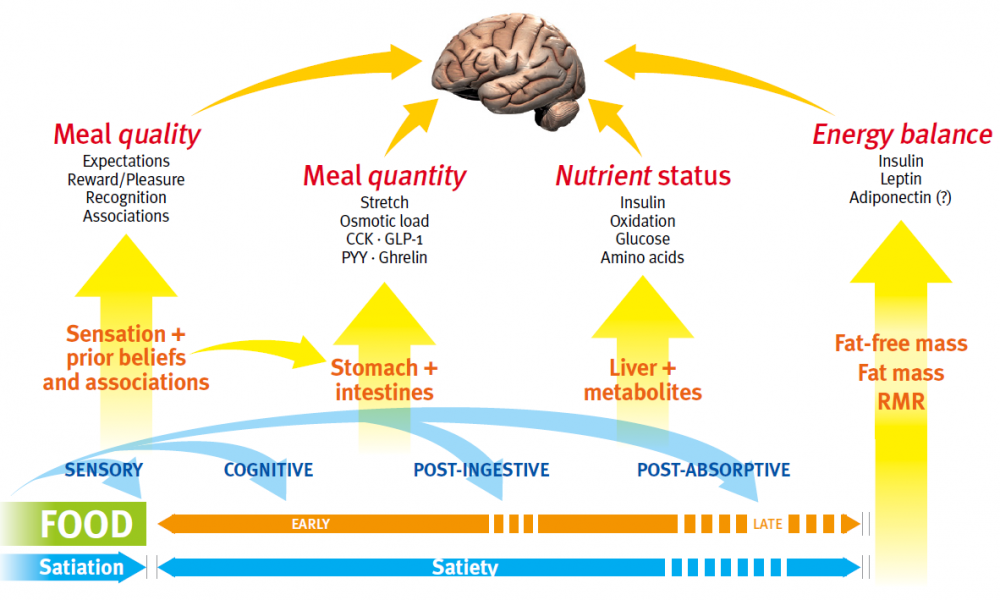

Obviously, eating essentially bridges the gap between hunger and satiation. This triggers a complex satiety cascade which involves many processes in getting you full (3). It’s important to roughly understand this to learn why some strategies later impact different pathways.

The satiety cascade is as follows:

If you’ve been following me for long enough, you’ll know that energy aka calories are like, ridiculously important. They’re the unit of energy in nutrition and undeniably dictate long term weight change no matter how many internet clowns like to say calories don’t matter.

But as it relates to hunger, eating calories obviously satiate our appetite. That’s a no brainer, but what people don’t realize is this effect is stronger than body composition’s effect on hunger.

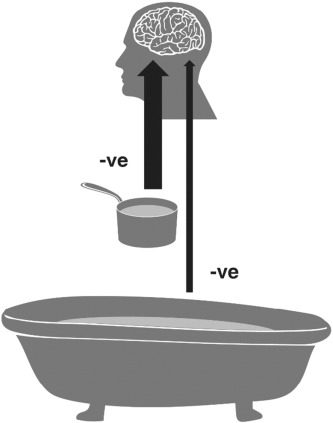

Let me explain using the sauce pan and bathtub phenomenon of hunger (4).

The sauce pan represents food in your gut while the bathtub represents your total energy stores.

The arrow size represents the signal for satiety. As you can see, energy in your stomach fills you up more than simply having a lot of energy stored. As the saucepan fills up, it takes a while for the contents of the saucepan to be stored in the bathtub which will impact your underlying hunger/satiety as well. Let’s get nuanced my friend.

Leptin is a key appetite suppressing hormone produced by your fat stores (5,6). The more fat you have, the more leptin you produce. From a human survival perspective it makes sense. Being fat is disadvantageous in life, especially if you have to run away from wildlife and slay dragons for food. Thus gaining more body fat downregulates your appetite so you don’t get fatter, which ensures a higher rate of survival.

However, we live in the 21st century where the risk of being eaten by dinosaurs and dragons are non-existent, so this mechanism is less relevant. In addition, our modern world has engineered food so tasty, we end up eating far past our hunger/fullness signals and gain lots of fat over time (7).

In fact, at some point, you can get so fat, you end up producing less leptin because your hormones get dysregulated, fullness signals get trashed, and leptin resistance occurs (8,9).

So fat mass impacts hunger differently depending on what body fat percentage you’re at. This is one of the reasons obese people struggle to stay satisfied with food, but if they lose enough fat, their leptin gets restored and they feel more satiated carrying less fat mass.

However, for most people starting from an average body fat percentage, losing more fat means less leptin and more underlying hunger as you continue to lean out. You can’t hack this. You have to accept it and learn to manage your hunger better with lifestyle choices as I’ll describe later.

Muscle’s impact on hunger is also quite nuanced. More muscle means more hunger partly due to increased energy expenditure. This also makes sense from a survival perspective (10). Muscle mass is advantageous for strangling bears and withstanding centaur attacks, so the body will be driven to eat more to maintain it cause muscle increases your energy expenditure.

In fact, muscle mass correlates stronger with hunger than fat mass does (8,9). This is why it’s common for people who start lifting to gain bigger appetites. It’s not a coincidence.

So more muscle means more hunger, but guess what? Less muscle also means more hunger too (10,167,168). The body hates losing muscle which will exasperate metabolic adaptations during dieting, one of which is increasing hunger.

So long story short, losing and gaining muscle increases underlying appetite. You might as well gain muscle because muscle mass burns more calories to offset appetite, not to mention more muscle makes you look more like a superhero whereas less muscle mass makes you look wimpy.

As described by the saucepan vs bathtub model, your food intake will strongly satiate your brain while the underlying hunger from your stored energy has less of an effect. The bathtub is also quite hard to hack because underlying leptin/hunger regulations are dictated by total body composition not recent energy intake (11,12). So the cumulative energy balance matters not the acute.

How much you ate yesterday has little impact on how hungry you’ll be the next day. For example, after lean men and women ate a 75% deficit for a day, free eating conditions only increased calorie consumption by 7% the following day and had no effect the following day (13). Hunger hormones were also unaffected.

In another 2 studies, alternating the same massive deficit didn’t impact hunger or activity on alternating free eating days and even suppressed appetite on deficit days, although this was done in obese subjects (14,15).

So sleep essentially resets your base appetite back to what your current body composition dictates (19).

This is why apart from contest prep, refeeds are a poor hunger management strategy when dieting. Stopping your diet to temporarily eat more at maintenance can’t trick your body into producing more leptin long term. Remember, leptin isn’t dictated by energy intake, but total fat mass (16). In fact, leptin adapts within 12 hours (16,17).

You have to actually gain the fat back to increase leptin long term. As a matter of fact, spiking calories up especially into a surplus can even increase appetite which is counterproductive (18). Essentially, your base appetite is set at your current body composition. If you’re struggling to maintain that body composition, you have to learn how to intelligently fulfill the hunger level that your appetite brings, which we’ll go over more strategies later.

Exercise is a potent appetite suppressant (20,21,22). Strength training in particular is the ultimate training for weight loss as it’s more appetite suppressing than cardio (23,24). Psychologically, people also feel they deserve to reward themselves with more food after cardio (26).

So pretty much anything with higher intensities is better and more appetite suppressing (25). This makes sense as intense training fires up your nervous system into fight or flight mode along with drawing your focus towards hard muscle contractions.

If you find yourself hungry during a workout, you’re likely not training hard enough. Hard training has you focused on lifting, not going into a drive-thru.

In general, though, exercise as a whole suppresses appetite. Ever get hungry and went for a simple walk instead? You’ll notice the hunger quickly fades mid walk.

However, more physical activity means more energy expenditure which as we discussed earlier is a mechanism to increase hunger in the body.

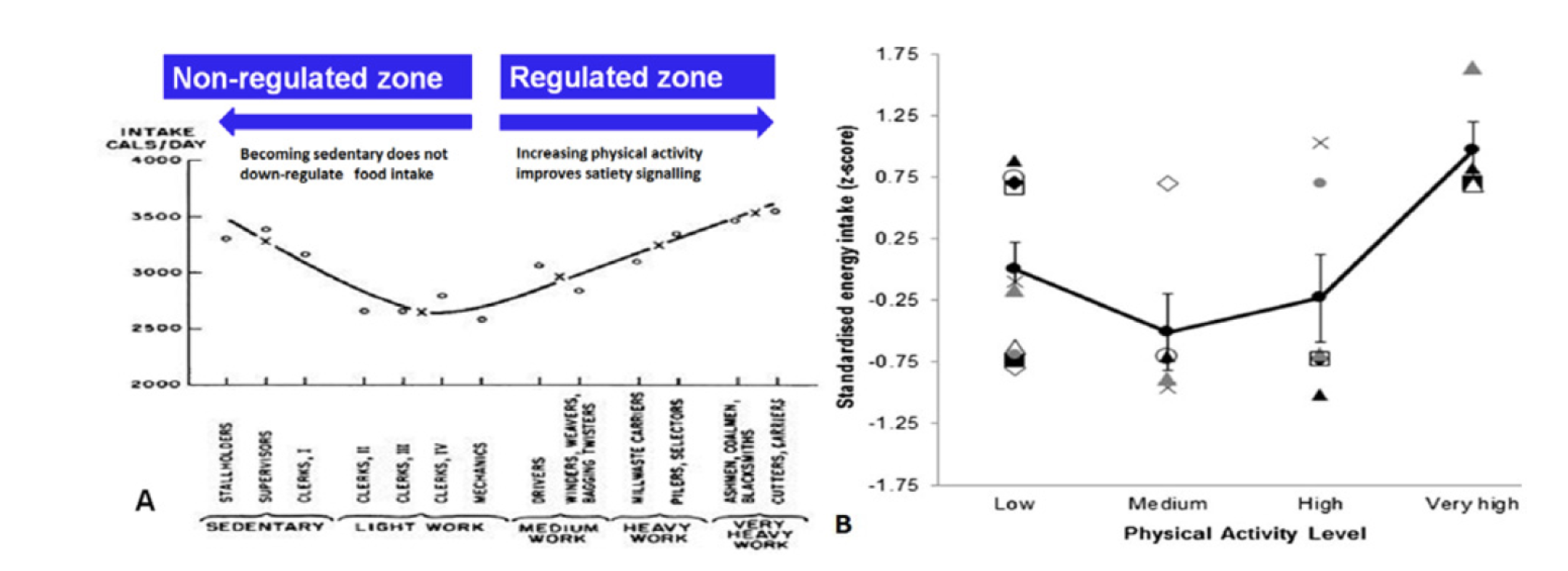

Indeed, we see that physical activity follows a U curve in relation to appetite (8,28).

If you go from sedentary to a higher activity level, you’ll suppress your appetite more, but if you go from an already high activity level to extreme levels like hard manual labor or ultra-marathon running, you get hungrier.

Anyone can test this for themselves. Ever sit around all day on lazy weekend? You actually end up eating a ton of food despite barely moving.

But you ever go on a ridiculously long hike because your extroverted outdoor friends are obsessed with nature? Yeah, your hunger will also skyrocket on those days.

So the sweet spot for physical activity for minimizing hunger is in between those 2 extremes. Step count research also lines up with this. There are no health benefits beyond 8000 steps per day. Movement is good, but more isn’t always better (27).

So make strength training as part of your life as much as you can thanks to it’s appetite suppressing effects and muscle growing benefits. Beyond that, get your steps in and/or do some cardio, but more exercise beyond that can be detrimental to your appetite, especially if your job is already physically active.

Now I’ll discuss some nutritional factors of satiety. Might as well start with protein as that seems to be the poster macro of the fitness industry. While protein is extremely important for satiety (44-47), it’s not the king of satiety many make it out to be.

Protein fills you up by increasing satiety hormones and decreasing hunger hormones (29), although these effects can be inconsistent (30-33).

Protein leverage theory is the key principle for understanding protein and hunger (34). Basically, protein is necessary to maximize satiety, but it loses it’s appetite-suppressing effects as you get closer to optimal amounts (48).

This is why protein is seemingly the most satiating macro. Your brain drives you to eat more protein if it doesn’t sense enough (35,36).

It also loses it’s satiating effects after habitually high protein intake and gains it back after habitually low protein intakes (37,38). Keep in mind, protein is not worth lowering below optimal intakes due to the acute effects of protein leverage theory, not to mention, protein still grows the same muscle even after habitual use (39).

In addition, the satiating effects of protein also decrease if you’re sleep deprived or as you get leaner (40,170). I see the body fat effect of protein in clients all the time. Take an overweight individual who’s barely eaten protein before and they’ll feel like their stomach is about to explode trying to include protein at each meal.

However, lean individuals have no problem eating protein. Fitness enthusiasts feel no difference adding 3 scoops vs 2 scoops of protein powder in their shake and they can chow down chicken and egg whites for days.

So the goal is to eat enough daily, but more each day isn’t always the best strategy if you’re still hungry.

Muscle mass benefits caps off at 1.6-1.8 grams per kg of bodyweight daily (41,42) and the satiety literature agrees with this as there are no study that shows more benefit when comparing this amount to a higher amount (43).

In fact, even below this amount, we have a wealth of studies, meta-analysis, and reviews showing the satiating effects of protein end before this, usually around 15% of energy intake even in bigger individuals (31,48-58,166).

Some research in the elderly shows whey shakes don’t even suppress appetite and can increase it. People end up eating less, but not enough to compensate for the shakes (164,165).

So while protein is mandatory to have for maximum satiety, once you get enough, it’s time to look towards other factors that don’t have a ceiling for their effects. Enter energy density.

Energy density is likely the food factor that impacts satiety the greatest. It’s simply a fancy word meaning how much volume and weight a food provides relative to it’s caloric content. When it comes to being full, your body cares more about feeling more volume as opposed to actually getting more calories (59).

So from a fat loss perspective, less energy density is better because it means for fewer calories, you get more pressure on your stretch receptors within your gut that signals for fullness.

This is why foods with a lot of water, air, and volume like porridge, popcorn, and potatoes are extremely filling (60).

This is also why zero calorie beverages are highly satiating, especially if they’re carbonated thanks to the bubbles adding volume in the gut (61,62,63).

On the contrary, caloric beverages like non-diet sodas and juice are bad for satiety as they satiate you to the same degree, but cost you lots of extra calories.

Fiber also makes foods less energy dense by providing less digestible energy. In addition, fiber has it’s own inherent satiating effect by slowing digestion, forcing you to chew, and enhancing gut health which signals to the brain for further fullness (64-68).

Every 14 grams of fiber reduces free eating caloric intake by 10% (69). That’s substantial and loading up on fiber will quickly annihilate your appetite.

Fiber is arguably the true king of satiety. Fibrous foods in a one to one comparison dominantly outperform less fibrous counterparts consistently in research.

For example, mushrooms matched for volume is more filling than beef even when beef has more calories and protein (70).

And if you match for calories (which you should), fiber outperforms protein and pretty much anything else by a longshot (71,72).

Think about it, if you finished a meal and you’re still hungry. You have 100 calories left to spend on anything.

If you spent it on kit kat, you’d get 1 and a half wafer.

If you spent it on chicken breast, you’d get about 88 grams of raw chicken which would be even less after cooking it.

If you spent it on carrots, you’d get 250 grams worth of carrots which is over half a pound.

Most people wouldn’t even be able to stomach down that much carrots which is why I often challenge my clients to eat an absurd amount of veggies. With most people, you’re not chronically hungry, you’re simply never eating enough vegetables.

Vegetables in particular are by far the most satiating food group with fruit as a close second. Eating these before your meals or within your meals will highly boost satiety (73,81).

A good rule of thumb is to have at least 1-2 fistfuls of veggies at almost every meal or 300-400 grams per day. More is always better because somewhere your mom is still telling you to eat your veggies.

As for fruit, you can eat them as your caloric needs allow for, but I generally suggest aiming to eat at least 1-2 servings each day.

When lifting weights, you’re trying to make your muscles thicker, harder, and more solid. You should be doing the same with food by optimizing viscosity, a fancy word meaning thick.

Viscosity adds texture and forces more chewing to stimulate further fullness (82). This is why solid, thicker foods are more filling than liquid ones (83-86).

Casein which is thicker than whey is more filling in the long term (87). Even blending your protein a bit longer to fluff it up with air makes it more filling (62).

Furthermore, replacing you protein shakes altogether for whole protein like chicken or fish further increases fullness (88).

So like many other things in life, thicker is better. Simply switching to a thicker yogurt brand or adding whole nuts instead of nut butter to your oatmeal are easy choices to further slay hunger.

Protein is necessary because your body leverages hunger to get sufficient protein. Fiber is also critically powerful to include in your diet. But, apart from fiber, we practically need to eat some sugar, starch, and fat, so which is more filling, carbs vs fat?

Well, if you match for energy density and control for fiber, fat and carbs are equally satiating because as discussed earlier, energy density is most important (89,90,93). For example, almonds/chocolate are as filling as rice cakes (91). And almonds are more filling than cereal bars (92).

Avocado is also more filling than oatmeal, but this confounded by fiber as avocados have over 2 and half times as much fiber (94).

Another confounding factor is the type of fat. Unsaturated fat is clearly more filling than saturated fat (95,96). For example, fish is significantly more filling than beef (97).

Furthermore, women are slightly more satiated from fat than men (98,99). And some obesity research shows metabolically unhealthy populations do better with low carb diets.

When looking at data that matches for calories instead of energy density, we see satiety favors carbs especially in a variety of populations thanks to carbs being less energy dense (100,101,102,169).

Although, periodically fat does outperform carbs, but only in insulin resistant subjects (104).

Beasley et al 2009 gives us the final piece of this puzzle (103). They found that an equal calorie diet of unsaturated fat was just as satiating in women as another higher in carbs.

So it makes sense that carbs are generally more satiating. Fat is more energetically dense at 9 calories per grams and fattier foods like fish, avocados, and eggs need other macros like protein or fiber to even compete on a satiety.

In a nutshell, fat can be more filling in some rare scenarios, but these effects likely won’t match the satiating effects of carbs unless you’re a bigger woman eating mostly unsaturated sources.

Thus, here are some practical takeaways to optimizing your carbs and fat for satiety.

Before I end this section, keep in mind the carb to fat ratio makes much less difference than many of the other factors like overall food choice and total fiber intake, so don’t get too hung up over all the carb vs fat debates on the internet.

One of the most important factors in hunger management is meal regularity. Because satiety partly depends on how you digest and the cascading effects post digestion, your circadian rhythm aka your internal clock needs to be well adjusted to this.

When you eat a random times, you’ll disrupt your appetite and the strength of food signals resulting in more hunger than necessary (105,106,122). This effect is magnified in women as they are significantly fuller with a regular eating schedule, but also significantly hungrier with an irregular eating schedule (107).

I see this all the time. The perpetually “busy” client who doesn’t plan for anything wonders why they’re hungry all the time and end up at a McDonald’s drive thru every other night. Set your meal times as non-negotiable meetings and have an idea of what you’ll eat each day. You can still be flexible and eat within an hour of that time or make changes if needed, but the more consistent, the better.

A preload is eating something before a meal to reduce how much you end up consuming. Protein and fibrous fruits/veggies consistently perform well as preloads.

Another way is to simply drink water before a meal to fill up your stomach (115,116). Do this for all meals and you can reduce caloric intake quite a bit.

Even rinsing your mouth with olive oil prior to a meal will trigger a fullness response as your mouth detects fat (117).

There are a few supplements I recommend if hunger is still an issue.

Apple cider vinegar is the first if you count that as a supplement. It’s been shown to reduce hunger in both lean and obese subjects making it an easy hunger fighting weapon in your arsenal (108,109).

At 3 calories per tablespoon, it’ll cost you almost nothing. 1-2 tablespoons before or after a meal is the general recommendation. Make sure to mix it with water or else it’ll burn your mouth like demon’s urine.

The next supplement are fiber supplements which is always less effective than fiber from whole foods (110,111).

However, fiber supplements still work especially if you’re undereating your fiber (112). Psyllium husk in particular can increase satiety and delay hunger (113,114).

The last supplement to consider is calcium as calcium has a direct impact on appetite regulation (118). Being deficient in calcium is fairly common especially in women due to their higher calcium needs and people who don’t eat dairy.

Indeed, appetite is further suppressed when calcium deficiencies are corrected (119,120,121). So be sure to eat dairy, sardines (w/ the bones), and spinach. If not, taking a calcium supplement will help.

Getting less sleep sucks for everything including your appetite. Short term sleep deprivation as little as one night of 4-7 hours instead of 8 can increase calorie intake by 20-22% (123,124).

You want to eat 20% less food tomorrow? Go to bed early tonight instead of staying up, stalking your ex on Instagram.

This section is short, but is arguably one of the most important. For a deep dive into how to get better sleep, check out this article.

Grab my Free Lifter’s Guide to Managing Stress

Ok time to learn about appetite psychology.

Growing up, my mom taught me to eat all I was served. If my sister or I wasted food, my mom would whoop us with a spatula into the next dimension. Even if you didn’t grow up in an intense Asian household, many of us embody the “clean plate effect” which means we naturally eat what we’re served (125,126).

If we have more food in front of us, we’ll eat it, hence why I can down an entire pint of Ben and Jerry’s in one sitting (127,128).

Bigger containers and plates also cause us to fill the space to fit what we think our servings should be even when serving others (129,130,131). This is why buffets have moderate and not big plates. With bigger plates, you’ll take more of their food.

One study gave movie goers different sized buckets of fresh or stale popcorn. Participants clearly ranked the stale popcorn as less yummy, but what’s interesting is everybody ate significantly more popcorn if they were served popcorn in a bigger bucket even with the mediocre stale popcorn (132).

Even in people who’ve been trained to reduce calories, when given bigger servings, they still naturally eat more without conscious restraint (133).

Fortunately, the portion size has little to do with fulfilling food reward (134). If you really think about it. Do you really need to eat a full rack of ribs because it’s extra rewarding? No, most of us do so because we’re simply served a full rack.

If you ordered a full rack and they gave you one or less ribs, you wouldn’t even notice.

Diet psychology bleeds into other examples as well. For instance, sandwiches are traditionally served with 2 slices of bread. If you get married to the idea of having to have 2 slices, you’ll be far less satiated than predicted if only presented with 1 slice (135). This is called associative learning where you associate satiety with certain arbitrary things.

For example, if you accept eggs are a breakfast food and chicken is a dinner food, you’re not only limited on food choices, but you’ll be less satiated if you’re forced to eat chicken for breakfast or eggs for dinner.

In fact, if you’re not mindful about how your psychology is playing tricks on you, someone can simply get you to eat 41% more food by telling you they halved your portion even when they didn’t (136).

One very interesting study gave the subjects a 3-egg omelet on 2 separate occasion. On one occasion, the subjects were told the omelet had 4 eggs and on the other occasion they were told it was a 2 egg omelet. Despite being the same 3-egg omelet, participants were more satiated after being told they ate 4 eggs and hungrier after being told they only ate 2 (137).

Fortunately, humans can consciously mitigate this to a certain extent.

The first step is learning how to track calories and truly knowing your portion sizes, so you’re not left to the propaganda of your brain.

Going hand in hand with that, using smaller plates, consciously limiting your portion sizes, and preparing meals ahead of time have all been shown to be effective strategies (138-141).

At restaurants, you can control your portions too. Immediately ask the waiter for however much you plan on eating to be served and to package the rest in a to go box immediately. This is not one of those cheesy advice you commonly hear from coaches. It’s backed by research to directly cause people to eat less (142). If you’re unsure of how much to ask, simply request half the usual portion.

Furthermore, smaller forks and spoons are better because they make your portions appear bigger and force you to take more bites (143).

Lastly, think twice about buying fancy colored plates or using your favorite childhood Tom & Jerry plate. Simple white plates cause people to eat the least compared to black or red due to contrasting stronger with food and thus making your serving size appear bigger (144).

The psychology about how you approach a meal, think about food, and your platform for serving food all impact your hunger.

How fast you eat and when you stop matters as well.

As described earlier, the satiety cascade starts in your mouth (145). That’s where you can first optimize for satiety. The idea, that eating slower helps your body register fullness later is misleading.

You should still eat slow, but emphasize chew volume. Chewing fulfills the food reward pathways and triggers satiety independent of how tasty the food is (146,147). This is why chewing gum is a great appetite suppressant and likely a good idea to keep chewing even after it loses it’s flavor (148,149,150).

Eating slower also encourages more water consumption between bites which also decreases energy intake (151,152,153).

Eating slower as a whole seems to be a good recommendation to lower food intake, especially for overly tasty foods like donuts, pizzas, and fries (154,155,156,162).

Keep in mind, slower eating doesn’t mean smaller bites though. Telling somebody to take smaller bites simply makes them eat slower, not necessarily eat less (157). This makes sense as smaller bites are less rewarding. Imagine somebody telling you to eat a chicken nugget in 10 bites. While you get to enjoy the chicken nugget longer, each bite isn’t pleasurable enough to satisfy you and signal for the same dose of fullness.

Now that we’ve covered eating rate, let’s talk eating end point.

Always ask yourself, am I still enjoying this food and do I really need this next bite? The key during weight loss is to eat till you’re comfortably full not maximally full. At some point, your appetite can easily keep going, but hunger has already been fulfilled (158).

Slow and mindful eating is more relevant for men.

Research finds that if men had it their way, they would eat until they’re maximally full while women will stop short (159).

Men also generally eat faster and increase their intake of both nutritious and junk food in the presence of women (160,161). Cause you know, girls totally get turned on from seeing you clean out a buffet.

That was sarcastic of course, but research does find slow eating lowers energy intake far greater in men (163). Regardless though, everyone should learn to take their time, chew their food, and actually savor the flavor better.

Oh snap, we’re at the conclusion! Now you can call yourself a mighty emperor who’s fully equipped to vanquish any hunger in sight.

This is the part where I sometimes do a recap with the key takeaways in cute bullet points, but there are too many and I sort of have a life outside of writing too. So, go back and take notes if you have to.

And be sure to stay tuned for part 2 of this article where I’ll talk in detail about how to tackle specific food cravings.

Dirlewanger M;di Vetta V;Guenat E;Battilana P;Seematter G;Schneiter P;Jéquier E;Tappy L; “Effects of Short-Term Carbohydrate or Fat Overfeeding on Energy Expenditure and Plasma Leptin Concentrations in Healthy Female Subjects.” International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders : Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11126336/.

Yang, Chia-Lun, and Robin M. Tucker. “Beneficial Effects of a High Protein Breakfast on Fullness Disappear after a Night of Short Sleep in Nonobese, Premenopausal Women.” Physiology & Behavior, Elsevier, 29 Nov. 2020, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031938420305837?via%3Dihub.

Grab my free checklist on how to defeat your worst food cravings

In this article, I only talk about how to master intuitive eating. I went over the pros and cons of it in a previous article, so read that one first.

Being lactose intolerant sucks. If you even think about drinking some milk, your life suddenly becomes an unpleasant series of violent farts, bloating, and explosive diarrhea.

Cholesterol was once thought of as a dangerous artery clogging nutrient. Fortunately, research shows cholesterol is not the enemy we once thought it was.