1. Validate User, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/71/1/130/4729298.

2. Buhl . “Unexplained Disturbance in Body Weight Regulation: Diagnostic Outcome Assessed by Doubly Labeled Water and Body Composition Analyses in Obese Patients Reporting Low Energy Intakes.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7594141/.

3. Chandon, Pierre, and Brian Wansink. “Obesity and the Consumption Underestimation Bias.”

4. Mahabir . “Calorie Intake Misreporting by Diet Record and Food Frequency Questionnaire Compared to Doubly Labeled Water among Postmenopausal Women.” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16391574/.

5. J;, Macdiarmid. “Assessing Dietary Intake: Who, What and Why of under-Reporting.” Nutrition Research Reviews, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19094249/.

6. Lichtman . “Discrepancy between Self-Reported and Actual Caloric Intake and Exercise in Obese Subjects.” The New England Journal of Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1454084/.

7. Champagne . “Energy Intake and Energy Expenditure: A Controlled Study Comparing Dietitians and Non-Dietitians.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12396160/.

8. Wise, Roy A. “Brain Reward Circuitry: Insights from Unsensed Incentives.” Neuron, Cell Press, 17 Oct. 2002, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0896627302009650.

9. White. “Development and Validation of the Food-Craving Inventory.” Obesity Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11836456/.

10. Schwedhelm, Carolina, et al. “Meal Analysis for Understanding Eating Behavior: Meal- and Participant-Specific Predictors for the Variance in Energy and Macronutrient Intake.” Nutrition Journal, BioMed Central, 25 Apr. 2019, nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12937-019-0440-8.

11. Archer, Edward, et al. “The Inadmissibility of What We Eat in America and Nhanes Dietary Data in Nutrition and Obesity Research and the Scientific Formulation of National Dietary Guidelines.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, U.S. National Library of Medicine, July 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4527547/.

12. BM;, Nielsen. “Patterns and Trends in Food Portion Sizes, 1977-1998.” JAMA, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12533124/.

13. Robinson, Eric, et al. “(Over)Eating out at Major UK Restaurant Chains: Observational Study of Energy Content of Main Meals.” The BMJ, British Medical Journal Publishing Group, 12 Dec. 2018, www.bmj.com/content/363/bmj.k4982.

14. Zuraikat, Faris M, et al. “Increasing the Size of Portion Options Affects Intake but Not Portion Selection at a Meal.” Appetite, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Mar. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4728005/.

15. Raghoebar, Sanne, et al. “Served Portion Sizes Affect Later Food Intake through Social Consumption Norms.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 20 Nov. 2019, www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/12/2845.

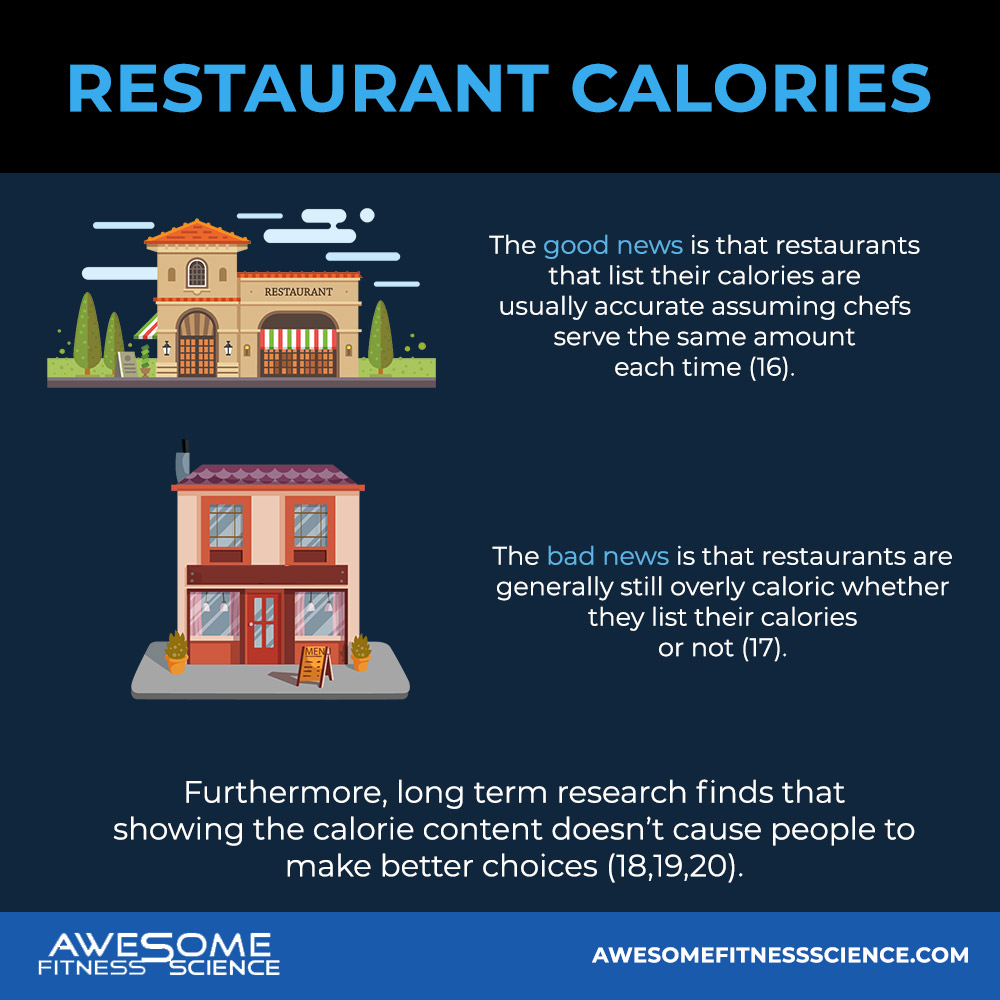

16. Lorien, PhD. “Accuracy of Stated Energy Contents of Restaurant Foods.” JAMA, JAMA Network, 20 July 2011, jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1104116.

17. Lorien , PhD. “Energy Content of Restaurant Foods.” JAMA Internal Medicine, JAMA Network, 22 July 2013, jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/1687518.

18. Roberto, Christina A, et al. “Evaluating the Impact of Menu Labeling on Food Choices and Intake.” American Journal of Public Health, American Public Health Association, Feb. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2804627/.

19. Kiszko, Kamila M, et al. “The Influence of Calorie Labeling on Food Orders and Consumption: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Community Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4209007/.

20. Petimar, Joshua, et al. “Estimating the Effect of Calorie Menu Labeling on Calories Purchased in a Large Restaurant Franchise in the Southern United States: Quasi-Experimental Study.” The BMJ, British Medical Journal Publishing Group, 30 Oct. 2019, www.bmj.com/content/367/bmj.l5837.

21. Racette, Susan B, et al. “Influence of Weekend Lifestyle Patterns on Body Weight.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, Aug. 2008, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3740215/.

22. Jahns . “Diet Quality Is Lower and Energy Intake Is Higher on Weekends Compared with Weekdays in Midlife Women: A 1-Year Cohort Study.” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28254199/.

23. Validate User, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/110/4/842/5552759?login=true.

24. JM;, Stroebele-Benschop. “Environmental Strategies to Promote Food Intake in Older Adults: A Narrative Review.” Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27153250/.

25. Gustafson, Christopher R., et al. “Exercise and the Timing of Snack Choice: Healthy Snack Choice Is Reduced in the Post-Exercise State.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 7 Dec. 2018, www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/12/1941.

26. Proserpio, Cristina, et al. “Ambient Odor Exposure Affects Food Intake and Sensory Specific Appetite in Obese Women.” Frontiers in Psychology, Frontiers Media S.A., 15 Jan. 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6340985/.

27. Robinson . “Eating Attentively: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Food Intake Memory and Awareness on Eating.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23446890/.

28. Blass . “On the Road to Obesity: Television Viewing Increases Intake of High-Density Foods.” Physiology & Behavior, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16822530/.

29. SB;, McCrory. “Dietary (Sensory) Variety and Energy Balance.” Physiology & Behavior, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22728429/.

30. Epstein . “Long-Term Habituation to Food in Obese and Nonobese Women.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21593492/.

31. Validate User, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/113/3/716/6123941.

32. Ogden, Jane. “Distraction, Restrained Eating and Disinhibition: An Experimental Study of Food Intake and the Impact of ‘Eating on the Go’.” Journal of Health Psychology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26296575/.