Training to Failure – Optimal or Overrated?

Training to Failure – Optimal or Overrated? The training to failure debate rages on as bros, lifting nerds, and coaches just can’t seem to agree

So you want to build muscle, lose 30 pounds of fat, and fit into a size whatever right? That’s cute and all, but goal setting alone don’t mean much. After all, winners and losers have the same goals. Everybody aims to be successful and healthy, but not everybody actually does it.

What really matters is your behavior. Your behavior is the bridge between where your intentions and the results you’re after. Unfortunately, behavior change is hard. Some humans spend a lifetime trying to break bad habits while starting better ones.

So let’s go over everything you need to know about changing your behaviors, so you can essentially accomplish world domination.

One of my favorite quotes is “Your current results are the product of your current habits.” What you consistently do drives you towards a trajectory. Piling your face with donuts while remaining sedentary daily drives you towards a path of disease and an early death. Forgive my bluntness. Sorry not, sorry.

But contrastingly, eating a mostly healthy diet and exercising daily often drives you towards a healthier and longer life.

In other words, habits are deeply vital whether small or big.

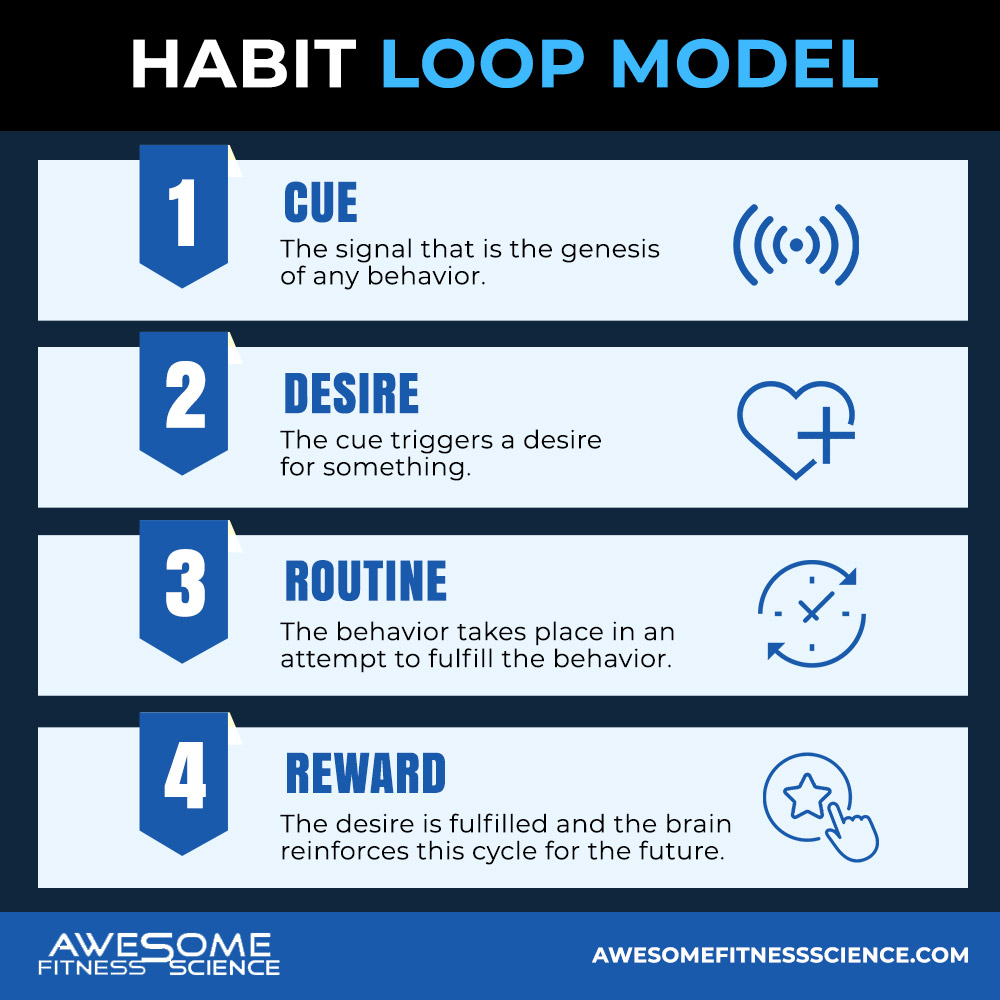

So before we can learn the nuances of behavior change, let’s learn the model of habits. Here’s how habits are born and repeated (1). This is called the habit loop.

So here’s a couple examples, that I see all too common.

Example 2:

As you repeat habits, they get more ingrained into your life. If you feel like your habits suck. I’ll show you how to change them in a sec. But first, let’s talk about your identity.

Grab my Free Lifter’s Guide to Managing Stress

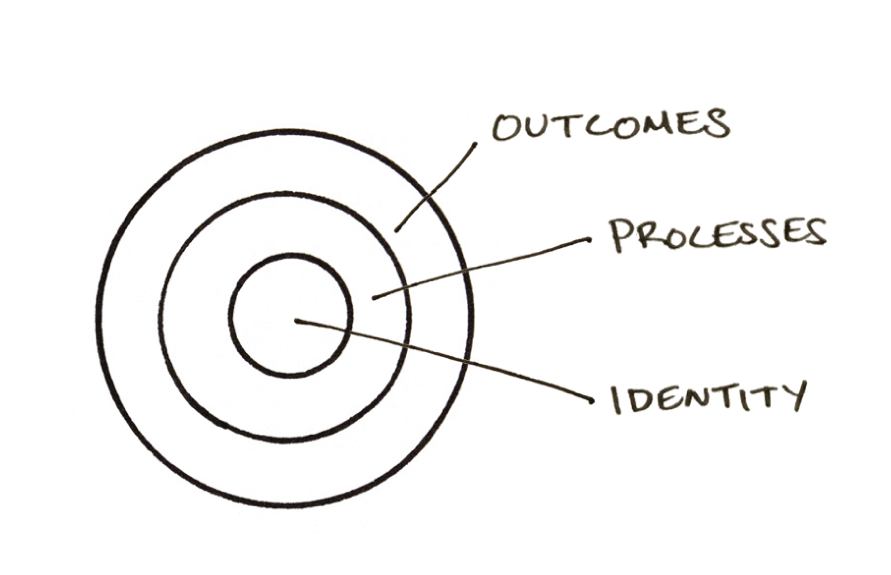

Most people overly focus on outcomes or what they want to achieve. This causes you to lose sight of the process and ultimately, the outcome never arrives (4). Instead, to achieve your desired outcome, you should focus on the process of behavior change and this process is rooted in your identity. Simply put, your identity will shape your behavior and your behaviors will produce the results you want. Pretty magical huh?

To do this, James Clear (behavior change expert who’s book helped me write this article) explains this simply. “Decide who you want to be and prove it to yourself with small wins.”

You might not fully believe that you’re sober person, a fit mom, or a responsible adult who gets 8 hours of sleep just yet. That’s ok. As your behaviors shift, they will help you believe that you are a new person.

Identifying with a new identity is also better than identifying with goals because most people set utterly unrealistic goal, especially with weight loss (6,7,8).

Furthermore, how ambitious your goals are has no relation to how well you’ll execute them and in some cases ambitious goals make you more unsuccessful (9,10,11).

So ultimately, you must approach behavior change with the intent that you will become a new person (ideally with no deadline) or else the behavior won’t develop and stick (2). Once your identity and behaviors are locked in though, the outcome becomes inevitable.

For example, fitness enthusiasts rarely skip the gym. They get their workouts in even on most vacations despite not always feeling like it. The behavior gets consistently done because it’s part of their identity.

This is why it’s hilarious when I hear non-fitnessy people say they wish they had this abundant drive I have to workout. In reality, I don’t have much more motivation to workout than they do. Exercising still sucks and I’d rather watch Netflix, but I exercise because the behavior lines up with who I identify to be (an exerciser) on every week of the year.

So establish the type of person you want to become forever. Once you do that, it’s time to manipulate the habit loop to change your behaviors which proves the metamorphosis taking place, thus eventually yielding the results you want (3).

When approaching habit change, a common mistake people make is trying to stop bad habits, like abstaining from certain foods, cutting out alcohol, or avoiding xyz. That’s fine, but research finds starting good habits is generally easier and more successful than stopping bad ones (3).

For example, adding in more lower calorie foods like fruits and vegetables produces better behavior and fat loss outcome results than trying to cut out high calorie foods (5). So if you’re new to behavior change, do yourself a favor and focus on adding good habits before cutting bad ones.

To form good habits, you can manipulate aspects of the habit loop by doing the following:

Conversely, to break bad habits, you will manipulate the aspects of the habit loop by doing the following:

Making things more obvious means making it more concrete. I’ll start working out next week is beyond vague. You say that, but it doesn’t happen. Even if you get a bit more specific like I’ll start working out Monday, that doesn’t change much. Monday comes around and you delay it every Monday until you realize you can’t walk up your apartment without having a borderline heart attack.

Instead, try something more along the lines of I will block off exactly 80 minutes in my calendar after work to drive my car to the gym and lift weights for 60 minutes.

So having a specific plan to follow up your intentions is key to making habits more obvious (12,13). This is also called implementation intentions. Instead of just saying I plan to do xyz, you say I will implement xyz behavior at xyz time at xyz place.

Specificity holds you accountable and gives you a cue to trigger a new habit loop.

Here are some examples of implementation intentions:

Furthermore, to make your habit more obvious, you can manipulate your environment. Setting up your workout clothes the night before so it’s the first thing you see each morning will not only trigger the cue of working out, but it makes it easier.

If you want to eat more fruits and vegetables, you can make them more visible by having them on the counter or bringing them to the front of the fridge.

Similarly, you can starve bad habits by changing the environment so the cue never triggers the habit loop.

If having nuts at your desk triggers you to start snacking, place the nuts out of sight. If you stay up stalking your ex instead of getting your beauty rest, you can charge your phone outside of your room.

In fact, studies that manipulate environment alone can birth ideal habits while discouraging undesirable habits without the participants even knowing it (14).

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. As the beholder, you have to be attracted to good habits or unattracted to bad habits.

For example, exercise is a habit everyone knows they should be doing, but most Americans ignore exercising because exercise is not attractive especially relative to the level of sacrifice.

With exercise, you invest a noticeable amount of time, energy, discomfort, inconvenience, effort, and in some cases, money. Your immediate return is nothing noticeable. The noticeable physique results of exercise take forever even if you pay for personal trainers and fancy gyms. You’ll never get noticeable results after 1 workout, not even a few workouts. And despite your health improving immediately from exercise, that’s not a relevant enough benefit for people (even if they say it is).

Inevitably people give up because the behavior is no longer attractive to them. However, that’s only the case if you solely think of what exercise can do for you immediately.

You need to shift your motivation from extrinsic to intrinsic. In other words, you need to stop being attracted so much by the immediate exterior results and be more attracted to the internal aspects.

Developing an intrinsic motivation comes down to 3 things, competence, relatedness, and autonomy.

This is how you make good habits like exercising appear more attractive.

For breaking bad habits, to make them unattractive, you have to replace them with an alternative that fulfills a similar desire.

For example, you might drink alcohol when you’re lonely. Instead set an implementation intention to call a friend when you’re feeling lonely.

Or you might like how your brain enjoys full fat ice cream after dinner. Instead, set a new habit to have yogurt or low fat/high protein ice cream instead.

It might not satisfy you the same way, but it satisfies you enough that the full fat ice cream loses it’s attraction.

Furthermore, tracking the effects of neglecting the bad habit is great because it keeps you accountable and makes not doing the former habit more appealing.

For instance, a guy who’s trying to quit smoking might keep a weekly self-report of the following to remind him of the attractive benefits of not smoking (20):

Your environment and preparation make good habits easier. Meal prepping sounds like some daunting overwhelming task, yet it actually saves you time in the long run and sets you up for success (21,22).

Think about it. You can spend 2 hours a week to cook and have a guaranteed success plan making it easy to grab exactly what you intend to eat. Or you can spend an hour each night freaking out, trying to come up with some healthy last minute dinner just to regrettably end up in a fast food drive thru again.

Another key to making good habits easier is habit stacking. This is similar to implementation intention, but instead of attaching the habit to a newly formed cue, you simply stack your desired the habit onto an existing habit. The existing habit can now act as the cue.

By adding to your current routine, the new habit is more likely to stick (23,24,25).

For example, if you want to start reading more, you can plan to read for 5 minutes after you brush your teeth.

If you want to consume more protein, you can add a protein shake to your typical morning coffee routine.

Furthermore, making habits easier is all about starting small. I’m talking about stupid small. The reason most people never get anywhere in life is because they’re always aiming for massive steps that they can’t accomplish.

Like, I hate to break it to you, but you’re not amazing enough to go from couch potato to exercising for 60 minutes every day. But if you start with exercising 3 times per week for 40 minutes per workout, that’s much more doable.

You’ll get the habit loop going and adding more becomes easier later.

Same thing with breaking bad habits. Let’s say you’re trying to cut back on spending. If you’re used to buying a latte daily, cutting that cold turkey won’t be very fun. You’ll give up after a week and be back to square one. But it’s much more doable to start by cutting back a latte or two each week.

You and I love to feel good; I mean who doesn’t right? We all crave the dopamine response that comes at the end of every habit loop. We want to experience that pleasure right away, especially considering humans are notoriously bad at delaying gratification.

Consequently, your brain remembers what’s rewarding. To get the same reward response it craves, it will go through the habit loop that resulted in that reward. What can you learn from this dynamic?

In the words of James Clear, the cardinal rule of behavior change is as follows: “What is immediately rewarded is repeated. What is immediately punished is avoided.”

So the first step to manipulating our reward system in our favor is self-report. You have to track the habit because it reinforces the habit loop each time you check a box on the calendar for sticking to a desired habit (or avoid an undesirable habit).

Like I mentioned earlier, you simply need a way to tell yourself, I got a small win today. I can keep doing this until the long-term benefits of the habit become my reward.

If you find yourself unable to stick to a new habit despite this, you can increase the immediate reward response by adding incentives. For example, for every cup of vegetables you eat, you can put a dollar towards a jar or savings account dedicated to a future vacation, a new car, or that designer purse you’ve been eyeing.

You can do this with breaking bad habits too. For example, for every night you go without drinking or smoking, you can do the money jar thing as well. This makes abstaining more satisfying.

You can also make the unwanted habit less satisfying with accountability and reverse bets. With accountability, you have someone keep close tabs on you who you highly look up to. Because you don’t want to let them down, the bad habit becomes less satisfying because it makes you look bad.

For example, I know a guy who hasn’t watched porn in over a decade because his computer has a software that notifies me if he does. Suddenly, watching unrealistic sex scenes on the internet is now less rewarding to his brain.

You can also utilize reverse bets which are essentially bets against yourself. You hand a friend an envelope of money and you tell them to donate the money in your name to a political cause or sports team you oppose if you slip up on certain habits. It doesn’t have to be this extreme, but this is a highly effective method.

I used reverse bets to pretty much terminate my awful habit of napping by committing to donate to some vegan organization if I took more than one nap per week. To clarify, napping isn’t bad, but for me, I was napping for too long and too frequently which murdered my sleep/productivity.

Essentially, doing anything you want or abstaining from anything comes down to manipulating the habit loop model enough until your new behavior takes a life of it’s own and embeds itself into your chosen identity. Research finds it can take a few weeks up to a few years for a habit to be locked in (26).

No worries though, as you apply more of these strategies, you’re stacking the deck in your favor and proving to your brain that you’re a new person as the behavior becomes more consistent.

So there is plenty of truth to the mantra, “Fake it until you make it.” However, a better one to live by is, “Be it until you see it.”

If you have further questions, don’t hesitate to email me ([email protected])

1.

Gardner, Benjamin, et al. “Making Health Habitual: the

Psychology of ‘Habit-Formation’ and General Practice.” The British Journal

of General Practice : the Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners,

Royal College of General Practitioners, Dec. 2012,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3505409/.

2.

Verplanken, Bas, and Jie Sui. “Habit and Identity:

Behavioral, Cognitive, Affective, and Motivational Facets of an Integrated

Self.” Frontiers in Psychology, Frontiers Media S.A., 10 July 2019,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6635880/.

3.

A;, Oscarsson. “A Large-Scale Experiment on New Year’s

Resolutions: Approach-Oriented Goals Are More Successful than

Avoidance-Oriented Goals.” PloS One, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33296385/.

4.

Fishbach, Ayelet, and Jinhee Choi. “When Thinking about

Goals Undermines Goal Pursuit.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, Academic Press, 22 Mar. 2012,

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749597812000222?via%3Dihub.

5.

Vadiveloo, M, et al. “Increasing Low-Energy-Dense Foods

and Decreasing High-Energy-Dense Foods Differently Influence Weight Loss Trial

Outcomes.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 7 Dec. 2017,

www.nature.com/articles/ijo2017303.

6.

CS;, Grant. “Clarifying Achievement Goals and Their

Impact.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, U.S. National

Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14498789/.

7.

G;, Foster. “What Is a Reasonable Weight Loss?

Patients’ Expectations and Evaluations of Obesity Treatment Outcomes.” Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9103737/.

8.

Linde . “Weight Loss Goals and Treatment Outcomes among

Overweight Men and Women Enrolled in a Weight Loss Trial.” International

Journal of Obesity (2005), U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15917847/.

9.

Durant, N H, et al. “Empirical Evidence Does Not

Support an Association between Less Ambitious Pre-Treatment Goals and Better

Treatment Outcomes: a Meta-Analysis.” Obesity Reviews : an Official Journal

of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, U.S. National

Library of Medicine, July 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4366879/.

10. Dalle

. “Weight Loss Expectations in Obese Patients and Treatment Attrition: an

Observational Multicenter Study.” Obesity Research, U.S. National

Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16339128/.

11. Grave,

Riccardo Dalle, et al. “Weight Loss Expectations in Obese Patients and

Treatment Attrition: An Observational Multicenter Study.” Wiley Online

Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 6 Sept. 2012, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1038/oby.2005.241.

12. Gollwitzer,

Peter M., and Paschal Sheeran. “Implementation Intentions and Goal Achievement:

A Meta‐Analysis of Effects and Processes.” Advances in Experimental Social

Psychology, Academic Press, 7 May 2006, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065260106380021.

13. P;,

Milne. “Combining Motivational and Volitional Interventions to Promote Exercise

Participation: Protection Motivation Theory and Implementation Intentions.” British

Journal of Health Psychology, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14596707/.

14. Thorndike,

Anne N., et al. “A 2-Phase Labeling and Choice Architecture Intervention to

Improve Healthy Food and Beverage Choices.” American Journal of Public

Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3329221/.

15. “APA

PsycNet.” American Psychological Association, American Psychological

Association, psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-97029-002.

16. EL;,

Ryan. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation,

Social Development, and Well-Being.” The American Psychologist, U.S.

National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11392867/.

17. Christopher,

Richard. “Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness in the Classroom: Applying

Self-Determination Theory to Educational Practice – Christopher P. Niemiec,

Richard M. Ryan, 2009.” SAGE Journals,

journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1477878509104318.

18. Ruzek,

Erik A., et al. “How Teacher Emotional Support Motivates Students: The

Mediating Roles of Perceived Peer Relatedness, Autonomy Support, and

Competence.” Learning and Instruction, Pergamon, 29 Jan. 2016,

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959475216300044.

19. Wang,

C.K.John, et al. “Competence, Autonomy, and Relatedness in the Classroom: Understanding

Students’ Motivational Processes Using the Self-Determination Theory.” Heliyon,

Elsevier, 19 July 2019,

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S240584401935604X.

20. Gardner,

Benjamin, et al. “Towards Parsimony in Habit Measurement: Testing the Convergent

and Predictive Validity of an Automaticity Subscale of the Self-Report Habit

Index.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity,

BioMed Central, 30 Aug. 2012,

ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1479-5868-9-102.

21. Ducrot,

Pauline, et al. “Meal Planning Is Associated with Food Variety, Diet Quality

and Body Weight Status in a Large Sample of French Adults.” The

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, BioMed

Central, 2 Feb. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5288891/.

22. Monsivais,

Pablo, et al. “Time Spent on Home Food Preparation and Indicators of Healthy

Eating.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, U.S. National Library

of Medicine, Dec. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4254327/.

23. Arlinghaus,

Katherine R, and Craig A Johnston. “The Importance of Creating Habits and

Routine.” American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, SAGE Publications, 29

Dec. 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6378489/.

24. Smith,

Kyle S, and Ann M Graybiel. “Habit Formation.” Dialogues in Clinical

Neuroscience, Les Laboratoires Servier, Mar. 2016,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4826769/.

25. Fritz

. “Intervention to Modify Habits: A Scoping Review.” OTJR : Occupation,

Participation and Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31642394/.

26. Lally,

Phillippa, et al. “How Are Habits Formed: Modelling Habit Formation in the Real

World.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 16 July 2009,

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ejsp.674.

Sign up for AwesomeFitnessScience Weekly. You’ll get juicy insider secrets, updates, and stories.

Training to Failure – Optimal or Overrated? The training to failure debate rages on as bros, lifting nerds, and coaches just can’t seem to agree

How Much Does Alcohol Interfere with Being Hot and Healthy? If there’s one thing people love, it’s alcohol. You want to drink it, but also

So you want to build muscle, lose 30 pounds of fat, and fit into a size whatever right? That’s cute and all, but intentions alone won’t help you reach your goals.