1. Batra. “Relationship of Cravings with Weight Loss and Hunger. Results from a 6 Month Worksite Weight Loss Intervention.” Appetite, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23684901/.

2. White . “Development and Validation of the Food-Craving Inventory.” Obesity Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11836456/.

3. Cynthia M Kroeger, John F Trepanowski. “Eating Behavior Traits of Successful Weight Losers during 12 Months of Alternate-Day Fasting: An Exploratory Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial – Cynthia M Kroeger, John F Trepanowski, Monica C Klempel, Adrienne Barnosky, Surabhi Bhutani, Kelsey Gabel, Krista A Varady, 2018.” SAGE Journals, journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0260106017753487.

4. Monrroy, Hugo, et al. “Meal Enjoyment and Tolerance in Women and Men.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 8 Jan. 2019, www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/1/119.

5. Ulusoy . “Are People Who Have a Better Smell Sense, More Affected from Satiation?” Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27658749/.

6. Raghunathan, Rajagopal, et al. The Unhealthy = Tasty Intuition and Its Effects on Taste Inferences, Enjoyment, and Choice of Food Products. www.jstor.org/stable/30162121.

7. Heijden, Amy van der, et al. “Healthy Is (Not) Tasty? Implicit and Explicit Associations between Food Healthiness and Tastiness in Primary School-Aged Children and Parents with a Lower Socioeconomic Position.” Food Quality and Preference, Elsevier, 27 Mar. 2020, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0950329320302081.

8. P;, Crum. “Mind over Milkshakes: Mindsets, Not Just Nutrients, Determine Ghrelin Response.” Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21574706/.

9. Gilhooly, C H, et al. “Food Cravings and Energy Regulation: the Characteristics of Craved Foods and Their Relationship with Eating Behaviors and Weight Change during 6 Months of Dietary Energy Restriction.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 26 June 2007, www.nature.com/articles/0803672.

10. “Evening Ready-to-Eat Cereal Consumption Contributes to Weight Management.” Taylor & Francis, www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07315724.2004.10719374.

11. WL;, Stanhewicz. “Determinants of Water and Sodium Intake and Output.” Nutrition Reviews, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26290293/.

12. PMC, Europe. Europe PMC, europepmc.org/article/med/9891606.

13. DM;, Baumeister. “Ego Depletion: Is the Active Self a Limited Resource?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9599441/.

14. Bernecker, Katharina, and Veronika Job. “Beliefs about Willpower Moderate the Effect of Previous Day Demands on next Day’s Expectations and Effective Goal Striving.” Frontiers in Psychology, Frontiers Media S.A., 14 Oct. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4604262/.

15. C;, Havermans. “Eating and Inflicting Pain out of Boredom.” Appetite, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25447018/.

16. Roe, Liane S., and Barbara J. Rolls. “Which Strategies to Manage Problem Foods Were Related to Weight Loss in a Randomized Clinical Trial?” Appetite, Academic Press, 29 Mar. 2020, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195666319314011?fbclid=IwAR3ZBWEs4cpbagq9KQoDe7iKKQNPCD0y8z6-YAgxhE724HJF9i5zJ8Hbxrg.

17. de Macedo . “The Influence of Palatable Diets in Reward System Activation: A Mini Review.” Advances in Pharmacological Sciences, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27087806/.

18. Validate User, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/101/5/908/4564476.

19. Schulte, Erica M., et al. “Which Foods May Be Addictive? The Roles of Processing, Fat Content, and Glycemic Load.” PLOS ONE, Public Library of Science, journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0117959.

20. Nadeau, Julie, et al. “Teaching Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes How to Incorporate Sugar Choices Into Their Daily Meal Plan Promotes Dietary Compliance and Does Not Deteriorate Metabolic Profile.” Diabetes Care, American Diabetes Association, 1 Feb. 2001, care.diabetesjournals.org/content/24/2/222.short.

21. Marlatt . “Persistence of Weight Loss and Acquired Behaviors 2 y after Stopping a 2-y Calorie Restriction Intervention.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28275127/.

22. JL;, Temple. “Behavioral Sensitization of the Reinforcing Value of Food: What Food and Drugs Have in Common.” Preventive Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27346758/.

23. Zellner. “Food Liking and Craving: A Cross-Cultural Approach.” Appetite, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10447980/.

24. “Handbook of Diet and Nutrition in the Menstrual Cycle, Periconception and Fertility.” Human Health Handbooks, www.wageningenacademic.com/doi/10.3920/978-90-8686-767-7_9.

25. E;, Zellner. “Chocolate Craving and the Menstrual Cycle.” Appetite, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15036792/.

26. Hormes, Julia M, and Martha A Niemiec. “Does Culture Create Craving? Evidence from the Case of Menstrual Chocolate Craving.” PloS One, Public Library of Science, 19 July 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5517000/.

27. Michener, Willa, and Paul Rozin. “Pharmacological versus Sensory Factors in the Satiation of Chocolate Craving.” Physiology & Behavior, Elsevier, 13 Feb. 2003, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0031938494902836.

28. A;, Meule. “A Short Version of the Food Cravings Questionnaire-Trait: the FCQ-T-Reduced.” Frontiers in Psychology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24624116/.

29. Davelaar. “The Demise of Short-Term Memory Revisited: Empirical and Computational Investigations of Recency Effects.” Psychological Review, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15631586/.

30. Apolzan . “Frequency of Consuming Foods Predicts Changes in Cravings for Those Foods During Weight Loss: The POUNDS Lost Study.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28618170/.

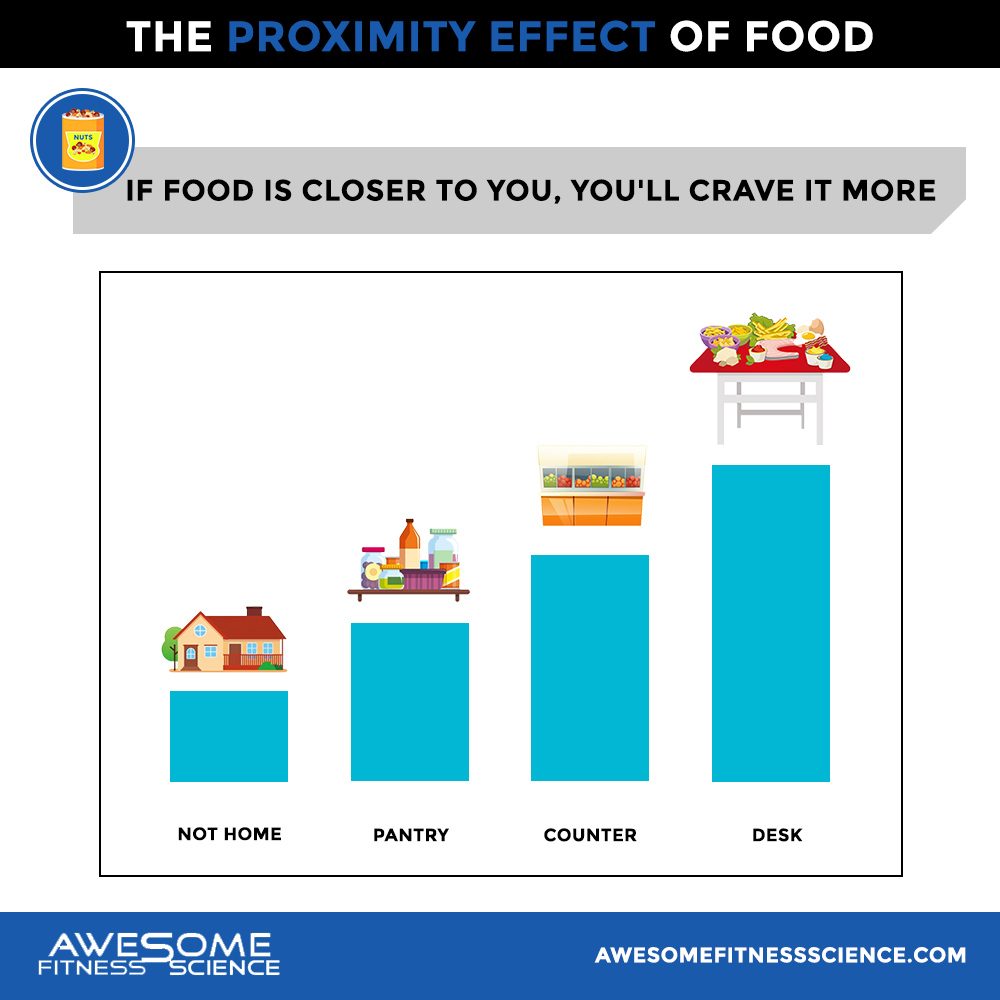

31. Hunter, Jennifer A, et al. “Effect of Snack-Food Proximity on Intake in General Population Samples with Higher and Lower Cognitive Resource.” Appetite, Academic Press, 1 Feb. 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5768324/.

32. CL. Ogden, MD. Carroll, et al. “Proximity of Food Retailers to Schools and Rates of Overweight Ninth Grade Students: an Ecological Study in California.” BMC Public Health, BioMed Central, 1 Jan. 1970, bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-11-68.

33. DiFeliceantonio, Alexandra. “Supra-Additive Effects of Combining Fat and Carbohydrate on Food Reward.” Cell, www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(18)30325-5.

34. Altering the Availability or Proximity of Food, Alcohol, and Tobacco Products to Change Their Selection and Consumption, www.cochrane.org/CD012573/PUBHLTH_altering-availability-or-proximity-food-alcohol-and-tobacco-products-change-their-selection-and.

35. Validate User, academic.oup.com/jn/article/150/5/1324/5736353.

36. R;, Alberts. “Coping with Food Cravings. Investigating the Potential of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention.” Appetite, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20493913/.

37. Forman . “A Comparison of Acceptance- and Control-Based Strategies for Coping with Food Cravings: an Analog Study.” Behaviour Research and Therapy, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17544361/.

38. Schumacher, Sophie, et al. “The Food Craving Experience: Thoughts, Images and Resistance as Predictors of Craving Intensity and Consumption.” Appetite, Academic Press, 22 Nov. 2018, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195666318310304.

39. Forman . “Comparison of Acceptance-Based and Standard Cognitive-Based Coping Strategies for Craving Sweets in Overweight and Obese Women.” Eating Behaviors, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23265404/.

40. Daniel, Tinuke Oluyomi, et al. “The Future Is Now: Reducing Impulsivity and Energy Intake Using Episodic Future Thinking.” Psychological Science, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Nov. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4049444/.

41. Hollis-Hansen, Kelseanna. “Episodic Future Thinking and Grocery Shopping Online.” Appetite, Academic Press, 18 Oct. 2018, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195666318310225.

42. Moynihan, Andrew B. “Eaten up by Boredom: Consuming Food to Escape Awareness of the Bored Self.” Frontiers in Psychology, Frontiers Media S.A., 1 Apr. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4381486/.

43. SD;, Wang. “Influence of Sleep Restriction on Weight Loss Outcomes Associated with Caloric Restriction.” Sleep, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29438540/.

44. Shechter . “Alterations in Sleep Architecture in Response to Experimental Sleep Curtailment Are Associated with Signs of Positive Energy Balance.” American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22972835/.

45. Zhu, Bingqian. “Effects of Sleep Restriction on Metabolism-Related Parameters in Healthy Adults: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, W.B. Saunders, 10 Feb. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1087079218301941.

46. Bosy-Westphal . “Influence of Partial Sleep Deprivation on Energy Balance and Insulin Sensitivity in Healthy Women.” Obesity Facts, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20054188/.

47. Alhola, Paula. “Sleep Deprivation: Impact on Cognitive Performance.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Dove Medical Press, 2007, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2656292/.

48. J;, Orzeł-Gryglewska. “Consequences of Sleep Deprivation.” International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20442067/.

49. Al Khatib, Haya K. “Sleep Extension Is a Feasible Lifestyle Intervention in Free-Living Adults Who Are Habitually Short Sleepers: a Potential Strategy for Decreasing Intake of Free Sugars? A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 10 Jan. 2018, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/107/1/43/4794751.

50. Leproult. “Sleep Loss Results in an Elevation of Cortisol Levels the next Evening.” Sleep, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9415946/.

51. CA;, Torres. “Relationship between Stress, Eating Behavior, and Obesity.” Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17869482/.

52. Broussard, Josiane L. “Elevated Ghrelin Predicts Food Intake during Experimental Sleep Restriction.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 15 Oct. 2015, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/oby.21321.

53. Beydoun, May A. “Pathways Linking Socioeconomic Status to Obesity through Depression and Lifestyle Factors among Young US Adults.” Journal of Affective Disorders, Elsevier, 22 Oct. 2009, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S016503270900439X.

54. Gebreab, Samson Y. “The Contribution of Stress to the Social Patterning of Clinical and Subclinical CVD Risk Factors in African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study.” Social Science & Medicine, Pergamon, 13 July 2012, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953612004807.

55. Clauss, Nikki. “Exposure to a Sex-Specific Stressor Mitigates Sex Differences in Stress-Induced Eating.” Physiology & Behavior, Elsevier, 23 Jan. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031938418309090.

56. Legget, Kristina T. “Harnessing the Power of Disgust: a Randomized Trial to Reduce High-Calorie Food Appeal through Implicit Priming.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 24 June 2015, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/102/2/249/4564568.

57. Mehl, Nora. “Unhealthy Yet Avoidable-How Cognitive Bias Modification Alters Behavioral and Brain Responses to Food Cues in Individuals with Obesity.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 18 Apr. 2019, www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/4/874.

58. R;, Chao. “Food Cravings, Food Intake, and Weight Status in a Community-Based Sample.” Eating Behaviors, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25064302/.

59. Lampuré, Aurélie. “Sociodemographic, Psychological, and Lifestyle Characteristics Are Associated with a Liking for Salty and Sweet Tastes in French Adults.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 28 Jan. 2015, academic.oup.com/jn/article/145/3/587/4743713.

60. Holt, S.H.A. “Dietary Habits and the Perception and Liking of Sweetness among Australian and Malaysian Students: A Cross-Cultural Study.” Food Quality and Preference, Elsevier, 10 Apr. 2000, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0950329399000762.

61. H.A. Jamel, A. Sheiham. “Taste Preference for Sweetness in Urban and Rural Populations in Iraq – H.A. Jamel, A. Sheiham, C.R. Cowell, R.G. Watt, 1996.” SAGE Journals, journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/00220345960750111001.

62. Nock. “Reduction in Neural Activation to High-Calorie Food Cues in Obese Endometrial Cancer Survivors after a Behavioral Lifestyle Intervention: a Pilot Study.” BMC Neuroscience, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22731395/.

63. Buckland. “A Low Energy-Dense Diet in the Context of a Weight-Management Program Affects Appetite Control in Overweight and Obese Women.” The Journal of Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30053284/.

64. Anguah . “Can the Palatability of Healthy, Satiety-Promoting Foods Increase with Repeated Exposure during Weight Loss?” Foods (Basel, Switzerland), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28231094/.

65. Martin, Corby K. “Change in Food Cravings, Food Preferences, and Appetite During a Low‐Carbohydrate and Low‐Fat Diet.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 6 Sept. 2012, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1038/oby.2011.62.

66. Murdaugh, Donna L. “FMRI Reactivity to High-Calorie Food Pictures Predicts Short- and Long-Term Outcome in a Weight-Loss Program.” NeuroImage, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Feb. 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3287079/.

67. Anton . “Diet Type and Changes in Food Cravings Following Weight Loss: Findings from the POUNDS LOST Trial.” Eating and Weight Disorders : EWD, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23010779/.

68. Alcock, Joe. “Is Eating Behavior Manipulated by the Gastrointestinal Microbiota? Evolutionary Pressures and Potential Mechanisms.” BioEssays : News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, WILEY Periodicals, Inc., Oct. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4270213/.

69. Temko, Jamie E. “The Microbiota, the Gut and the Brain in Eating and Alcohol Use Disorders: A ‘Ménage à Trois’?” Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), Oxford University Press, 1 July 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5860274/.

70. Gibson, E.l. “Chocolate Craving and Hunger State: Implications for the Acquisition and Expression of Appetite and Food Choice.” Appetite, Academic Press, 25 May 2002, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195666398902070.

71. Tajiri . “Acute Sleep Curtailment Increases Sweet Taste Preference, Appetite and Food Intake in Healthy Young Adults: A Randomized Crossover Trial.” Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32024073/.

72. Proserpio, Cristina, et al. “Ambient Odor Exposure Affects Food Intake and Sensory Specific Appetite in Obese Women.” Frontiers in Psychology, Frontiers Media S.A., 15 Jan. 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6340985/.

73. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/oby.22082