Which Makes You Fatter? Carbs or Fat?

Which Makes You Fatter? Carbs or Fat? When it comes to the three macronutrients, protein is like the golden child. It’s the one that does

Have you heard of reverse dieting? If you haven’t, don’t look it up because there’s an endless stream of YouTube videos and articles regurgitating this nonsense.

For those who don’t know what reverse dieting is, here’s a somewhat official definition from a prominent reverse dieting advocate: “A strategy of dieting where calories are increased in a controlled manner over time to increase metabolic rate while minimizing body fat gain.”

This is usually done with a slow increase in calories post diet. The benefits sound dreamy don’t they? Increasing your metabolism while minimizing fat gain. Where do I sign up?

Unfortunately, reverse dieting isn’t all it’s cracked up to be and arguably a deeply detrimental concept.

Reverse dieting is the girl that looks hot and smiles sweetly, but after getting to know her, you realize she’s has more red flags than a Chinese parade.

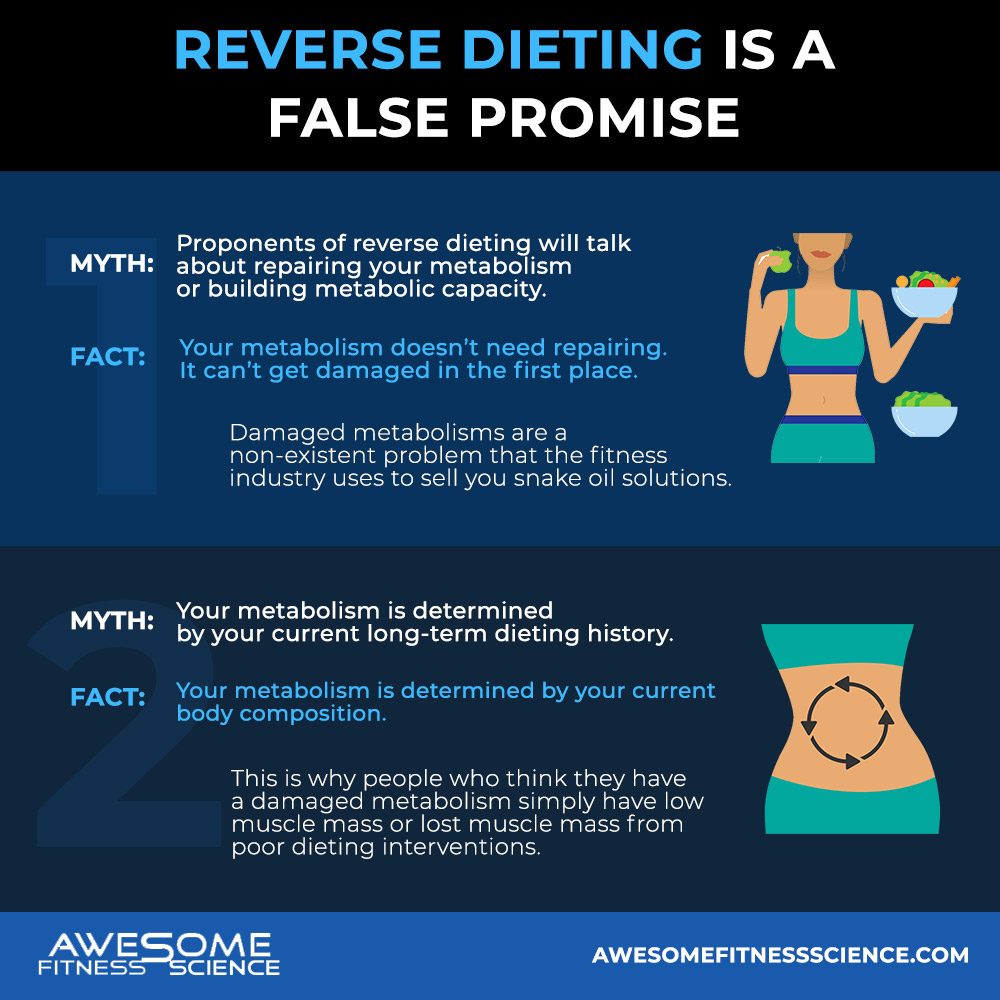

Proponents of reverse dieting will talk about repairing your metabolism or building metabolic capacity.

However, your metabolism doesn’t need repairing. It can’t get damaged in the first place (12). Damaged metabolisms are a non-existent problem that the fitness industry uses to sell you snake oil solutions.

Furthermore, building metabolic capacity is bull shenanigans. Your metabolism is determined by your current body composition not your long-term dieting history (1,10,12-15). This is why people who think they have a damaged metabolism simply have low muscle mass or lost muscle mass from poor dieting interventions (2).

But regardless, if you end up at the same body composition, your metabolism is the same whether you got there quickly or slowly (3). So you’re not actually getting a greater bang for your buck by returning to maintenance slowly with reverse dieting.

In fact, it’s counter intuitive because the more time you spend in a deficit and away from maintenance, the lower your protein balance delaying your ability to build back lost muscle or construct new muscle tissue efficiently (4-7).

Simply put, there’s no metabolic advantage to reverse dieting because no physiological mechanism exists.

Anyone who claims to maintain on higher calories after reverse dieting simply gained weight/muscle which allows them to train more/harder while getting an increase in NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis). This can all be done sooner from swiftly increasing calories to maintenance instead of reverse dieting because energy expenditure doesn’t recover until you exit the deficit.

For further perspective, remember my refeed article? I highlighted research that finds massive overfeeding barely increases your metabolism. There’s no way someone can increase their metabolism from small deposits of calories while taking longer to exit their deficit (compromised state).

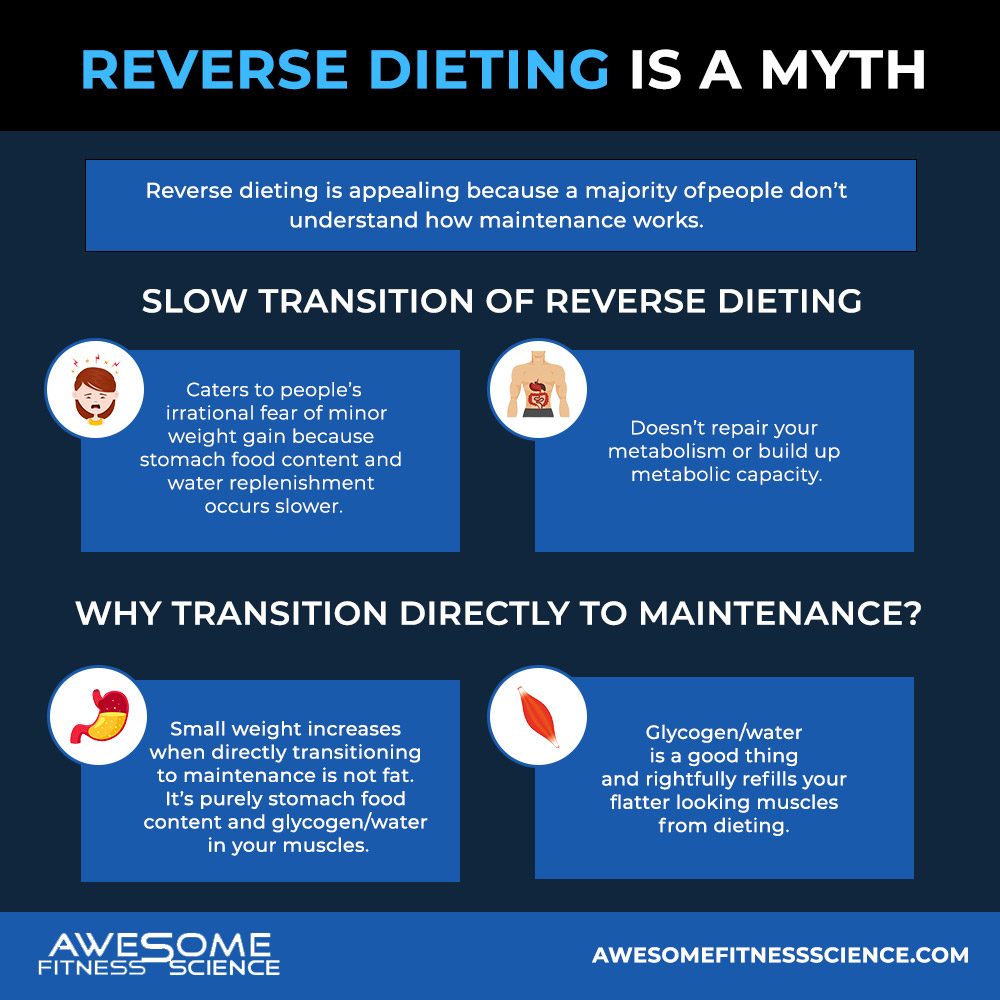

To make a long story short, reverse dieting doesn’t repair your metabolism or build up metabolic capacity.

Reverse dieting is appealing because a majority of people don’t understand how maintenance works. I don’t blame them because most people barely understand how dieting works, let alone what it means to finally transition to maintenance.

You see, when you diet, you’re in a caloric deficit which means energy is being lost via fat mass. Most people understand that much, but a caloric deficit also means your energy replenishment in glycogen stores are incomplete (8).

Your glycogen stores are essentially the sugar/water within your muscles that make them look full and help them perform. Why is this relevant?

Well, when you go from a deficit to maintenance, there will likely be a small weight increase. Most people’s paranoid minds think this is fat, but it is not. Let’s say you even overestimate your maintenance by 300 whopping calories per day. It would still take close to 2 weeks to even gain 1 pound of fat assuming all those calories get stored as pure fat.

So the small bump in weight when you transition directly to maintenance is purely glycogen/water in your muscles. It’s a good thing and rightfully refills your flatter looking muscles from dieting. If you transition correctly (which I’ll outline in another article), you’re maintaining the same body composition.

There is no fat gain. Your weight will stabilize once water balance reestablishes itself at your new caloric intake which should take a week at most.

But what I just explained is not common knowledge, thus people buy into the fairy tale of reverse dieting because they’re neurotic about the initial scale spike post-diet.

The slow transition of reverse dieting caters to this irrational fear because stomach food content and water replenishment occur more gradually.

But objectively speaking, slower transitions to maintenances are at best a waste of time and at worse a slower recovery from the diet.

When clients insist on reverse dieting, I explain to them if we reverse diet, they’re essentially paying me to prolong time. I’d rather use that time to teach them how to maintain their post diet weight or bulk in a surplus.

Some coaches throw out the idea to reverse diet physique competitors. This makes me want to roll my eyes so many times over, my optic nerve would get tangled. Competitors shouldn’t even consider reverse dieting.

With competitors, they are dieting to extreme, unsustainable, and arguably dangerous levels of leanness. The changes to their physiology is deeply unfavorable which is why no human can sustain extreme leanness healthily.

Post show, they not only have to transition to maintenance, but should ideally enter a surplus as soon as possible to regain essential fat and lost muscle to return to a healthy state.

2017 data in competitors found a fast reasonable bump in calories recovered their metabolism in 1 week (9). Even then, Male testosterone didn’t fully recover till 4-6 weeks, so imagine how much worse it’d be if you reverse dieted back up slowly. You’d have the sex drive of a robotic nun for months.

Another study looked at female competitors who took 2 months to recover baseline bodyweight (10). Despite having more muscle compared to their pre-show baseline, their concentric/eccentric force did not fully recover. This supports a faster return up to maintenance/surplus. More food essentially means better exercise performance, not to mention a healthier menstrual cycle recovery for females (11,16).

Regardless if you compete or not, once you finish a diet, a faster jump to maintenance gives you more fuel to train harder and makes you feel less deprived. With reverse dieting, you’re dorking around up to maintenance slowly with no benefit.

Imagine this. You finish your diet and look eye catchingly lean. Your girlfriend says, “Yo, let’s celebrate and get some happy hour food tonight!”

If you believed in the nonsense of reverse dieting, you’d have to look her dead in the eyes and say, “Sorry babe, those foods still don’t fit my macros. I can only bump up my calories by 12 grams of carbs this week. We can celebrate in a few weeks or months once my calories are reasonably higher though.”

Congratulations dummy. You declined your girlfriend’s awesome happy hour offer while doing something completely unnecessary, time-consuming, and counterproductive to your long-term body composition goals.

Fortunately, that won’t happen to you because you now know better. However, not everyone knows better, so if you don’t mind, please share this article to make this world a better place. And by a better place, I’m describing a world void of reverse dieting.

1. Ostendorf, Danielle M, et al. “No Consistent Evidence of a Disproportionately Low Resting Energy Expenditure in Long-Term Successful Weight-Loss Maintainers.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 12 Oct. 2018, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/108/4/658/5129189?login=true.

2. Dulloo, A. G., et al. “How Dieting Makes the Lean Fatter: from a Perspective of Body Composition Autoregulation through Adipostats and Proteinstats Awaiting Discovery.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 22 Jan. 2015, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/obr.12253.

3. Hintze . “The Rate of Weight Loss Does Not Affect Resting Energy Expenditure and Appetite Sensations Differently in Women Living with Overweight and Obesity.” Physiology & Behavior, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30496740/.

4. Pasiakos . “Acute Energy Deprivation Affects Skeletal Muscle Protein Synthesis and Associated Intracellular Signaling Proteins in Physically Active Adults.” The Journal of Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20164371/.

5. Areta . “Reduced Resting Skeletal Muscle Protein Synthesis Is Rescued by Resistance Exercise and Protein Ingestion Following Short-Term Energy Deficit.” American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24595305/.

6. Carbone . “Effects of Short-Term Energy Deficit on Muscle Protein Breakdown and Intramuscular Proteolysis in Normal-Weight Young Adults.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition Et Metabolisme, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24945715/.

7. Murphy, Chaise, and Karsten Koehler. “Caloric Restriction Induces Anabolic Resistance to Resistance Exercise.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 31 Mar. 2020, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-020-04354-0.

8. Murray, Bob, and Christine Rosenbloom. “Fundamentals of Glycogen Metabolism for Coaches and Athletes.” Nutrition Reviews, Oxford University Press, 1 Apr. 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6019055/.

9. AE;, Trexler. “Physiological Changes Following Competition in Male and Female Physique Athletes: A Pilot Study.” International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28422530/.

10. Tinsley . “Changes in Body Composition and Neuromuscular Performance Through Preparation, 2 Competitions, and a Recovery Period in an Experienced Female Physique Athlete.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30036283/.

11. Bonilla, Diego A, et al. “The 4R’s Framework of Nutritional Strategies for Post-Exercise Recovery: A Review with Emphasis on New Generation of Carbohydrates.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, MDPI, 25 Dec. 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7796021/.

12. Mason . “History of Weight Cycling Does Not Impede Future Weight Loss or Metabolic Improvements in Postmenopausal Women.” Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22898251/.

13. TN;, Sathyaprabha. “Basal Metabolic Rate and Body Composition in Elderly Indian Males.” Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10846632/.

14. Lazzer . “Relationship between Basal Metabolic Rate, Gender, Age, and Body Composition in 8,780 White Obese Subjects.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19478787/.

15. Johnstone . “Factors Influencing Variation in Basal Metabolic Rate Include Fat-Free Mass, Fat Mass, Age, and Circulating Thyroxine but Not Sex, Circulating Leptin, or Triiodothyronine.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16280423/.

16. De Souza MJ. “Randomised Controlled Trial of the Effects of Increased Energy Intake On MENSTRUAL Recovery in EXERCISING Women with MENSTRUAL Disturbances: The ‘REFUEL’ Study.” Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34164675/.

Sign up for AwesomeFitnessScience Weekly. You’ll get juicy insider secrets, updates, and stories.

Which Makes You Fatter? Carbs or Fat? When it comes to the three macronutrients, protein is like the golden child. It’s the one that does

One of the biggest barriers to improving your health/fitness is social pressure. In fact, for many people, it’s the biggest thorn.

The Lifter’s Guide to Warming Up Warming up is like saving for retirement. We all know it’s important, but we don’t exactly know why or