The Definitive Detoxing Guide for Dummies

Detoxing is the latest buzzword and everyone thinks they need to detox. However, nobody knows what they’re detoxing from, what detoxing accomplishes, and to how to go about it.

Refeeds are essentially mini diet breaks (Read this diet break article first if you haven’t). However, instead of going to maintenance for weeks at a time, refeeds only last days. Some people also take refeeds into a surplus.

The general idea is that the quick boost in food will boost your metabolism, decrease your hunger/stress hormones, and retain a bit more muscle so you get better dieting results when you return to dieting.

How well does this play out though?

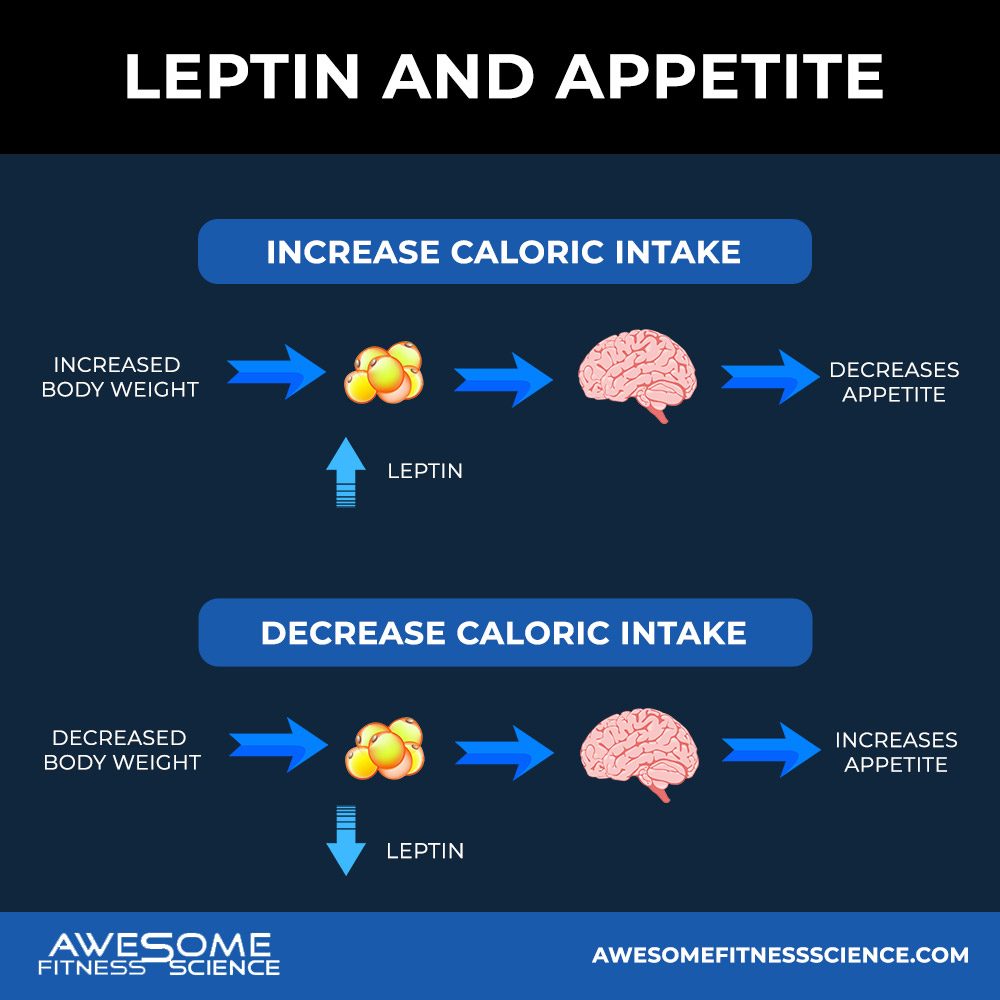

The proposed mechanism behind refeeds is leptin. Leptin is a hormone that regulates your appetite and energy expenditure. It gets released from fat cells, so the more fat you have, the more leptin you produce which equates to more calories burned and less hunger.

Carbohydrates tend to increase leptin more than fat, so refeeds and diet breaks are usually done by primarily increasing carbohydrate intake (36).

For example, Chin Chance et al found 3 days of overfeeding your maintenance by 30% increased leptin. However, when the participants lowered their energy intake, the increase disappeared (1).

So, your appetite doesn’t remain suppressed after a refeed is over because leptin will drop when you go back to a lower energy intake.

Body composition dictates leptin more than acute energy intake, so to get more leptin, you’d have to actually get fatter (2). Even in healthy individuals, a 50% surplus refeed day doesn’t cause them to eat less the next day (3). Leptin adapts too quickly, within 12 hours, so you can’t temporarily eat more food and trick your body into pumping out leptin long term (2,4). In other words, if you want extra fullness from not dieting, you have to restore your non-dieting body.

This is irrespective of the size of the refeed. Hulmi et al found female competitors who gained weight post-show couldn’t fully restore leptin until their fat mass was fully recovered even after taking a 17.5 week maintenance period (7).

Other research confirms this too. The only time people are able to spike leptin strong enough (+40%) to decrease food intake the following day is when participants ate 120 calories per kg of bodyweight (2). That means a 200-pound person would have to refeed with over 10,000 calories.

So the only way refeeds will even put a dent in the following day’s energy intake is by pigging out disproportionately where you’ll also gain noticeable fat overnight. Essentially, you’re taking 4-5 steps back to take 1 step forward.

Other research is even more grim. One study finds a 60% surplus day increases appetite in subsequent days not decreases it (5). This may be psychological, but that also speaks to a detriment of refeeds. The more calories you refeed, the harder it is to get back to dieting especially in beginner dieters. And the less calories you refeed, the less leptin spikes up.

Regardless, you waste extra days where you could’ve made more progress for a minimal leptin spike that disappears when returning to the diet.

It’s a lose-lose situation as far as appetite is concerned.

Some people propose that refeeds will boost your energy expenditure to help with dieting. We know that increasing food boosts your energy expenditure, but is the effects strong enough?

Most certainly not. If that were the case, we’d all be able to eat extra donuts every weekend and lose the same weight as someone who didn’t.

For example, Dirlewanger et al overfed healthy females 40% past their maintenance (6). This was an average of 670 calories. Their leptin levels only increased 28% and their energy expenditure only increased 7%. This leaves 530 calories to be stored, most of which will be fat tissue.

Simply put, you don’t enhance fat loss by eating more for a day. That’s like saying I’ll clean my garage faster tomorrow if I add more stuff to it today. Completely irrational.

Furthermore, McDevitt et al fed lean and obese individuals a 50% surplus for 4 days (8). This would be similar to a short vacation filled with splurging.

Energy Expenditure only increased 7.9%, so that leaves you in a net 42% surplus. It also found that fat balance was the same whether the participants were overfed with carb or fat.

Protein balance increased by 6-10 grams, so miniscule muscle growth likely occurred as expected with any overfeeding. Interestingly, the carb overfeeding group saw an initial drop in protein balance. This indicates if you do a typical refeed of carbs at maintenance for only a couple of days, you’re restoring some glycogen at best, but not gaining any muscle from the refeed.

This all lines up with adaptive thermogenesis research where the downregulation of your non-exercise activity doesn’t fully recover in some people even after a year of maintenance (9). What makes you think you can get some miraculous effects from a weekend refeed?

Refeeds have also been proposed to retain more muscle mass. From all the data I’ve discussed so far, this isn’t the case. At best, you’d reach the same body composition in a longer time frame.

But what if you match for the same time frame and simply adjusted the energy balance? This means you eat even less during your diet days to afford the additional refeed days.

Campbell et al did a study on this with a continuous dieting group against a refeed group who had 2 maintenance days (30). The study concluded the refeed group had better muscle retention, but the study had many flaws including the fact that the refeed group ate a higher average energy balance and overall adherence was poor.

Consequently, a new paper finalized those flaws and more (31). Campbell’s study also doesn’t line up with the rest of the literature and mechanistically, doesn’t make sense. Why would anyone eat even less for 5 days and think 2 maintenance days per week could increase their muscle balance?

The lower your acute energy balance, the worse your muscle balance will be because protein construction decreases while protein breakdown increases (32,33,34). Not to mention IGF-1, a potentially anabolic hormone decreases as well (35).

It’s simply wiser to stay closer to maintenance and diet on those calories continuously. You’ll have a better protein balance for muscle retention and it’s easier to program workouts to match a consistent calorie intake.

Some people do refeeds with the idea that it’ll reduce cortisol (stress hormone) and increase focus so they have less mental strain when returning to the diet.

However, the research disagrees strongly. For starters, fasting increases cortisol, but overall caloric restriction doesn’t, so despite popular belief, dieting isn’t as physiologically stressful as people claim (10). Even with intermittent fasting protocols, your next meal will normalize cortisol.

The only exception to this is male competitors dieting for contest preps. We have 2 case studies that highlights an increase in cortisol late in their prep. Keep in mind, this occurred in dudes who dieted for 6 months straight on poverty calories without a single slip up all the way down under 5% body fat (11,26).

This level extreme doesn’t apply to you.

Even in female competitors prepping for a show, there is no drop in cortisol from dieting (7).

This lines up with the rest of the literature showing cortisol has no change even during very low-calorie diets and sometimes even decreases with fat loss (12,13,14,15).

In fact, as long as your diet doesn’t impact your sleep or appetite, your caloric intake largely doesn’t matter (16).

The diet fatigue/stress that you’re trying to mitigate with refeeds doesn’t objectively exist. Don’t believe me? Look at more research.

Grab my Lifter’s Guide to Managing Stress

Wadden et al put obese subjects on either a 500 or 1200 calorie diet (17). Despite the 500-calorie group reporting more dizziness and fatigue, both groups rated the same for diet acceptability and disruptiveness. Psychological performance and hunger were the same between groups as well.

In essence, both groups had the same adherence and having higher calories merely increased comfort on a highly unrealistic study design.

In other studies, when the calories in food are unknowingly reduced even to astronomical levels, there is no difference in hunger, fullness, brain power, memory, mood, or reaction time in a variety of subjects (18,19,20).

Even in lean intense soldiers doing vigorous training, there was no difference in mood, mental performance, and reaction time (21).

Ramadan fasting also has no impact on brain function either (22).

Generally, it is around the 24-48 hour mark where symptoms of stress and anger arise (23,24,25). So sure, if you starve yourself and diet like an idiot on a stranded island, of course refeeds will help destress you.

But the idea of increased diet fatigue and stress from a realistic and controlled diet is unsupported. One systematic review found no correlation between energy intake and brain function (27). In fact, there was a trend that long-term dieting improves brain function because once your nutrition becomes a lifestyle, life gets easier.

The answer is quite interesting. It’s the initial adjustment to knowing you’re on a diet.

In a metabolic ward study where lean participants were forced to exercise and diet on a 40% deficit, they had a drop in mood for the first 3 weeks (28). Even with this huge deficit which would cause muscle loss, there was no further change in mood after 3 weeks. Brain function and sleep were fine the whole time also.

With more realistic protocols, it’s plausible to say your mood might dip for a week, maybe two at most. However, long term comfort won’t get better by taking a break or refeed. Your perceived stress only gets better with consistency because your attempted dieting behaviors needs to become your current lifestyle.

This is why dieting stress/fatigue is pretty massive myth. What you think is a spike in stress is temporary perceived discomfort of adjusting to dieting habits similar to adjusting to any lifestyle change (moving, new job, kids, climate, etc).

If you feel too stressed on your current diet, you either need to

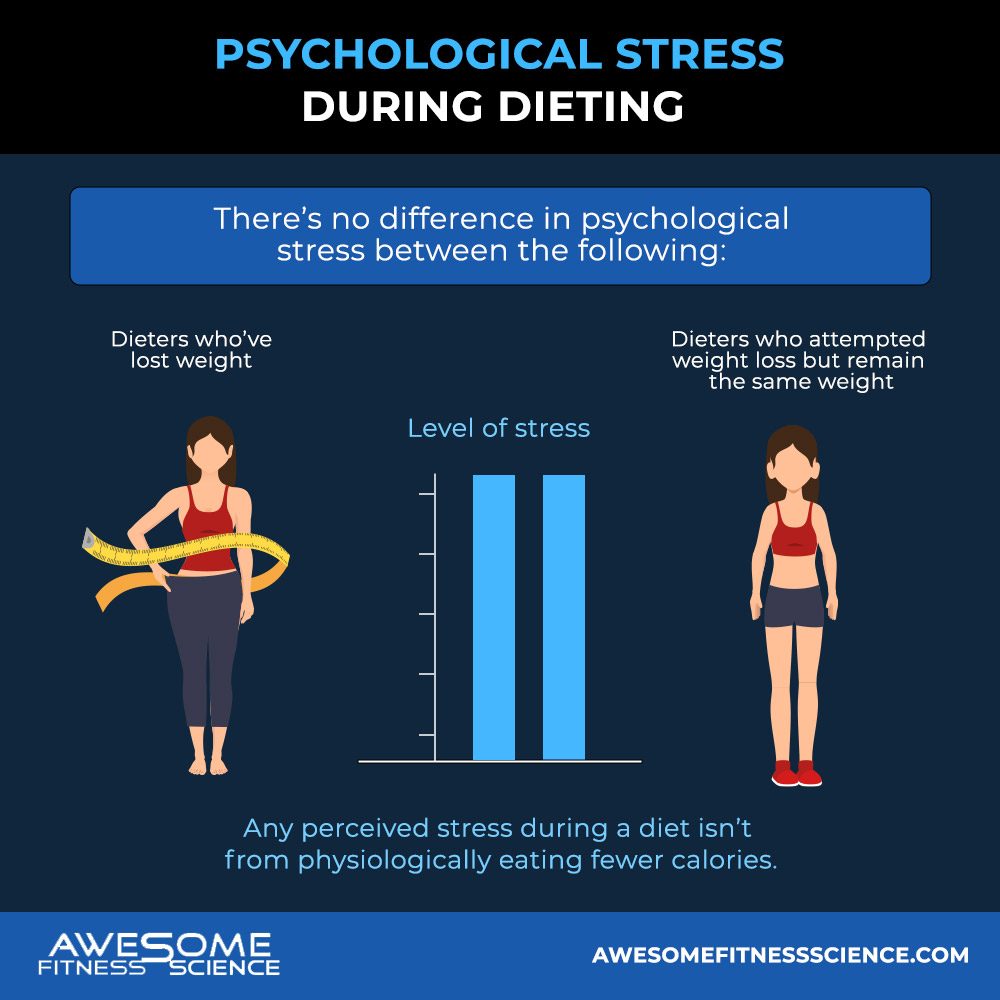

If you avoid the above by taking a refeed, you’re not fixing the root problem. You’re delaying the problem and doing so without any temporary relief. A meta-analysis of 10 controlled studies found there’s no difference in psychological stress between dieters who’ve lost weight or dieters who attempted weight loss, but remained at maintenance (29). In other words, any perceived stress during a diet isn’t from physiologically eating fewer calories.

It’s simply from knowing you’re on a diet because humans associate dieting as unpleasant. Nonetheless, if the thought of dieting is going to be uncomfortable anyways, you might as well reap the most results for your efforts and keep going.

Anecdotally, I notice perceived stress is always outweighed by progress. Clients who insist on refeeds, don’t actually destress. They freak out because the scale is more likely to stall or trend up temporarily.

I’ve found many people think they want a refeed, but what they really want is more progress.

I do employ refeeds when clients have a big social event or holiday coming up that’s not frequent like Thanksgiving. This is simply to give them the option of enjoying life more, not to enhance the diet itself in any way.

I tell them, you won’t lose progress by taking a refeed and I encourage you to take it guilt-free if it’s worth it for you. But if you change your mind, you can still stick to the dieting calories, make a bit more progress, and further lock in the habits necessary for the future.

Again, this is infrequent. If you justified a refeed for every social event or stressful day, you’d be yoyo-ing your calories all week and never accumulate meaningful weight loss.

On another note, refeeds are extremely useful for physique competitors to refuel glycogen and increase muscle fullness during peak week (37). This is a noteworthy use of refeeds, but unfortunately contest prep related circumstances don’t apply to most people.

Because of everything mentioned, refeeds are generally overrated. The physiological benefits are clearly unsupported and the little psychological benefits don’t always outweigh the drawbacks.

1.

DA;, Chin-Chance. “Twenty-Four-Hour Leptin Levels

Respond to Cumulative Short-Term Energy Imbalance and Predict Subsequent

Intake.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, U.S.

National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10946866/.

2.

Kolaczynski . “Response of Leptin to Short-Term and

Prolonged Overfeeding in Humans.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and

Metabolism, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8923877/.

3.

Deighton. “A Single Day of Mixed-Macronutrient

Overfeeding Does Not Elicit Compensatory Appetite or Energy Intake Responses

but Exaggerates Postprandial Lipaemia during the next Day in Healthy Young

Men.” The British Journal of Nutrition, U.S. National Library of

Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30696504/.

4.

Kolaczynski . “Responses of Leptin to Short-Term

Fasting and Refeeding in Humans: a Link with Ketogenesis but Not Ketones

Themselves.” Diabetes, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8866554/.

5.

Jebb, S A, et al. “Variability of Appetite Control

Mechanisms in Response to 9 Weeks of Progressive Overfeeding in Humans.” Nature

News, Nature Publishing Group, 14 Feb. 2006,

www.nature.com/articles/0803194.

6.

Dirlewanger. “Effects of Short-Term Carbohydrate or Fat

Overfeeding on Energy Expenditure and Plasma Leptin Concentrations in Healthy

Female Subjects.” International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic

Disorders : Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity,

U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11126336/.

7.

Hulmi, Juha J, et al. “The Effects of Intensive Weight

Reduction on Body Composition and Serum Hormones in Female Fitness

Competitors.” Frontiers in Physiology, Frontiers Media S.A., 10 Jan.

2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5222856/.

8.

McDevitt, Regina M, et al. “Macronutrient Disposal

during Controlled Overfeeding with Glucose, Fructose, Sucrose, or Fat in Lean

and Obese Women.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 1 Aug. 2000,

academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/72/2/369/4729415.

9.

RL;, Rosenbaum. “Long-Term Persistence of Adaptive

Thermogenesis in Subjects Who Have Maintained a Reduced Body Weight.” The

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18842775/.

10. T;,

Nakamura. “Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Reveals Acutely Elevated Plasma

Cortisol Following Fasting but Not Less Severe Calorie Restriction.” Stress

(Amsterdam, Netherlands), U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26586092/.

11. Rossow

. “Natural Bodybuilding Competition Preparation and Recovery: a 12-Month Case

Study.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, U.S.

National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23412685/.

12. Johnstone.

“Influence of Short-Term Dietary Weight Loss on Cortisol Secretion and

Metabolism in Obese Men.” European Journal of Endocrinology, U.S.

National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14763916/.

13. M;,

Rask. “Cortisol Metabolism after Weight Loss: Associations with 11 β-HSD Type 1

and Markers of Obesity in Women.” Clinical Endocrinology, U.S. National

Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22233384/.

14. Tam,

Charmaine S, et al. “No Effect of Caloric Restriction on Salivary Cortisol

Levels in Overweight Men and Women.” NCBI, HHS Public Access,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3946997/.

15. Abraham,

S B, et al. “Cortisol, Obesity, and the Metabolic Syndrome: a Cross-Sectional

Study of Obese Subjects and Review of the Literature.” Obesity (Silver

Spring, Md.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, Jan. 2013,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3602916/.

16. Herzog

. “Effects of Daytime Food Intake on Memory Consolidation during Sleep or Sleep

Deprivation.” PloS One, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22768272/.

17. Wadden

. “Less Food, Less Hunger: Reports of Appetite and Symptoms in a Controlled

Study of a Protein-Sparing Modified Fast.” International Journal of Obesity,

U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3667060/.

18. RD;,

Devitt. “Effects of Food Unit Size and Energy Density on Intake in Humans.” Appetite,

U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15010185/.

19. Martin

. “Examination of Cognitive Function during Six Months of Calorie Restriction:

Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial.” Rejuvenation Research, U.S.

National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17518698/.

20. Lieberman,

Harris R, et al. “Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Test of 2 d of Calorie

Deprivation: Effects on Cognition, Activity, Sleep, and Interstitial Glucose

Concentrations.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 1 Sept. 2008,

academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/88/3/667/4754441.

21. Shukitt-Hale,

Barbara, et al. “Effects of 30 Days of Undernutrition on Reaction Time, Moods,

and Symptoms.” Physiology & Behavior, Elsevier, 15 Apr. 1999,

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031938497002369.

22. Yasin,

Wardah Mohd, et al. “Does Religious Fasting Affect Cognitive Performance?” Nutrition

& Food Science, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 6 Sept. 2013,

www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/NFS-06-2012-0069/full/html.

23. PJ;,

Green. “Lack of Effect of Short-Term Fasting on Cognitive Function.” Journal

of Psychiatric Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7473300/.

24. Solianik,

Rima, and Artūras Sujeta. “Two-Day Fasting Evokes Stress, but Does Not Affect

Mood, Brain Activity, Cognitive, Psychomotor, and Motor Performance in

Overweight Women.” Behavioural Brain Research, Elsevier, 31 Oct. 2017,

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0166432817314286.

25. A;,

Solianik. “Effect of 48 h Fasting on Autonomic Function, Brain Activity,

Cognition, and Mood in Amateur Weight Lifters.” BioMed Research

International, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28025637/.

26. LK;,

Pardue. “Case Study: Unfavorable But Transient Physiological Changes During

Contest Preparation in a Drug-Free Male Bodybuilder.” International Journal

of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, U.S. National Library of

Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28770669/.

27. RJ;,

Attuquayefio. “A Systematic Review of Longer-Term Dietary Interventions on

Human Cognitive Function: Emerging Patterns and Future Directions.” Appetite,

U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26299715/.

28. Karl,

J. Philip, et al. “Transient Decrements in Mood during Energy Deficit Are

Independent of Dietary Protein-to-Carbohydrate Ratio.” Physiology &

Behavior, Elsevier, 3 Dec. 2014,

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031938414006015.

29. Booth.

“Diet-Induced Weight Loss Has No Effect on Psychological Stress in Overweight and

Obese Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Nutrients,

U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29757978/.

30. Campbell,

Bill I., et al. “Intermittent Energy Restriction Attenuates the Loss of Fat

Free Mass in Resistance Trained Individuals. A Randomized Controlled Trial.” MDPI,

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 8 Mar. 2020,

www.mdpi.com/2411-5142/5/1/19.

31. Peos,

Jackson, et al. “Contrary to the Conclusions Stated in the Paper, Only Dry

Fat-Free Mass Was Different between Groups upon Reanalysis. Comment on:

‘Intermittent Energy Restriction Attenuates the Loss of Fat-Free Mass in

Resistance Trained Individuals. A Randomized Controlled Trial.’” MDPI,

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 20 Nov. 2020,

www.mdpi.com/2411-5142/5/4/85.

32. Pasiakos

. “Acute Energy Deprivation Affects Skeletal Muscle Protein Synthesis and

Associated Intracellular Signaling Proteins in Physically Active Adults.” The

Journal of Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20164371/.

33. Areta

. “Reduced Resting Skeletal Muscle Protein Synthesis Is Rescued by Resistance

Exercise and Protein Ingestion Following Short-Term Energy Deficit.” American

Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism, U.S. National Library

of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24595305/.

34. Carbone.

“Effects of Short-Term Energy Deficit on Muscle Protein Breakdown and

Intramuscular Proteolysis in Normal-Weight Young Adults.” Applied

Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition Et

Metabolisme, U.S. National Library of Medicine,

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24945715/.

35. Murphy,

Chaise, and Karsten Koehler. “Caloric Restriction Induces Anabolic Resistance

to Resistance Exercise.” European Journal of Applied Physiology,

Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 31 Mar. 2020,

link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-020-04354-0.

36. Cara B. Ebbeling, PhD. “Effects of Dietary Composition on Energy Expenditure During Weight-Loss Maintenance.” JAMA, JAMA Network, 27 June 2012, jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1199154.

37. Wilson

M. A. M. de Moraes, Fernando N. de Almeida. “Carbohydrate Loading Practice in

Bodybuilders: Effects on Muscle Thickness, Photo Silhouette Scores, Mood States

and Gastrointestinal Symptoms.” Journal of Sports Science and Medicine,

19 Nov. 2019, www.jssm.org/hf.php?id=jssm-18-772.xml

Grab my free checklist on how to defeat your worst food cravings

Detoxing is the latest buzzword and everyone thinks they need to detox. However, nobody knows what they’re detoxing from, what detoxing accomplishes, and to how to go about it.

You ready to go from a mere peasant who can’t stop eating to a satiated almighty weight loss emperor?

Cholesterol was once thought of as a dangerous artery clogging nutrient. Fortunately, research shows cholesterol is not the enemy we once thought it was.