Stop Gossiping About the Innocent Leg Extension

Every gym I’ve worked at, there was always that one overly functional trainer or group of trainers who demonized the leg extension

Think of your most stubborn muscle group that’s so painfully small despite how hard you train it. Perhaps, it’s your narrow back, your chopstick calves, or that flat butt your girlfriend teases you about.

One reason it could be so small is your exercise order. Yes, the sequence in which you perform your exercises matters. This should be obvious because the sequence of everything in life matters.

Getting a job before becoming a dad is normal, but becoming a dad before getting a job makes you look like a loser.

Putting cereal before the milk is appropriate. Putting the milk before the cereal makes you a psychopath. Don’t debate me on this one you milk first people. Y’all need a brain scan.

Anyways, you get the idea. Here’s everything you need to know about sequencing which exercises come first, second, third, etc.

First, you need to understand fatigue. Fatigue is one of those things people think of after the workout like when they’re feeling sore, but fatigue is accumulating during your workout as well, even after the first set. And by definition, fatigue will impair your subsequent performance (1).

With every set, your muscles fill with blood and experience micro tears while your brain/nervous system deplete in battery life like Iron man’s suit as he fights off waves of villains.

Thus, after every set, your body produces less force, lose joint support, and impairs your brain’s skill coordination (2-6).

Where am I going with all this fatigue talk? Well because fatigue drops your muscle activation and skill on subsequent sets, the exercises you place earlier in the workout receives the best performance, stimulation, and unsurprisingly, the best adaptations (7,21).

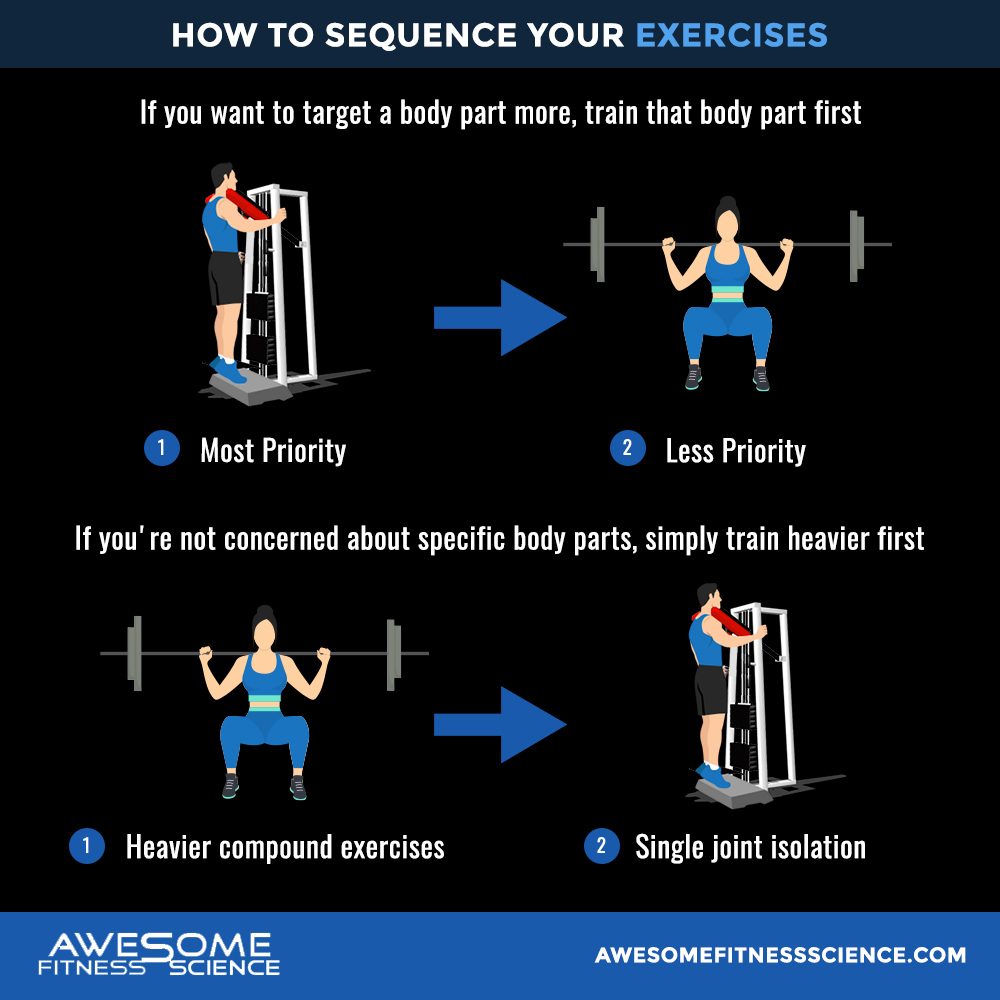

This means you should place what you need the most growth from first in the workout to maximize that exercise’s performance.

For example, many guys would never put machine rows before barbell benching, but that’s what you need to do if your back is weak and tiny.

Same goes for the guys who complain about their calves. Most of them start their leg day with squats, deadlifts, and leg presses before finishing with calves. They train calves as more of an afterthought without realizing plenty of fatigue has accumulated especially in the nervous system. This prevents all muscle fibers from being recruited later (8,9,10).

So if you’re training calves at the end of a strenuous workout, not all muscle fibers are being stimulated and growth is compromised. Somebody desiring bigger calves should train them first not last.

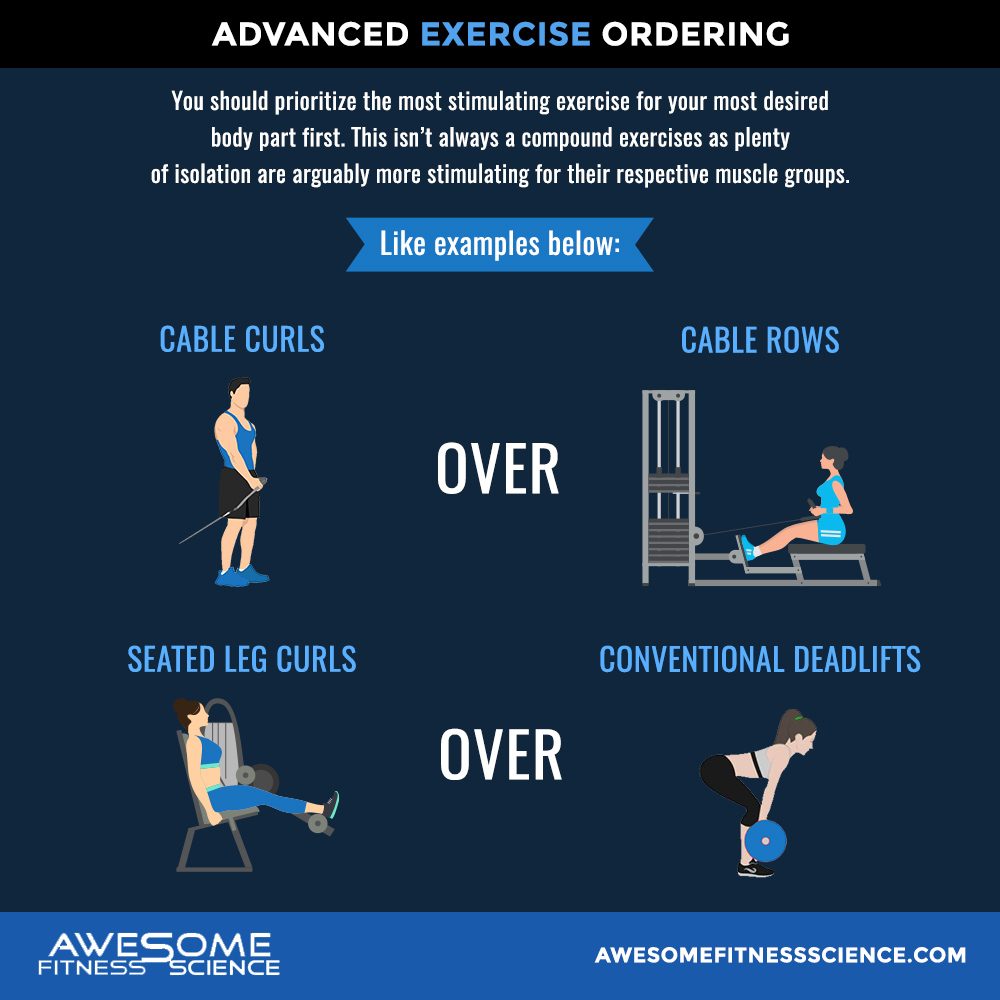

That’s the first rule in understanding exercise order. You should prioritize the most stimulating exercise for your most desired body part first. This isn’t always a compound exercises as plenty of isolation are arguably more stimulating for their respective muscle groups like cable curls are superior for biceps over cable rows and seated leg curls are superior for hamstrings over conventional deadlifts.

However, if you’re not concerned about prioritizing certain body parts or specific lifts for strength, heavy compound first should be the default rule of thumb (19).

Heavier compound exercises require the most skill, coordination, and demand the most from your nervous system and joints. It’s best to do these when you’re fresh.

The later you do a compound exercise, the more it suffers in performance. If you did an isolation prior to a compound, you would get the same muscle growth for that muscle, but because the compound compromised it’s total reps, the other muscles that the compound exercise would have trained don’t get as stimulated (7,11,12,13).

For example, if you did bench press before triceps extensions, you’d get more thorough stimulation.

If you did triceps extensions first, your bench press performance would suffer in favor of more triceps extension performance. The net growth for your triceps would be the same, but because the exercise (bench press) that hits multiple muscles took the sacrifice, you compromised muscle growth for your chest/shoulders.

By doing compound first, you perform more total work or volume load for the same sets which can mean more long-term strength and muscle growth (14-17).

Furthermore, by doing more work, you’re technically burning more calories as well which can aid in minor fat loss, so dieters should do heavier compound exercises first (18).

By doing heavier lower rep lifts first, you also receive less neuromuscular fatigue early in your workout because higher reps are more fatiguing on a set/exercise equated basis. So if you got low rep back squats and high rep leg presses in a workout, the back squats should usually go first.

Lastly, by doing your heavier work first, you take advantage of the phenomenon known as post-activation potentiation (20). This is where your muscle cross-bridges rapidly improve their formation so it increases the potential of more weight/reps performed when you move onto lighter work.

This is why light stuff feels even lighter after holding heavier stuff.

Picture trying to throw a fat pig. After slinging the overweight walking pork chop, if you tried throwing a skinnier version afterwards, it would swing right out of your arms because the contrast makes the lighter pig feel much lighter than it would’ve. That’s basically post-activation potentiation in a nutshell.

But all this to say, you’ll maximize total work performance by doing the heavy lifts first.

Ok, so when it comes to sequencing your exercises, here’s what it comes down to.

1. S;, Behrens. “Effect of Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage

on Neuromuscular Function of the Quadriceps Muscle.” International Journal

of Sports Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22510801/.

2. Granata, Kevin P, et al. “Influence of Fatigue in

Neuromuscular Control of Spinal Stability.” Human Factors, U.S. National

Library of Medicine, 2004, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1633714/.

3. Hooper . “Effects of Fatigue from Resistance Training

on Barbell Back Squat Biomechanics.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning

Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24662156/.

4. WE;, Myers. “Proprioception and Neuromuscular Control

of the Shoulder after Muscle Fatigue.” Journal of Athletic Training,

U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16558590/.

5. PJ;, Hiemstra. “Effect of Fatigue on Knee

Proprioception: Implications for Dynamic Stabilization.” The Journal of

Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11665747/.

6. R;, Byrne. “Neuromuscular Function after

Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: Theoretical and Applied Implications.” Sports

Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14715039/.

7. “What Influence Does Resistance Exercise Order Have on

Muscular Strength Gains and Muscle Hypertrophy? A Systematic Review and

Meta-Analysis.” Taylor & Francis,

www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17461391.2020.1733672.

8. Taylor, Janet L, et al. “Neural Contributions to Muscle

Fatigue: From the Brain to the Muscle and Back Again.” Medicine and Science

in Sports and Exercise, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Nov. 2016,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5033663/.

9. AG;, Nordlund. “Central and Peripheral Contributions to

Fatigue in Relation to Level of Activation during Repeated Maximal Voluntary

Isometric Plantar Flexions.” Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. :

1985), U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12972439/.

10. Husmann.

“Impact of Blood Flow Restriction Exercise on Muscle Fatigue Development and

Recovery.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, U.S. National

Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29112627/.

11. Simão.

“Influence of Upper-Body Exercise Order on Hormonal Responses in Trained Men.” Applied

Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition Et

Metabolisme, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23438229/.

12. Avelar,

Ademar, et al. “Effects of Order of Resistance Training Exercises on Muscle

Hypertrophy in Young Adult Men.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and

Metabolism, 24 Sept. 2018,

cdnsciencepub.com/doi/abs/10.1139/apnm-2018-0478#.W6ouA-h_KUk.

13. 1Metabolism.

“Influence of Resistance Training Exercise Order on Muscle… : The Journal of

Strength & Conditioning Research.” LWW,

14. Department

of Exercise & Sport Sciences. “Manipulating Exercise Order Affects Muscular

Performance… : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research.” LWW,

15. Monteiro,

Walace, et al. “Manipulação Na Ordem Dos Exercícios e Sua Influência Sobre

Número De Repetições e Percepção Subjetiva De Esforço Em Mulheres Treinadas.” Revista

Brasileira De Medicina Do Esporte, Sociedade Brasileira De Medicina Do

Exercício e Do Esporte,

www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1517-86922005000200010.

16. Bentes

. “Acute Effects of Dropsets among Different Resistance Training Methods in

Upper Body Performance.” Journal of Human Kinetics, U.S. National

Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23487480/.

17. Wallace,

William, et al. “Repeated Bouts of Advanced Strength Training Techniques:

Effects on Volume Load, Metabolic Responses, and Muscle Activation in Trained

Individuals.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 6

Jan. 2019, www.mdpi.com/2075-4663/7/1/14.

18. Pina,

Fábio Luiz Cheche, et al. “Influence of Resistance Exercises Order on Body

Composition in Older Men.” Revista Da Educação Física / UEM,

Universidade Estadual De Maringá, www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1983-30832013000300011&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt.

19. Nunes,

João Pedro, et al. “Starting the Resistance-Training Session with Lower-Body

Exercises Provides Lower Session Perceived Exertion without Altering the

Training Volume in Older Women.” International Journal of Exercise Science,

Berkeley Electronic Press, 1 Nov. 2019,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6886617/.

20. Alves

. “Postactivation Potentiation Improves Performance in a Resistance Training

Session in Trained Men.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research,

U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31567790/.

21. Cardozo,

Diogo Correia, et al. “The Effect of Exercise Order in Circuit Training on

Muscular Strength and Functional Fitness in Older Women.” International

Journal of Exercise Science, Berkeley Electronic Press, 1 May 2019,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6533091/.

Sign up for AwesomeFitnessScience Weekly. You’ll get juicy insider secrets, updates, and stories.

Every gym I’ve worked at, there was always that one overly functional trainer or group of trainers who demonized the leg extension

Understanding tempo is like understanding females, guys think they know what they’re doing, but they don’t. For those that don’t know, tempo is how fast you lift and lower your reps.

All you want in life is to see the scale go down and the fat hanging off your waist vanish into thin air.