Ladies, Serious Strength Training will get you Toned Not Bulky

Hey ladies, you have so much going for you, but if I’m being honest, many of you avoid lifting weights to your detriment.

If you’ve ever attempted weight loss, you might’ve noticed as you lose more weight, the journey gets tougher.

You put in the exact same sacrifice day in and day out, but the results come slower and slower. Before you know it, the scale stops moving and you’re still stuck dieting with no further results to show for.

This plateau has led you to believe your metabolism has slowed down, got damaged somehow, or have caused you to enter the dreaded starvation mode where your body supposedly refuses to let go of your body fat like a clingy girlfriend.

Can your metabolism really be permanently damaged? And is starvation mode legit?

By the end of this, you’ll have full understanding of anything relating to your metabolism slowing down during weight loss and if things like metabolic damage and starvation mode have any truth to them.

To understand everything, it’s important you have a decent grasp on how weight loss works in the first place.

Weight loss works when you burn more total calories than you consume over time. Your body burns calories in 4 ways, your resting metabolism, food digestion, exercise, and non-exercise activity.

All 4 of these components make up your total energy expenditure which is the total calories you burn. If your total energy expenditure can exceed the energy (calories) you put in your mouth over time, weight loss will occur. This is called being in a caloric deficit.

If you still want more clarity on these basics, no worries. Go read my past article on this topic first if you’re not completely familiar with a caloric deficit.

As you lose weight, whether you lose 5 pounds or 50 pounds, all 4 aspects of your energy expenditure will go down (27). This slowdown in total calories burned is completely normal and a mandatory part of weight loss because your body is now transitioning to a newer lighter you.

Here’s the nitty gritty behind why each aspect of energy expenditure will decrease.

Your resting metabolism slows down to match someone smaller. It now doesn’t require as much energy to maintain it’s tissue because there’s less of it. Fat for example is a metabolically active tissue meaning your metabolism burns calories to maintain it (1). The more fat you lose, the less calories your new lighter body has to use up thus contributing to less total energy expenditure.

The same goes with muscle (2). In fact, muscle is even more metabolically demanding than fat, meaning losing muscle will slow down your metabolism to a greater degree, although muscle loss shouldn’t happen with intelligent dieting or with the exception of physique competitors.

The thermic effect of digestion also slows down because to lose weight, you have to eat less food and thus with less food to digest, your body won’t burn as many via digestion (3). This one is pretty straightforward and the effects are extremely minor as the calories burned from digestion are generally small to begin with.

Next is exercise. Lighter people burn less calories given the same movements. Let’s say you were 1000 lbs. I know you’re not, but let’s just pretend you are. If you did a jumping jack at a 1000 lbs, your body would have to burn a lot of calories to power that jump because it needs to move 1000 lbs. of mass in the air. However, after you’ve lost some weight, the calories burned from a jumping jack will be lowered.

Let’s say you got your life together and lost 200 lbs. Your new 800 lb body wouldn’t require as many calories to perform the same jumping jack. Studies show this is because your body’s work efficiency increases meaning it gets better at doing the same work while spending less energy especially because it now has lighter limbs to move (4).

And finally, there’s non-exercise activity thermogenesis otherwise known as NEAT. NEAT is the calories burned through physical activity apart from formal exercise (5). Walking and flossing are activities that would be considered as NEAT, but NEAT also includes spontaneous activities like blinking and fidgeting.

We’ve already established that smaller people will burn less calories for the same movements. This phenomenon also applies to all the NEAT related movements you do as well, so zipping up your jacket each morning or typing your daily good morning text to your girlfriend will expend less calories once you’re lighter.

In addition to this, as you become lighter, NEAT also reduces via spontaneous movement. You unknowingly blink slower and fidget less.

This entire process of energy expenditure decreasing is normal. You can’t expect your body to burn the energy of a truck when you’re now the size of a prius.

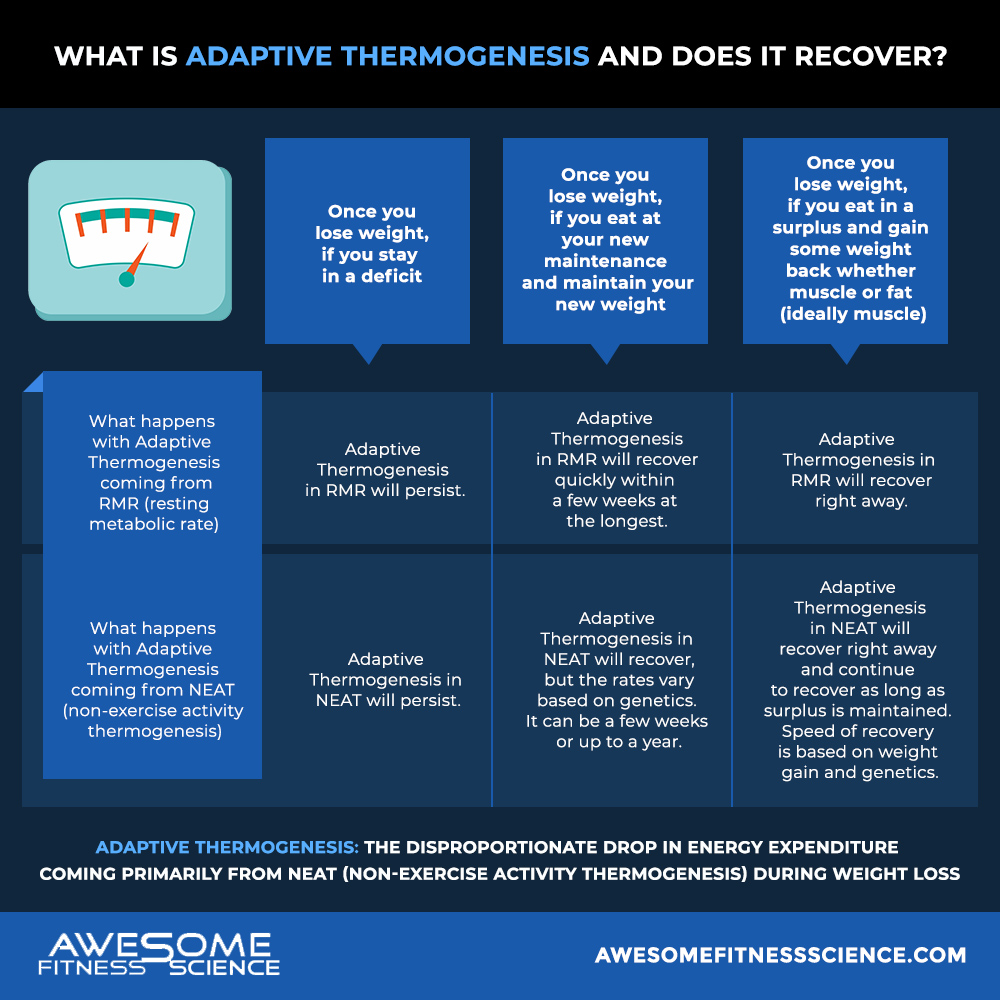

However, sometimes, our energy expenditure slows down beyond what’s predicted. This is called adaptive thermogenesis or metabolic adaptation (6,7).

Adaptive thermogenesis can be the culprit behind why plateaus happen even if you continue to eat a diet that was originally working great.

For example, let’s say hypothetically, your body and lifestyle burns at total of 2100 calories a day to maintain it’s current body weight. You then choose to eat a diet restricted to 1800 calories a day so you can get into a caloric deficit and lose weight.

However, as you lose weight, adaptive thermogenesis kicks in and total energy expenditure goes down beyond what’s predicted. Eventually, your body only burns 1800 calories given the same lifestyle.

Even though you’re still eating your restricted diet of 1800 calories, your now slightly lighter body is only burning 1800 calories with the same lifestyle. This means you’re no longer in a deficit and have plateaued.

Now that you understand adaptive thermogenesis is a normal part of any weight loss journey, you’re probably wondering if adaptive thermogenesis will damage your metabolism like some people say? Is adaptive thermogenesis the same as metabolic damage?

Indeed energy expenditure is lower in people who have lost weight when compared to someone already at that weight and muscle/fat ratio.

High quality research confirms this (7,8) while other research disagrees (9). This indicates adaptive thermogenesis doesn’t happen in everybody.

Fortunately, as I hinted at, adaptive thermogenesis doesn’t occur in your metabolism (7,8).

Studies show there’s no consistent evidence of disproportionate decreases in metabolism following weight loss even in people who stay at their new lighter weight for years (10,24).

So adaptive thermogenesis doesn’t really affect your metabolism and the term damage is a complete exaggeration.

One comprehensive review shows your metabolism doesn’t get any sort of damage in all cases of weight loss from rapid weight loss, competitive weight cutting, and even extreme cases of malnourished and anorexic patients (11). It also showed any potential disproportionate drop in metabolism is quickly reversed and in some cases gets even higher once a person stops dieting and increases calories back up.

A newer study found your metabolism nearly recovers after 4 weeks at maintenance and was fine after maintaining that weight for less than a year (28).

Your metabolism is extremely flexible and doesn’t get damaged. This is true even if you lose a lot of weight and regardless of how fast you lose it as long as you don’t lose muscle (10,12).

Research has even shown your metabolism can’t be damaged even if you’re a chronic yo-yo dieter who loses and gains the same weight back frequently (22,30). Any weight gain even unintentional reverses any drop in energy expenditure assuming you’re not losing muscle and gaining back fat.

The disproportionate drop in energy expenditure is from physical activity with about 85-90% or more of it coming from your non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) (7,23).

This is both good news and bad news.

The bad news is that NEAT is uncontrollable to an extent. Adaptive thermogenesis will decrease the calories you burn by making you spontaneously move less and making you more efficiently with the same movements (4).

The good news is NEAT is largely controllable. You can actively walk more to make up for the lost energy expenditure along with strength training showing the ability to increase NEAT to an extent (13,14).

In fact, strength training is stupidly powerful. It reduces work efficiency in weight losers or non-weight losers (13). In fact, adaptive thermogenesis may only be relevant because studies look at a bunch of weight losers who don’t consistently lift.

Fortunately, science gives us more good news. The disproportionate drop in NEAT is usually only around 10-15% at most (7). It’s not very significant and does not doom you to regain fat even if it persists, especially considering adaptive thermogenesis also boosts NEAT when you overeat (21,25,26). Thus, bulking can be a good solution for adaptive thermogenesis.

Furthermore, when weight loss plateaus are analyzed in studies down to mathmatical model, plateaus are rarely due to adaptive thermogenesis, but rather a lack of adherence (31).

For most people mitigating adaptive thermogenesis in order to maintain the same bodyweight can be done by simply maintaining a high step count or walking your dog a little bit longer each day (29).

If you want even more good news, the small disproportionate drop in NEAT does persist for some time in some studies, but in other studies also completely recovers after about a year even without gaining weight (15,26).

So the term metabolic damage is complete myth. A more accurate description is simply your body unconsciously moving a bit less and being more efficient with energy until you decide to bulk.

Starvation mode is the idea that if you eat too little, your body goes into this mode where it senses starvation and hangs onto all your fat, refusing to lose anything.

According to these people, eating too little is either preventing weight loss or causing weight gain, so you have to eat more to get out of this so-called starvation mode to start losing weight again.

In some scenarios, eating more can be helpful for other reasons like giving you energy to exercise, but eating more on it’s own will never cause weight loss if you’re plateaued.

This physiologically just doesn’t happen! To put it bluntly, starvation mode is just another complete myth.

It’s impossible to eat too little to where you can’t lose weight. Here’s why.

As we discussed earlier, adaptive thermogenesis doesn’t make further weight loss impossible, just slightly harder.

If you’re not losing weight for long periods of time, it’s not because you eat too little. It’s ultimately because you’re still eating too much relative to your new weight and body composition.

Thinking you should eat more food so you can lose weight is like having too much toothpaste on your toothbrush and thinking adding more toothpaste will reduce the amount on the brush. It simply doesn’t make sense.

But you still might be thinking, “I eat so freaking little bro and can’t lose any more weight! Starvation mode must be real!”

The issue is most people who think they eat very little are actually still eating more than they think or they do eat very little, but very inconsistently.

This study for example, showed people underreport their caloric intake by about 47% (16). That’s massive! And keep in mind this is in people who were instructed to track their calories.

If you’re not even tracking, you can’t say you’re consistently eating too little because you have no tangible proof. Science consistently shows even if you do track, people generally underreport when left to their own free will, either on purpose or on accident.

As humans, we also tend to highlight the sacrifices we made and downplay our mistakes. We step on the scale, see that our plateau is still here, and then get super frustrated because we think we’ve sacrificed so much by eating so little.

However in reality we tend to forget all the days we ate in excess or the days where we didn’t track our calories accurately that would offset any deficit we thought we created.

When people truly eat too little consistently, weight loss always occurs, not plateaus where your body hangs on to weight. This is seen consistently in controlled studies and real-life examples.

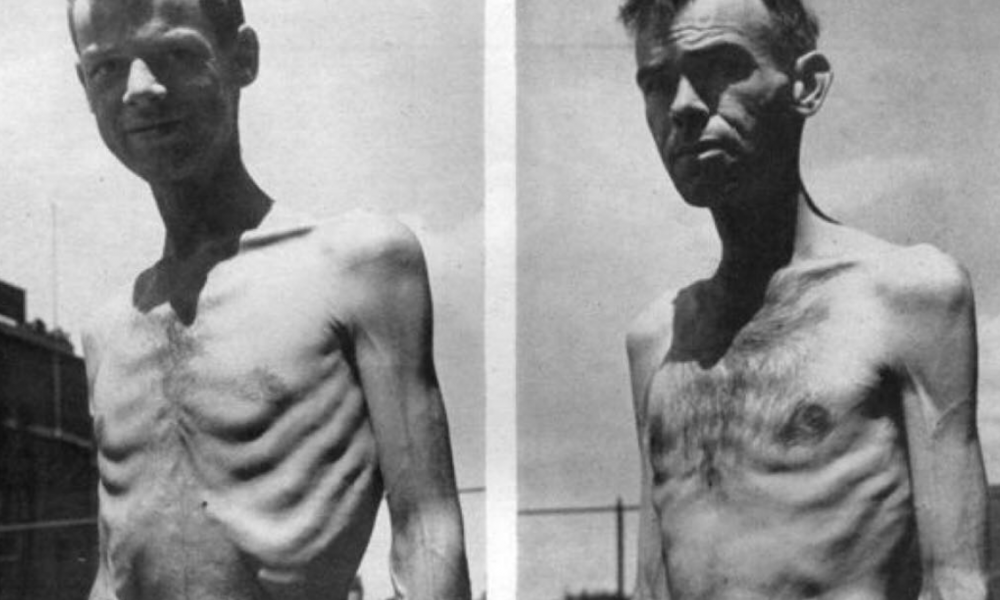

Back before rules and regulations were a thing, researchers conducted one extreme case study that would be illegal today called the Minnesota Starvation experiment where they starved the subjects (some of them pictured below). As you can see participants lost weight (a lot) instead of going into the fairytale that is starvation mode (17).

Then there’s more recent research. One study compared a group who ate in a 25% deficit to a group who ate strictly 890 calories a day. Both groups lost weight with the 890 calorie group losing more (18).

Other controlled research shows the same thing. If you truly eat very little consistently, starvation mode doesn’t happen, a lot of weight loss happens (19,20).

Some real world examples tell us starvation mode is bogus as well.

Christian Bale for instance had many dramatic transformations. To play a psychopath factory worker, he ate a diet of black coffee, a can of tuna, and an apple each day. If starvation mode was real, eating that little would prevent him from losing weight or even have him gain weight. But he didn’t, he lost a third of his bodyweight and looked like a skeleton.

Furthermore, in deserted island shows like Survivor where high calorie foods or food in general is scarce, people don’t plateau in weight or gain weight because of starvation mode, they lose weight.

And lastly, if you look at very extreme and deeply unfortunate examples where populations eat dangerously little like in anorexic patients and internment camp prisoners, starvation mode is nowhere to prevent weight loss (11).

Starvation mode doesn’t exist. If you think it does, you’re likely just not tracking calories consistently or accurately enough to know you’re still eating too much. If you truly ate low enough to be in a deficit consistently, weight loss must happen.

That was definitely a handful to get through with a lot of hard truths, but congratulations. You’re going to be better after learning this and stand exceedingly more informed than the average person who still believes in the myth of metabolic damage and starvation mode.

Here are some charming bullet points to sum it all up:

Ostendorf DM;Caldwell AE;Creasy SA;Pan Z;Lyden K;Bergouignan A;MacLean PS;Wyatt HR;Hill JO;Melanson EL;Catenacci VA; “Physical Activity Energy Expenditure and Total Daily Energy Expenditure in Successful Weight Loss Maintainers.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30801984/.

Fothergill E;Guo J;Howard L;Kerns JC;Knuth ND;Brychta R;Chen KY;Skarulis MC;Walter M;Walter PJ;Hall KD; “Persistent Metabolic Adaptation 6 Years After ‘The Biggest Loser’ Competition.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27136388/.

Martins, Catia, et al. “Metabolic Adaptation Is Not a Major Barrier to Weight-Loss Maintenance.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 9 May 2020, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/doi/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa086/5835207.

Reinhardt, Martin, et al. “A Human Thrifty Phenotype Associated With Less Weight Loss During Caloric Restriction.” Diabetes, American Diabetes Association, Aug. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4512223/.

Martins, Catia, et al. “Metabolic Adaptation Is an Illusion, Only Present When Participants Are in Negative Energy Balance.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 25 Aug. 2020, academic.oup.com/ajcn/advance-article/doi/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa220/5897225.

Kerns, Jennifer C, et al. “Increased Physical Activity Associated with Less Weight Regain Six Years After ‘The Biggest Loser’ Competition.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, Nov. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5757520/.

Mason C;Foster-Schubert KE;Imayama I;Xiao L;Kong A;Campbell KL;Duggan CR;Wang CY;Alfano CM;Ulrich CM;Blackburn GL;McTiernan A; “History of Weight Cycling Does Not Impede Future Weight Loss or Metabolic Improvements in Postmenopausal Women.” Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22898251/.

Thomas, Diana M, et al. “Effect of Dietary Adherence on the Body Weight Plateau: a Mathematical Model Incorporating Intermittent Compliance with Energy Intake Prescription.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, American Society for Nutrition, Sept. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4135489/.

Grab my free checklist on how to defeat your worst food cravings

Hey ladies, you have so much going for you, but if I’m being honest, many of you avoid lifting weights to your detriment.

All you want in life is to see the scale go down and the fat hanging off your waist vanish into thin air.

When somebody claims organic food to be better, that’s a good sign they are clueless about nutrition science and get their nutrition information from dorks on social media.